There are all kinds of ways that people come to have a writing life.

My late friend, Mississippi novelist Larry Brown, dug one out of the dirt; he looked at his options and decided he'd be better off writing books like Stephen King or Harold Robbins than cutting pulpwood or installing chain-link fences or cleaning carpets or painting houses or farming or working in a convenience store or any of the other odd jobs he took when he wasn't knocking down fires as a member of the Oxford Fire Department.

So when he was 29, he drove over to his sister's house and retrieved his wife's old Smith-Corona typewriter. He went in a room and started typing. Seven months later, he had a novel. A bad one that no one wanted to publish, but Brown kept at it. Eventually he wrote novels like Big Bad Love, Dirty Work and Joe.

On April 1, 1978, when he was 29 years old, Haruki Murakami went to a baseball game. In the bottom of the first inning, Yakult Swallows second baseman Dave Hilton swung at the first pitch and cracked a lead-off double down the left field line. And in that moment, Murakami had an epiphany.

"In that instant, for no reason and based on no grounds whatsoever, it suddenly struck me," he writes. "I could write a novel."

On his way home from the ballpark, Murakami stopped at a branch of the giant Books Kinokuniya chain and bought a sheaf of writing paper and a $5 fountain pen. That night, he started writing at his kitchen table. Four months later, he had 200 handwritten pages. He sent his only copy off to Japanese literary magazine Gunzo because it had the only competition he could find that accepted such lengthy works.

He won the Gunzo prize for best first novel. His story was published in the magazine in June 1979 and in book form -- as Hear the Wind Sing -- a month later. An English translation appeared in 1987; it was aimed primarily at English language learners and was never widely distributed in the United States. After Murakami achieved worldwide success, prices for the copies of the book exploded -- a week ago, the cheapest price I could find online was $188.

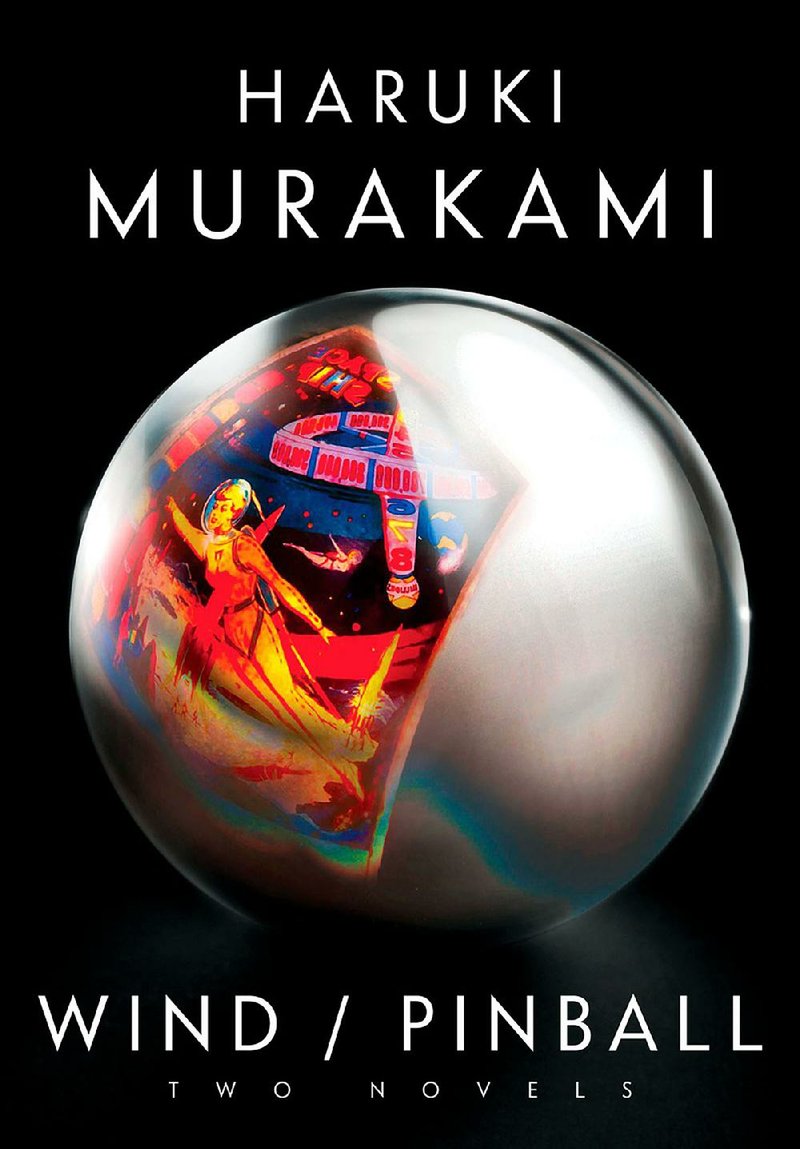

I am a Murakami fan -- I have read everything of his that I could get my hands on. But I am not obsessive- compulsive, so it wasn't until last week that I read Hear the Wind Sing, which was officially published last week, along with Murakami's second novel, Pinball, 1973 (first published in Japanese in 1980, and in English in 1985), in a single volume called Wind/Pinball (Knopf, $25.95).

The novels -- novellas, really; the entire book is only 256 pages long -- have been newly translated from Japanese by Ted Goossen, a professor of Japanese literature at Toronto's York University who previously translated Murakami's 2008 novella The Strange Library, which was published in English last year. (Presumably new translations were called for because the originals, by Alfred Birnbaum, were, as previously noted, aimed at readers learning English.) They both have that indelible sense of detachment that permeates all of Murakami's fiction, a deadpan dreaminess that fatalistically accepts all manner of remarkable goings-on.

...

While the two novels -- the first installments of Murakami's "The Rat" trilogy (the third, A Wild Sheep Chase, published in Japan in 1982, has long been available in this country) -- are a little less inclined to flights of magical realism than Murakami's later work (though in Pinball, the unnamed male narrator finds it unremarkable that he lives with two hyper-identical female twins who just show up one day), they do engage Murakami's trademark themes of alienation, ennui and the transient nature of all things.

In retrospect, the first book, a relatively simple story about a short affair the narrator, a biology student in his early 20s, had with a nine-fingered girl he found unconscious in a bar, is marked by discursions into the art and craft of writing, reflections on death and politics and music. Much of the story is set in a jazz bar not unlike the one Murakami owned at the time, where the narrator consorts with club owner J and the Rat, a disaffected dropout from a wealthy family with a talent for drinking bourbon. It is a bit like a Murakami starter kit, with all the basic themes present.

Pinball, 1973 feels like a lurch forward, a meatier and more ambitious work that incorporates the surreal elements that mark most of Murakami's work (his 1987 novel, Norwegian Wood, which propelled him to international stardom, is a realistically sketched exception). Here the Rat is less a kind of Neal Cassady figure, a brio-brimming force of nature, than a powerless, lonely man obsessed with a girl he can't have.

(Rat will later evolve into a writer in A Wild Sheep Chase and is mentioned in 1988's Dance, Dance, Dance. All these books are apparently narrated by the same unnamed character, so maybe a better rubric than "the Rat trilogy" would be the "nameless narrator tetralogy.")

Both stories are utterly delightful to read for reasons that are hard to fathom. I suspect it has as much to do with Murakami's rhythms and cadences as his choice of subject matter or the way he spins his tales. For a certain kind of reader, the most interesting pages in the book will be the introduction. Not because it once again recounts the story of how Murakami decided to become a writer -- a fanciful fable we probably ought not take literally -- but because in it he describes the process by which he wrote his first book.

He first tried writing in Japanese but found it was a dead end, that the words sounded banal and derivative to him. So he began to write in English, using the limited vocabulary that was available to him as a non-native speaker, and then translated them back into Japanese. This was his breakthrough, the discovery of a voice transposed into a slightly alien key:

"I could only write in simple, short sentences. Which meant that, however complex and numerous the thoughts running around my head, I couldn't even attempt to set them down as they came to me. The language had to be simple, my ideas expressed in an easy-to-understand way, the descriptions stripped of all extraneous fat, the form made compact, everything arranged to fit a container of limited size. The result was a rough, uncultivated kind of prose."

...

The late poet Miller Williams, like Murakami, was fluent in several languages and translated foreign writers into his native tongue. Murakami has translated Raymond Carver, John Irving, J.D. Salinger, F. Scott Fitzgerald and several other American authors into Japanese.

Williams used to say that the difference between reading and writing in his first language, as opposed to Italian, Spanish or French, was that English words were "haunted" for him; they had a patina of connotation that foreign words did not have. I believe what Murakami was doing by writing first in English was divesting his language of these ghosts, emptying the words of their freightedness. Then he could import them back into Japanese as cold, hard and heartless gems.

A couple of years ago in a story in The New Yorker, Roland Kelts quoted Jay Rubin, another of Murakami's longtime translators, as saying, "When you read ... Murakami, you're reading me, at least 95 percent of the time. ... Murakami wrote the names and locations, but the English words are mine."

Kelts wrote that while Murakami "can speak and read English with great sensitivity," the author told him he never read his own books in translation. "My books exist in their original Japanese," he quotes Murakami as saying. "That's what's most important, because that's how I wrote them."

I've written quite a bit about Murakami over the years, but there's always something elusive about his books. I always get the feeling I'm missing something, that there's a part of the novel invisible to me. Maybe that's because I haven't really read Murakami, I've only perceived his work through the filter of his translators. But maybe that filter is also part of Murakami's authorial intent -- maybe he prefers we receive his words distilled.

I'm sure he prefers a little mystery. Every artist is at least a little protective of his process. Every artist is likely to lie to you; that's what art is, a sort of lie that reveals a deeper truth. With Wind/Pinball we go back to the beginning of Murakami's writing life, to that charming anecdote about Dave Hilton's double.

Murakami has told that story many times. And I believe it, to a point. In the anecdote, Murakami is behaving precisely as one of his characters might; he is seemingly oblivious. He tells us that he sent off his only copy of the manuscript, and that he had no expectation that, if he did not win the prize, it would be returned to him.

There's more.

The day after his piece had been chosen as a finalist, he says, he went for a walk with his wife. He came across a passenger pigeon with a broken wing and, as he was rescuing it, he had another revelation: "I was going to win the prize. And I was going to become a novelist who would enjoy some degree of success."

And, had he not won the first and only literary contest he ever entered, not only would that novel been lost; he "never would have written another."

As fetching as the story is, I can't suspend my disbelief. Brown collected hundreds of rejection slips before finally finding a publisher. Murakami may have been luckier, but had he not been, I prefer to believe he would also have kept trying.

...

Given more time and space, these are the books I'd be writing about: Former British poet laureate Andrew Motion's rip-roaring The New World (Crown, $25), his second sequel to Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island after 2012's Silver; Don Winslow's The Cartel (Knopf, $27.95); Filip Bondy's The Pine Tar Game (Scribner, $25), a readable history of one the most bizarre moments in baseball history when umpires nullified a home run by the Kansas City Royals' George Brett based on an obscure rule limiting how high pine tar could extend on a bat; former Hunter S. Thompson editorial assistant Cheryl Della Pietra's Gonzo Girl (Simon & Schuster, $25), which Karen Martin recently reviewed on my blog, blooddirtangels.com; and Saban (Simon & Schuster, $27), Monte Burke's biography of the divisive University of Alabama football coach Lou Saban that I intend to write about before the Southeastern Conference lid-lifter.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 08/09/2015