Comic books can be a super way to learn.

Take it from Superman. Here he is, for example, in Action Comics (1961), lecturing Supergirl and young readers in general on the importance of education:

"Whenever I visit a strange civilization," the big guy says, "I always get full information at one of their libraries first."

Rocket forward, and today's Man of Steel probably could find the information he needs in the form that suits him best -- a comic book.

Today's comics tackle subjects as diverse as civil rights, biography and science. Some are children's reading; many are for teens. Words and pictures can be as deep as a college text.

"In the last five years, I've seen a lot of serious journalism going on in comics," says Michael Ray Taylor, professor of communication at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia. Taylor and faculty colleagues Randy Duncan and David Stoddard are writing a textbook guide to the trend, Creating Comics as Journalism, Memoir and Nonfiction.

Cartoons as teaching tools go back at least to World War II, Taylor notes, "when you had Disney characters teaching soldiers how to clean their rifles."

The next decade, the 1950s, pitched the funnies out of the classroom. Worried parents blamed the sometimes horrific comic books of those days for corrupting young minds. Out they went, the ghouls and gangsters -- and almost the entire comics industry.

Whoosh! How things have changed:

• Common Core teaching standards cite graphic novels (book-length comics) among types of stories appropriate for classroom reading in grades six through 12.

• Comic-book distributor Diamond Books cites more than 80 graphic novels for use as "legitimate teaching tools" in line with Common Core.

Books escalate by grade level, from Power Lunch: First Course (Oni Press) in first grade to The Comic Book History of Comics (IDW Publishing) for grades 10 and higher. The list is available at diamondcomics.com under the heading, "Educators and Librarians."

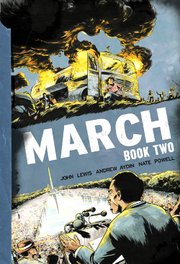

• March: Book One (Top Shelf) is the civil rights memoir of U.S. Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., told as a graphic novel. North Little Rock native Nate Powell illustrates the script by

Lewis' policy adviser, Andrew Aydin.

The 2013 New York Times best-seller won the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award, and is among the Young Adult Library Services Association's "Top 10 Graphic Novels for Teens."

"Thousands of kids have read it this summer alone as part of summer reading plans," Aydin says. "You can fantasize, but you never think your fantasies will come true." This time, for this book, amazements happened.

A CONGRESSMAN'S COMIC

Aydin tells how March came to be, describing himself as a "comic book fan all my life." In 2008, working for Lewis, he mentioned that he planned to attend a comics convention during his vacation.

Others of the congressman's staff "laughed at me," he says. But not Lewis. From the back of the room in a deep voice, he remembers, Lewis said: "There was a comic book during the movement, and it was incredibly influential."

That title was Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, a 1957 10-cent comic. It concludes with King's advice: "Make sure you can face any opposition without hitting back, or running away, or hating."

Aydin suggested a comic about Lewis' own experience as a civil rights leader. Lewis approved, even agreeing to help write it. But in his typical way, Aydin says, "he made it a challenge."

The comic would be Aydin's off-hours project and it "lived on the coffee table of my house for nights and weekends."

Going into the project, Aydin knew how a great comic should read, not how to write one. He learned from how-to books by cartoonists Will Eisner (Comics and Sequential Art), and Scott McCloud (Understanding Comics).

Driven by Lewis' story, enlivened by Powell's art, the book became, as publisher Top Shelf describes it, "a vivid first-hand account."

With March: Book Two in progress toward a trilogy, Aydin says, he has been hearing from other lawmakers suddenly interested in being comic-book figures. "I've definitely had other lawmakers ask me how to do it," he says, "or ask me if I would help them do it.

"But I don't think anyone else's story has the power of Congressman Lewis'."

WHY SO SERIOUS?

Other comics use the splash of bright colors and bold lines to teach difficult subjects. New from No Starch Press, The Incredible Plate Tectonics Comic is by writer Kanani K.M. Lee, associate professor in the department of geology and geophysics at Yale University in Connecticut, with her husband, comic-book artist Adam Wallenta.

The comic's boy hero, Geo, imagines himself a superhero on a rocket-powered surfboard, able to swoosh 200 million years back in the planet's history. He arrives just in time to see that "Earth is going through a dramatic change." His robot dog, Rocky, is handy to explain the upheaval.

The continents -- "well, actually, the tectonic plates," the talking dog corrects himself -- pieces of the earth's shell are on the move.

"I was looking for a way to do a fun but meaningful outreach program that would mesh well with my research on the deep earth," Lee says. The idea was also compatible with a National Science Foundation grant she received for career development.

Wallenta took on the illustration job aside from his regular work as a comic-book colorist, whose subjects have included The X-Men.

"'I've been reading comics since I was about 7 years old, and there has always been a message involved," he says. "Many comic-book characters such as Spider-Man, The Fantastic Four, The Hulk, their alter egos are often scientists and highly educated people. The stories always contained language, science and concepts that were over my head and inspired me to research.

"I knew when I set out to make my own comics, I wanted to inspire young readers in the same way, " he says. The trick is a combination of "wonder and real-world science and education."

An earlier version of the book was offered free to teachers in New Haven, Conn., and is available free online at adventuresofgeo.com.

No Starch Press also has comics about website building, human anatomy, statistics, physics, the periodic table of elements -- "and now earth science," spokesman Mackenzie Dolginow says.

Geo's next adventure will take him to the center of Earth.

IT'S CLOBBERIN' TIME

Lifebuoy soap-sponsored "School of 5" comics aim at teaching millions of children in poor countries how to "save the world from evil germs" by washing their hands.

Meanwhile, educators pay serious attention to comics in the teaching profession's magazines and journals, as evidenced by these comments:

• "Comic strips are the perfect vehicle for learning and practicing language." -- Education Digest

• "Some of the best artists and writers working today are focused on this new and exciting format." -- Educational Leadership

• "Emerging research suggests [comics] may serve an educational use by encouraging children to read and introducing more complicated or high-level concepts." -- Journal of Health Studies

For another example of the increasing scope of the form, Taylor points to artist Dan Archer's nonfiction comics, which are online at archcomix.com. Archer defines his "comics journalism" as comics that aim "to inform and (dare I say) educate the reader," the intent of his reports on human rights violations.

This may be the next direction of reporting at length, Taylor says.

"I don't think long-form journalism is going away," he says. "But what is going away is the magazines that used to carry it."

Next? -- maybe online comics with maps and hyperlinks, animation, how-to graphics, show-and-tell.

"People used to say there never could be anything serious on television," the professor says. "There could never be anything serious in the movies."

In fact, he admits, there was a time he would have said the idea of comics for education sounded "a little squirrelly."

But a smart thing happened on the way to the funny pages.

Family on 09/24/2014