Mental health experts say that it was aggression -- not just depression -- that would have driven 27-year-old Andreas Lubitz to deliberately crash a Germanwings airliner into a mountainside, the co-pilot breathing evenly as passengers screamed and the plane's frantic captain pounded helplessly on the cockpit door.

Unless investigators recognize the toxic role of aggression and hostility in some patients' depression, they say, such troubled individuals will continue to elude detection -- to the public's peril.

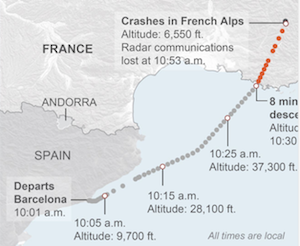

Lubitz's history of depression, acknowledged by his employer in the days after the March 24 crash of the Airbus A320 with 150 people aboard, left many mental health professionals in the United States openly skeptical that Lubitz's psychological troubles stopped there. In the parade of garden-variety depressives who march into their offices, psychiatrists and psychologists often hear about the physical symptoms of mental distress -- sleep problems, stomachaches, even changes in vision. They routinely see sadness, guilt and hostility.

But a murder-suicide on this scale, they said, requires an explanation that goes beyond a simple diagnosis of depression.

"We need to stop talking as if this was a suicidal guy with access to an airplane," said Dr. Jeff Victoroff, a neuropsychiatrist at the University of Southern California's Keck School of Medicine and a leading researcher on aggression. "This was a murderous guy who probably had elements of a mood disorder and personality disorders."

"People who have depression alone are much, much more likely to bring harm to themselves alone," said forensic psychiatrist Dr. Steven Pitt, who consults with the Phoenix Police Department and conducted the Columbine Psychiatric Autopsy Project after the 1999 high school shootings in Colorado. "There has to be a maladaptive character defect, a character disorder here."

In recent days, reports of Lubitz's behavior in the weeks before the crash have hinted at some of the emotional distortions and likely mental illness that may have motivated him, said several forensic psychiatrists in interviews. While a full diagnosis cannot come from such bits of information, they are piecing together Lubitz's history of depression, possibly heightened by an unraveling romantic relationship and a perceived threat -- vision problems -- to his career.

In the preliminary accounts of Lubitz's life before he killed himself and 149 others, they see a highly unstable and emotionally sensitive young adult who probably felt his world was coming apart.

A well-designed personality inventory alone -- the kind of detailed questionnaire used by many employers -- would probably have flagged traits that diverged dramatically from the standard profile of a pilot: emotionally stable, resilient and self-disciplined. To have declared Lubitz "100 percent fit to fly," as Lufthansa CEO Carsten Spohr initially did, "was like pronouncing the Titanic unsinkable just after it hit the bottom of the ocean," Victoroff said.

The German newspaper Bild reported last week that Lubitz, despite fearing for his job, purchased two expensive cars in recent weeks. In the paper's account, Lubitz tried to give one of the two cars to Kathrin Goldbach, his girlfriend of seven years, in a bid to cement their failing relationship. Another German news report cited a former girlfriend saying Lubitz told her, "One day, I will do something that will change the whole system, and then all will know my name and remember it."

Such details offer evidence of what mental health professionals call a "disordered personality" coming undone. With the right tools, they said, the danger he posed might have been identified and stopped.

"This is a mass-murder/suicide," said Victoroff. "It appears to have been premeditated. And it was preventable."

Those willing to kill others when taking their own lives are generally men and are extremely hostile, psychiatrists say. Most have a history of mental anguish that may extend back to childhood.

In personality assessments and in sessions with mental health professionals, they also tend to exhibit callousness and narcissism. They often have an inflated view of themselves and their powers, and a powerful sense of entitlement.

In manifestoes and personal accounts they leave behind, their sense of victimhood and their vengeful drive to punish their tormentors are common themes, experts say. Yet they wish to be remembered for a grand and even glorious accomplishment.

Experts acknowledge that predicting whether an individual is on a path toward suicide, violent behavior -- or both -- is anything but simple. And efforts to do so are likely to draw resistance from employee, privacy and civil liberties advocates. Victoroff, for his part, contends that such tools should be used where public safety is at stake.

"We don't want to pull people out of their careers for minor personal quirks, or even having had an episode of depression," said Victoroff. "But the combination of problems this guy was exhibiting was too much."

A Section on 04/06/2015