One of the differences between art and science is that, given the proper controls, science insists on the repeatability of experience, while art argues all experience is relative and peculiar. Romance lives in our margins for error -- what the lover of vinyl records perceives as authentic warmth is really distortion and cyclic wow and flutter. Most of us would be embarrassed in a blind taste test comparing our "favorite" wines or bourbons with generic examples. Science can be a boorish dinner party guest.

It is not difficult to make an alcoholic beverage. Fermentation is a natural process that occurs when organic materials containing sugar, such as fruit, decompose. All you need is a bit of the specialized fungi we call yeast. The Sumerians were brewing beer in 3200 B.C.; birds can become buzzed (or dangerously drunk) on fermented berries. Once you figure out that water has a higher boiling point than ethyl alcohol, you can start to get fancy distilling hooch.

Making booze is science.

Selling it is art.

A few months ago, a liquor merchant candidly (if anonymously) admitted that she thought the recent craze for moonshine was silly. She could understand why the producers were pushing it -- the profit margins on unaged white whiskey are likely to be higher than with products that might be racked for decades -- but she didn't credit consumer-side allegations of flavorful nuance in the various potions. They might as well be drinking grain alcohol, she said.

As one who regularly finds fine distinctions in things that to the disinterested eye might seem homogeneous, I'm sensitive to speculations about possibly naked emperors. There are reasons to prefer some clarets to others. Still, having tried a few of these "legal moonshines" -- corn liquor, white lightning, white dog, mountain dew, what have you -- I'm inclined to go along with her.

To begin with, the term "legal moonshine" is oxymoronic. If it's sold in a liquor store it's not a "moonshine." By definition moonshine is unregulated, untaxed and illegal. While there's no legal requirement for whiskey to be aged, it traditionally has been. The clear stuff in the bottle with the faux naive label you've picked up at the liquor store isn't whiskey but a kind of pre-whiskey. Moonshine is to whiskey what a hunk of marble is to Michelangelo's David. If I bothered to argue about label puffery, I'd say anything labeled "Moonshine Whiskey" is probably neither.

But fashion is what it is, and so we get glossy lifestyle magazines offering us articles on "the best" (and most expensive) legal 'shines. We haul out the Mason jars and the ghost of Junior Johnson (the NASCAR legend and bootlegger whose name adorns a product line) and play like we're hillbillies. Most of the appeal lies in marketing and the perceived romance of illegal hooch.

That's not to say they all taste the same (they don't; some are jarringly neutral, others flirt with agave, and some have an aromatic, almost fruity edge) or that they don't have a certain utility. Most of the moonshines I've tried would serve as an adequate vodka substitute. In my personal bar you'll find a bottle of Rock Town's Arkansas Lightning, along with their Apple Pie variation; in the refrigerator we keep some Ole Smoky Tennessee Cherries (maraschino cherries soaked in Ole Smoky moonshine). But I don't sit around and sip the stuff. There's a reason we age bourbon in wooden barrels.

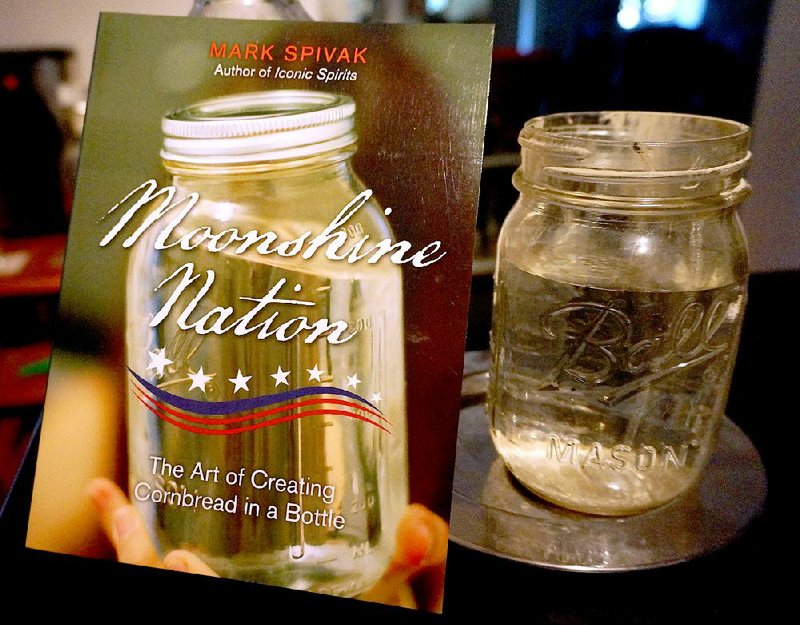

Given my general skepticism, you might understand why I regarded booze blogger Mark Spivak's new book Moonshine Nation: The Art of Creating Cornbread in a Bottle (Globe Pequot/Lyons, $16.95) with some suspicion. I thought it might be a promotional brief for the spirit or more Southern myth mongering. Instead it's a clear-eyed history of moonshining in America that is especially good in its analysis of the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791-94. It's best received as a valuable and readable collection of stories about the people who made the whiskey and the unintended consequences of Prohibition, finished off with a directory of distillers.

The second half concentrates on present-day manufacturers and includes a fairly balanced portrait of the late Marvin "Popcorn" Sutton. The problematic Sutton was a walking tourist attraction who was, in author Max Watman's words, "more about performance and presentation than liquor." In his later years, Sutton made a career of his reputation as one of the last moonshiners -- he spoke at folk festivals and, in the 1990s, set up a still for the Museum of Appalachia in Clinton, Tenn.

For years, whatever actual bootlegging Sutton engaged in was tolerated. He was convicted five times, but each conviction resulted in probation. But in March 2008, he was arrested by undercover officers after he told them he had 900 gallons of moonshine ready to sell. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 18 months in prison. On March 16, 2009, three days before he was to report to prison, he hooked up a hose to the exhaust pipe of his Ford Fairlane (his "two-jug car," because he'd traded two jugs of whiskey for it) and killed himself with carbon monoxide.

Like almost everybody else, I'm susceptible to a good story. But I think that most moonshiners were probably closer to modern-day meth dealers than the romantic outlaws we make them out to be. They made their hooch as cheaply and quickly as they could, and they were only as careful as they thought they had to be. I would wager that almost any of the so-called moonshine you can pick up at your local liquor shop is superior in every way to what was typically brewed up in the hollers.

That doesn't make it whiskey. And while Sutton was probably more carny barker than criminal, most moonshiners were more like Heisenberg than da Vinci.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 09/21/2014