BAGHDAD -- In the steamy Baghdad night, sweat poured down the faces of the Iraqi teens as they marched around a school courtyard, training for battle against the Islamic State group.

This is summer camp in Iraq, set up by the country's largest paramilitary force after Iraq's top Shiite cleric issued an edict calling on students as young as middle-school age to use their summer vacations to prepare to fight the Sunni extremists.

These young fighters could have serious implications for the U.S.-led coalition, which provides billions of dollars in military and economic aid to the Iraqi government. The Child Soldiers Prevention Act of 2008 says the United States cannot provide certain forms of military support, including foreign military financing and direct commercial sales to governments that recruit and use child soldiers or support paramilitaries or militias that do.

Hundreds of students have gone through training at the dozens of such camps run by the Popular Mobilization Forces, the government-sanctioned umbrella group of mostly Shiite militias. It is impossible to say how many went on to fight Islamic State forces, since those who do so go independently. But this summer, more than a dozen armed boys were seen by Associated Press reporters on the front line in western Anbar province, including some as young as 10.

Of about 200 cadets in a training class visited by reporters this month, about half were under the age of 18. Several said they intended to join their fathers and older brothers on the front lines.

Dressed in military fatigues, 15-year-old Asam Riad was among dozens of youths doing high-knee marches at the school, his chest puffed out to try to appear as tall as the older cadets.

"We've been called to defend the nation," the scrawny boy asserted, his voice cracking as he vowed to join the Popular Mobilization Forces. "I am not scared because my brothers are fighting alongside me."

Another 15-year-old in the class, Jaafar Osama, said he used to want to be an engineer when he grew up, but now he wants to be a fighter. His father is a volunteer fighting alongside the Shiite militias in Anbar, and his older brother is fighting in Beiji, north of Baghdad.

"God willing, when I complete my training I will join them, even if it means sacrificing my life to keep Iraq safe," he said.

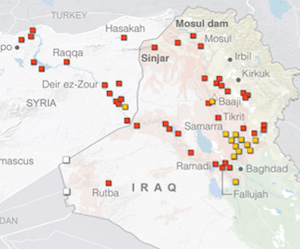

It's yet another way youngsters are being dragged into Iraq's war as the military, Shiite militias, Sunni tribes and Kurdish fighters battle to take back territory from Islamic State militants who seized much of the country's north and west last year. The Sunni extremists have aggressively enlisted children as young as 10 for combat, as suicide bombers and as executioners in their horrifying videos. Human Rights Watch said in July that Syrian Kurdish militias fighting the militants continue to deploy underage fighters.

The United States does not work directly with the Popular Mobilization Forces and has distanced itself from the Iranian-backed militias that are among the fighters under its umbrella. But the Popular Mobilization Forces receives weapons and funding from the Iraqi government and is trained by the Iraqi military, which receives its training from the United States.

When informed of the AP reporters' findings, the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad issued a statement saying the United States is "very concerned by the allegations on the use of child soldiers in Iraq among some Popular Mobilization Forces in the fight against ISIL," using an acronym for the militant group. "We have strongly condemned this practice around the world and will continue to do so."

For Iraq's Shiite majority, the war against the Islamic State group -- which views Shiites as heretics to be killed -- is a life-or-death fight for which the entire community has mobilized.

Last year, when the Islamic State took over the northern city of Mosul, stormed to the doorstep of Baghdad and threatened to destroy Shiite holy sites, Iraq's top Shiite cleric, Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, called on the public to volunteer to fight. His influence was so great that hundreds of thousands of men stepped forward to join the hastily established Popular Mobilization Forces along with some of the long-established Shiite militias, most of which receive support from Iran.

Then, on June 9, as schools let out, al-Sistani issued a new call urging young people in college, high school and even middle school to use their summer vacations to "contribute to [the country's] preservation by training to take up arms and prepare to fend off risk, if this is required."

In response, the Popular Mobilization Forces set up summer camps in predominantly Shiite neighborhoods from Baghdad to Basra. A spokesman for the group, Kareem al-Nouri, said the camps give "lessons in self-defense," and underage volunteers are expected to return to school by September, not go to the battle front.

A spokesman for the Iraqi prime minister's office echoed that. There may be "some isolated incidents" of underage fighters joining combat on their own, Saad al-Harithi said. "But there has been no instruction by the Marjaiyah [the top Shiite religious authority] or the Popular Mobilization Forces for children to join the battle."

"We are a government that frowns upon children going to war," he said.

But the line between combat training and actually joining combat is blurry, and it is weakly enforced by the Popular Mobilization Forces. Multiple militias operate under its umbrella, with fighters loyal to different leaders who often act independently.

At the training camp in a middle-class Shiite neighborhood of western Baghdad in July, the young cadets spoke openly of joining the battle -- in front of their trainers, who did nothing to contradict them.

Neighborhood youths spent their evenings in training every night during the holy month of Ramadan, which ended in mid-July, with mock exercises held every few days since then for those who wish to continue.

The boys ran through the streets practicing urban warfare techniques, since the toughest battles with the Islamic State group are likely to involve street fighting. They were taught to hold, control and aim light weapons, though they didn't fire them. They also took part in public service activities like holding blood drives and collecting food and clothing.

Earlier this summer, at one of the hottest front lines, near the Islamic State-held city of Fallujah in western Anbar province, reporters spoke to a number of young boys, some heavily armed, among the Shiite militiamen.

Baghdad natives Hussein Ali, 12, and his cousin Ali Ahsan, 14, said they joined their fathers on the battlefield after they finished their final exams. Carrying AK-47s, they paced around the Anbar desert, boasting of their resolve to liberate the predominantly Sunni province from Islamic State militants.

"It's our honor to serve our country," Hussein Ali said, adding that some of his schoolmates were also fighting. When asked if he was afraid, he smiled and said no.

The fight they are engaged in has been brutal. Islamic State atrocities are the most notorious and egregious, including mass killings of captured soldiers and civilians. But Shiite militias are said to have committed abuses as well. In February, Human Rights Watch accused individual Shiite militias under the Popular Mobilization Forces umbrella of "possible war crimes," including forcing Sunni civilians from their homes and abducting and summarily executing them.

In June, the United Nations Children's Fund called for "urgent measures" to be taken by the Iraqi government to protect children, including criminalizing the recruitment of children and "the association of children with the Popular Mobilization Forces."

Donatella Rovera, Amnesty International's senior crisis response adviser, said that if the Shiite militias are using children as fighters, "then the countries that are supporting them are in violation of the U.N. Convention" on the Rights of the Child.

"If you are supporting the Iraqi army, then by extension, you are supporting the PMF," she said.

Iraq has a long history of training underage fighters. Under Saddam Hussein, boys ages 12-17 known as "Saddam's lion cubs" would attend month-long training during summer breaks with the goal of eventually merging into the Fadayeen -- a paramilitary force loyal to Saddam's Baathist regime.

The Iraqi army restricts the age of its recruits to between 18 and 35, a policy that rights groups say is enforced. But there is no law governing the Popular Mobilization Forces. A draft law for the national guard, a force geared toward empowering Sunni tribes to police their own communities, purposely omits any age restrictions, lawmakers saying they want to open it to qualified fighters over age 35.

The U.N. convention does not ban giving military training to youths. But Jo Becker, the advocacy director of the children's rights division at Human Rights Watch, said such training puts children at risk.

"Governments like to say, 'Of course, we can recruit without putting children in harm's way,' but in a place of conflict, those landscapes blur very quickly," she said.

Once in a combat situation, children are plunged into the horrors of war, she said. "They don't have a mature sense of right and wrong, and they may commit atrocities more easily than adults."

SundayMonday on 08/02/2015