The Roman Catholic Diocese of Peoria, Ill., has already constructed a museum in honor of Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, a native son whose Emmy-winning television show during the 1950s and '60s brought Catholicism to the American living room. It has documented several potential miracles by him and compiled a dossier on his good works for the Vatican.

It has drawn up blueprints for an elaborate shrine in its main cathedral to house his tomb and sketched out an entire devotional campus it hopes to complete when its campaign to have him declared the first U.S.-born male saint succeeds.

There has been just one snag in the diocese's carefully laid veneration plans: the matter of Sheen's body.

Since his death at 84 in 1979, his remains have been sealed in a white marble crypt at St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York, the city where he spent much of his life. And though the Peoria diocese says it was promised the remains, Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan, who considers Sheen something of a personal hero, has refused to part with them, citing the wishes of the archbishop and his family.

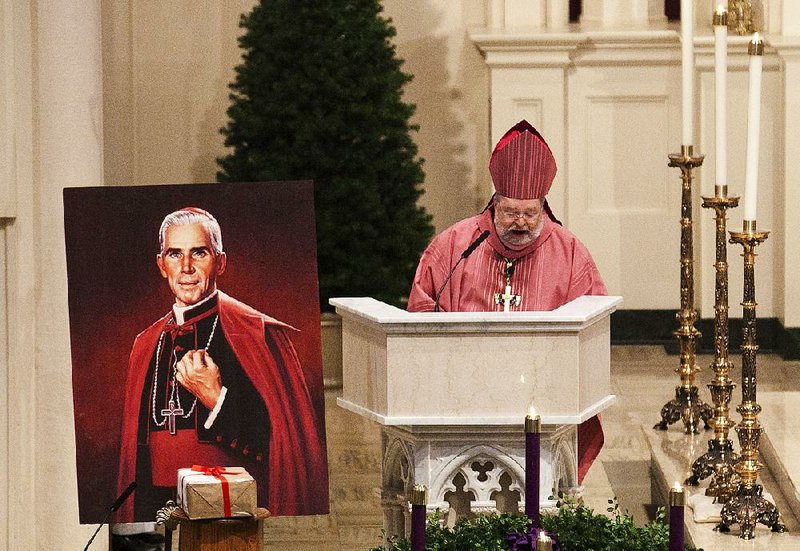

Now the dispute over Sheen's corpse has brought a halt to his rise to sainthood, just as he appeared close to beatification, the final stage before canonization. Bishop Daniel R. Jenky, Peoria's leader, announced this month that the process had been suspended because New York would not release the body.

To be sure, disputes over remains of saints are nothing new in the Roman Catholic Church, and in the past the resolution has sometimes been to divide the body. St. Catherine of Siena is enshrined in Rome, but her head is revered in a basilica in Siena, Italy. St. Francis Xavier, the 16th-century missionary, is entombed in Goa, India, but his right arm is in Rome, in a reliquary at the Church of the Gesu.

That type of compromise does not seem to be a possibility this time. Dolan's latest offer to Jenky was that he could have bone fragments and other relics from Sheen's coffin, but not the body itself. And certainly no limbs.

The very public tug of war over the body of Sheen has shocked many Catholics, in part because it seems like something that belongs in another era.

"We should have moved out of the 14th century by now," said Joan Sheen Cunningham of Yonkers, a niece of the archbishop and, at 87, his oldest living relative. "I would have thought so." She wants the body to remain where it is.

"All this focus on the body, the body," Cunningham said last week. "It's forgetting what the purpose of the whole thing is. To keep someone from coming beatified over this, I think, is wrong."

Sheen was best known for reaching up to 30 million viewers each week as the charismatic host of the DuMont (and later ABC) television show Life Is Worth Living, which ran from 1951 to 1957, and later The Bishop Sheen Program from 1961-'68. At a time when American Catholics were still struggling for acceptance in the United States, he became a hero to many, including Dolan, then a young boy.

To honor his legacy, Dolan used archdiocesan funds to create the Sheen Center, a performing arts center in Manhattan that opened this year. And he has repeatedly said the body should remain in New York. "You know, Bishop Sheen only spent a few years in Peoria," he said in 2009 when the issue started brewing. "And he loved New York."

Sheen had bought a plot at Calvary Cemetery in Queens, intending to be buried there, Cunningham said. But just after his death at age 84, Cardinal Terence Cooke offered the space in the crypt. Being buried in his home diocese of Peoria, Cunningham said, "is just not what my uncle wanted."

Jenky said he believed that Sheen would now feel differently.

In 2002, Cardinal Edward M. Egan, then the archbishop of New York, declined to sponsor Sheen's cause for sainthood, an expensive and time-consuming process. So the Peoria diocese, in which Sheen was ordained, stepped up. Over the past dozen years, it has spent countless hours on the cause, collecting 15,000 pages of testimony about Sheen's virtues, seeking out miracles and, yes, designing a tomb.

According to Peoria diocesan officials, Egan twice assured the diocese, in 2002 and 2004, that the archbishop's remains would be transferred at the appropriate time. Back then, they said, even Cunningham was supportive, and his memorial foundation furnished a copy of a 2005 letter she wrote to the Vatican as proof. But in 2009, Dolan, who was then an archbishop, became the head of the New York diocese, and things appeared to change.

"Bishop Jenky would never have begun this if he weren't personally assured that the tomb of Fulton Sheen would come home to Peoria," said Monsignor Stanley Deptula, vice chancellor of the Peoria diocese.

In 2010, Jenky briefly tabled his campaign for Sheen's sainthood, saying in a news release that the New York archdiocese had "made it clear that it is not likely that they will ever transfer the remains." Pressured by devotees, however, Jenky soon resumed work on the cause.

In 2011, Dolan posted on his blog a letter to Peoria that stated that his own study of the matter had revealed "that there was in fact no evidence of such a verbal promise."

Meanwhile, Sheen drew ever closer to sainthood. In 2012, Pope Benedict XVI declared the archbishop "venerable." In March, a panel of Vatican medical experts certified a miracle attributable to him. Jenky speculated that Sheen could be beatified as early as 2015. After that, only one more certified miracle would be required before sainthood.

Suddenly, the matter became urgent: By canon law, the body should be exhumed and authenticated before beatification, and relics -- bone fragments and other physical remains -- taken for the purpose of veneration. Jenky wanted that process to take place in Peoria.

In June, however, he received a letter from the New York archdiocese saying it "would never allow" the exhumation of the body, the securing of relics or the transfer of the body, a statement from Peoria said. And on Sept. 3, Jenky announced "with immense sadness" that the cause had been suspended.

New York had been on the verge of offering a compromise. Cunningham said she met with Dolan on Sept. 2 and agreed to permit her uncle's body to be exhumed and relics collected for the shrine in Peoria.

"I think the cardinal was worried that maybe that Bishop Jenky would cut off a hand or an arm or something," Cunningham said.

Neither Jenky nor Dolan would comment directly on the matter, but the public statement from New York indicated one way forward: If Peoria would not reconsider its position, it said, "the Archdiocese of New York would welcome the opportunity to assume responsibility for the cause."

Religion on 09/20/2014