On Wednesday, Congress will present the Congressional Gold Medal to a group of 80 American Army Air Force volunteer fliers who helped change the course of World War II in the Pacific. The medal, one of the highest civilian awards in the U.S., is awarded to those who have performed a signal service that has an impact on American history and culture and is likely to be recognized as a major accomplishment in the recipient's field long afterward.

The group, which became known as the Doolittle Tokyo Raiders for its daring bombing raid on Japan on April 18, 1942, was led by then-Lt. Col. James H. "Jimmy"

Doolittle, a brilliant aviator who set several speed and endurance records as a stunt and racing pilot before giving up the sport and focusing on commercial and military aeronautical pursuits.

My father, David J. Thatcher, was a gunner and flight engineer on the Raid and is one of only two surviving members of that historic mission 73 years ago this week.

On Monday, a new book about the raid, Target Tokyo, will be released. Written by noted military author James M. Scott, it's a comprehensive account covering events leading up to the Doolittle Raid, the Raid itself, and its aftermath. Scott spent years researching the book by scouring archives on four continents and offers a significant amount of information not previously published.

Scott will make a presentation on the book, followed by a book signing, at 6 p.m. April 22 at the Clinton School of Public Service in Little Rock.

The Doolittle Raid took place four months after the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor by the Imperial Japanese Navy. In those four months, the world as Americans had known it had crumbled. A significant portion of the U.S. Pacific Fleet was sent to the bottom of Pearl Harbor and the Japanese seemed unstoppable, winning victory after victory in the Far East. Morale in the U.S. was sinking by the day, and Americans were desperate for any morsel of good news.

Charged with striking back at Japan for the attack on Pearl Harbor, Doolittle and his band of gritty volunteers would accomplish what seemed nearly impossible. America needed a victory and some heroes to look up to, and Doolittle and his Raiders would deliver splendidly, striking back at the Japanese with a blow to their homeland and shattering their belief in their own invincibility. There hadn't been a successful invasion or attack on their homeland in the 2,600 preceding years.

The Raiders, along with thousands of other supporting military personnel aboard the carrier USS Hornet, were part of a 16-ship task force that departed San Francisco Bay in early April 1942. While streaming toward Japan, the armada was spotted by Japanese patrol boats before the planned departure of the 80 Raiders in 16 B-25 twin-engine bombers.

Their exposure forced the Raiders to take off 12 hours earlier and approximately 150 nautical miles farther from Japan than planned. The weather conditions were miserable with rain, 20-knot gusting winds and huge waves crashing over the bow of the aircraft carrier. Yet, despite knowing they were likely embarking on a suicide mission, the 80 volunteer fliers never wavered.

One after another, each B-25 lumbered down the deck of the carrier and took off. Following each other in single file and flying by dead reckoning just above the wave tops to avoid detection, they reached Japan at midday and fanned out to drop four 500-pound bombs each on military and industrial targets in Tokyo, Yokohama, Kobe and Nagoya.

Although some of the B-25s encountered anti-aircraft fire and enemy fighters, none were shot down or severely damaged. Fifteen of the 16 planes then proceeded southwest along the southern coast of Japan and across the East China Sea toward eastern China, where recovery bases supposedly awaited them. The remaining B-25s, low on fuel, headed for Russia, which was closer.

Night was approaching, fuel was running out, and the weather was rapidly deteriorating during the Raiders' flight to China. The crews realized they would not be able to reach their intended bases, leaving them the option of either bailing out over eastern China or crash-landing along the Chinese coast. When the dust settled, 15 planes had been destroyed in crashes. The crew that flew to Russia landed near Vladivostok, where their B-25 was confiscated and the crew interned until escaping in May 1943.

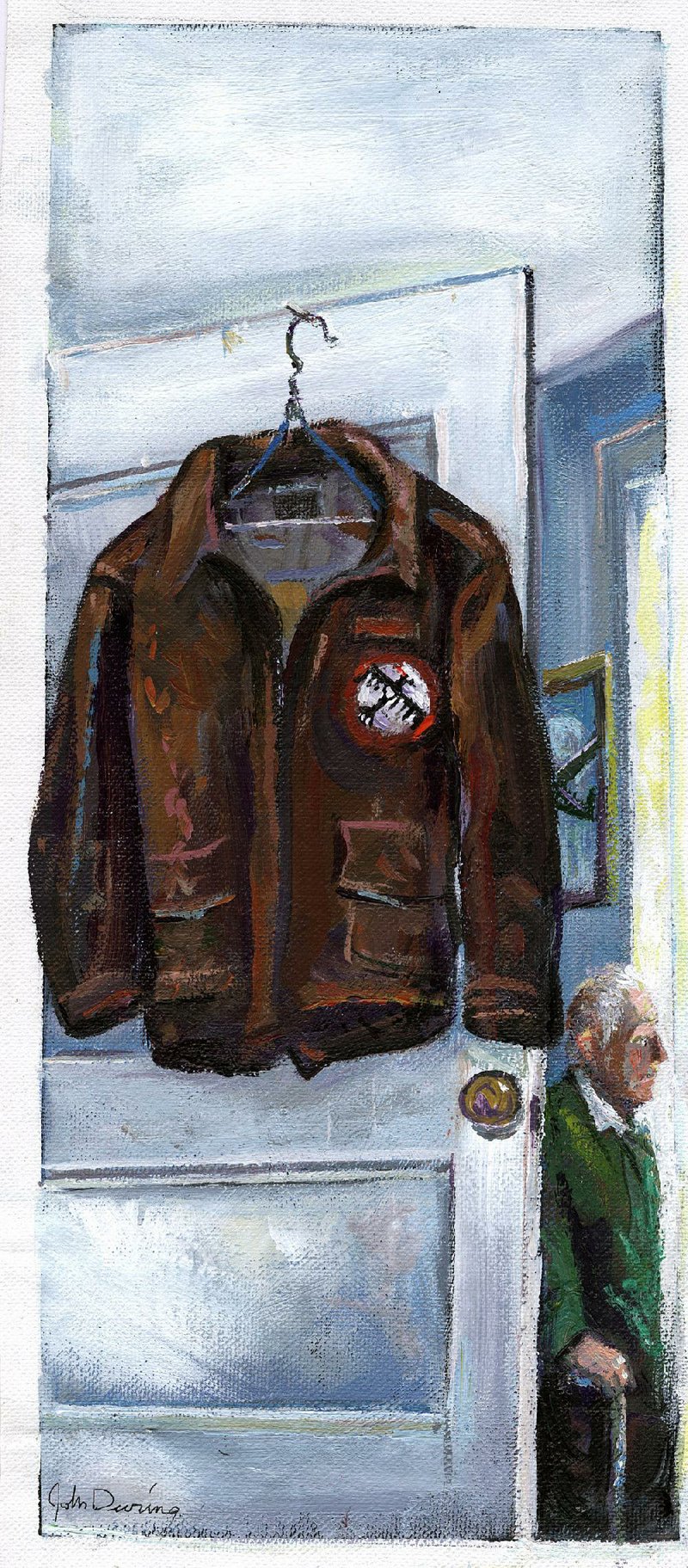

My father was the tail gunner and engineer on Crew No. 7, "The Ruptured Duck," which was piloted by Lt. Ted Lawson, who later wrote Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, the famous book on the raid. Lawson tried to land the plane on a beach in darkness and heavy rain, but instead crashed in the surf after hitting a wave at approximately 140 miles per hour, causing the plane to flip over. All the members of the crew were seriously injured except for Dad, who was briefly knocked out in the crash but suffered only a bump to his head.

After regaining consciousness and making it to shore, Dad saved the lives of his crew by gathering them on the beach, administering first aid and making contact with some friendly Chinese guerrillas who had come upon them. He convinced the guerrillas to take the crew to safety in inland China. Over the next few days, the crew barely escaped capture by Japanese patrols searching for the Raiders. For his efforts, Dad received the Silver Star, the nation's third highest medal for heroism.

Three Raiders were killed during attempts to land in China. Eight were captured by the Japanese; three were subsequently executed and a fourth starved to death in prison. Following the Doolittle Raid, most of the B-25 crews that came down in China eventually made it to safety with the help of Chinese civilians and flew other wartime missions. But the Chinese paid dearly as the Japanese killed an estimated 250,000 civilians in retaliation for their assistance to the Raiders.

Compared to the devastating B-29 fire-bombing attacks against Japan later in the war, the Doolittle Raid did little material damage. Nevertheless, when news of the raid was released, American morale soared. The raid also had a strategic impact on the war. The Japanese military recalled many units back to the home islands for defense, where they remained while battles raged throughout the Pacific.

More importantly, the Doolittle Raid provoked Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of the raid on Pearl Harbor, to attempt to grab Midway Island, an ill-fated expedition in June 1942 that resulted in the loss of four fleet carriers, many sailors and a number of highly trained air crews from which the Imperial Japanese Navy never recovered.

Besides being the first offensive air action against the Japanese home islands, the Doolittle Raid was the first combat mission in which the AAF and the U.S. Navy teamed up in a full-scale operation against the enemy. The Raiders were also the first to fly land-based bombers from a carrier deck on a combat mission and the first to use new cruise-control techniques in attacking a distant target.

The incendiary bombs they carried were forerunners of those used later in the war. The special camera equipment specified by Doolittle to record the bomb hits was later adopted by the AAF. And the after-action crew recommendations concerning armament, tactics and survival equipment were used as a basis for other improvements.

Jeff Thatcher is a professional communicator and longtime resident of Little Rock.

Editorial on 04/12/2015