Joyce Bolte lost her oldest son 20 years ago in a bomb blast that shook the nation. She finds solace in the memorials that keep his memory alive.

Ron Asbill lost a piece of himself after experiencing the bombing's aftermath.

"There's no closure," he said. "It happened."

Asbill, who now lives in Siloam Springs, was home in Mannford, Okla., when he felt the ground quiver at 9:02 a.m. April 19, 1995.

A few minutes later, Bolte got word while working in Wal-Mart's transportation department in Bentonville that there had been an explosion at the federal building in Oklahoma City.

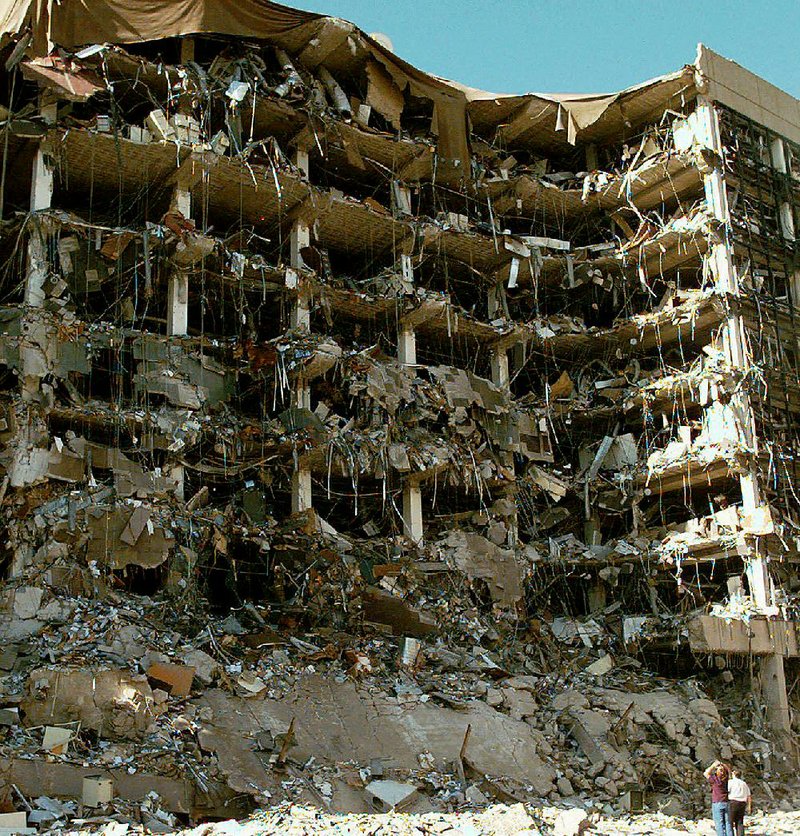

Timothy McVeigh detonated a truck bomb in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, killing 168 people and injuring another 684, according to a 1998 Oklahoma Department of Health report.

Bolte's son, Mark, was working in the building.

Asbill was an emergency medical technician, and he received a call to help 30 minutes after the bomb exploded. Not knowing exactly where to go, he followed the ugly black plume of smoke downtown, ending up at Presbyterian Hospital, a mile northeast of the heavily damaged building.

"Chaos ... No one knew what was going on," he recalled. "There were wounded people everywhere. There's people in the waiting room, there's people in the parking lot, there's people sitting on the curbs."

Asbill went with a surgical-extraction team to the bomb site, but an Army engineer stopped them because of a possible gas leak. The team gave the engineer amputation tools to deliver to a doctor for a person whose leg was pinned in rubble.

The air was hot and smelled like burning rubber, with dust and paper blowing everywhere, he said. Bricks and glass littered the streets. Debris and damage spread for blocks in every direction. The area was filled with destroyed cars. Sirens sounded, people screamed.

Asbill looked down a street and saw a police officer crying on the back of his patrol car.

Back at the hospital, a man asked Asbill to help unload black nylon body bags from a truck.

"I grabbed it, and I was expecting it to be heavy. When I picked it up, everything went to the middle," Asbill said, pausing to regain composure. "So we carried those into a dark room off the side of the street there. Makeshift morgue. Seven kids."

Those were seven of the 19 children killed in the blast. The Murrah building had a day care on the second floor. Officials tried to identify the children, but "I didn't see one that was whole," Asbill said.

He left the hospital about 4 p.m., around the time Arkansas Highway and Transportation Department officials called Bolte's family and said they believed her son was in an area hospital. Mark Bolte was a civil engineer and environmental specialist for the Federal Highway Administration in Oklahoma City.

The Oklahoma Transportation Department called Bolte's home later in the evening to confirm her son was missing. Nearly half of the 550 people who worked in the building were unaccounted for at the end of the first day, according to news reports.

Mark Bolte had been home in Bentonville three days earlier for Easter.

"When he got ready to leave, I said, 'We really need to get over and see your apartment.' And he said, 'Yeah, you do.' Boy, I didn't expect to see it that way," Joyce Bolte recalled.

Bolte, her husband, Don, and younger son, Matt, went to Oklahoma City and stayed in Mark's apartment for two weeks while rescue and recovery teams searched for him.

Mark Bolte's body was the last recovered before the building was demolished May 23. His identity was confirmed by dental records. He was 28.

He was found in one piece, Joyce Bolte said.

Three more bodies, including that of Virginia Thompson, were recovered after the building was demolished, according to news reports. Thompson was the sister of Ruth Ellen Quinnett of Bella Vista.

Bolte recalled the overwhelming community support the family members received when they returned to Bentonville. Ribbons covered their yard and were hung around Bentonville High School and on trees downtown.

A fund established to help with expenses became the inspiration for the Mark Bolte Memorial Engineering Scholarship, which provides $500 to a graduating Bentonville High School student to study engineering. There were 31 applicants this year, Bolte said.

The government invited families of victims to McVeigh's trial and execution. Bolte went with a friend to a part of the trial. She recalls his blank stare and lack of remorse.

"I was angry at God, and sometimes I still am," she said. "Timothy McVeigh, after I saw him, I put him out of my mind ... I would rather spend my life remembering Mark than hating Timothy McVeigh. I seldom ever think of him."

Bolte didn't attend McVeigh's execution in 2001. Going wasn't going to fix anything, she said.

Bolte's healing over the years stems largely from the way people remember her son, she said: trees planted in his name, a bench created and dedicated in front of the family's church, an overpass in a small Texas town named after him, photos of him and some of his belongings in the Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum.

His kindness, tenderness and willingness to help anyone is what people talk about when they talk about him, Bolte said.

"Mark will live a long time after I'm gone."

Spring and Christmas remain difficult for Bolte.

"I'm not as happy as I usually am," she said. "I've caught myself the past week or so crying at the drop of a hat, and I don't know why. I try to tell myself that it's not because of that, but maybe it is -- I don't know."

Spring brings anxiety for Asbill, triggered by something as simple as dogwood trees, because the white flowers remind him of the petals that blew in the breeze the day of the explosion.

He started experiencing nightmares about three days after the blast. Those come back this time of year, he said. They are always about the children.

"That's the first time I had ever seen somebody want to hurt other people," he said. "Being from Oklahoma, we fight on Friday night, and we're friends on Saturday morning. It was really strange that someone wanted to kill that many people."

Asbill turned in his EMT badge three months after the bombing.

He's tried twice to visit the Oklahoma City memorial. He made it inside once to where photos begin to recount the morning's tragedy.

"As soon as I saw those, every single memory just flooded to the front," he said.

Bolte has been to the memorial several times and planned to be there with a couple of family members this weekend for the 20th anniversary event, which was to include 168 seconds of silence and an address by former President Bill Clinton, who was in his first term when the attack occurred.

For her, it's a place of peace.

"They're all remembered, and they will be remembered forever," she said. "I hope people never forget what happened."

SundayMonday on 04/19/2015