Flaking a bite onto his fork, John McQuaid took in the sight of the whole rockfish before him, its fishiness visible beneath a chili-dotted red curry sauce.

"This is an example of something I would never have eaten as a child," he said, noting the way the Thai lunch stared back at him from a fish-shaped plate. "I just thought it was disgusting."

His 13-year-old daughter, Hannah, would certainly agree. She prefers "mostly white foods," choosing pasta and cheese over just about anything else (although she did recently allow a green condiment, pesto, to be added to the list).

Her brother Matthew, 15, is picky in his own way, but on the other end of the spectrum: He loves piquant and spicy foods like Sichuan shrimp, and he even joined his father in sampling the world's hottest pepper. But he won't eat fast food or hamburgers, leaving a family-on-the-go with few options.

How did McQuaid's children's tastes come to be in such vehement opposition? Did the two inherit different genes? Were they exposed to different foods in the womb?

Why and how do our palates evolve, anyway?

For McQuaid, a Pulitzer Prize-winning science journalist, answering those ques

tions soon had him fully immersed in the study of taste, a sense that, compared with sight or smell, had long been ignored by scientists despite popular preoccupations with it. The answers turned into his second book, Tasty: The Art and Science of What We Eat (Scribner).

Published in January, Tasty tells the story of the evolution of flavor, from the first bite by a single-celled organism to the proliferation of flavor combinations that today's chefs are only beginning to unearth. In it, McQuaid wonders how our flavor preferences, rooted in genetics and shaped over time by a shared culture, remain as unique as our fingerprints.

His search for understanding walks readers through an enthralling survey of taste.

ON THE TONGUE

It starts with a close-up view of the "bizarre, Lovecraftian-looking" receptors on our taste buds that distinguish sweet from salty, bitter from sour, and umami, the pleasantly savory note we get from cooked meat or mushrooms that was added to the list in 2001.

Tasty tells us why George H.W. Bush banned the bitter brassica broccoli from the White House in the early 1990s, how we came to drink cow's milk despite a natural intolerance (by letting it go bad first), and how all five of the senses feed our brains an all-encompassing message of flavor.

Though the book will probably draw a following of the food-obsessed, McQuaid, 53, is not one of them. His children's food preferences have for years left him and his wife, Trish Clay, eating at chain restaurants on vacation and serving as short-order cooks at their home in Silver Spring, Md.

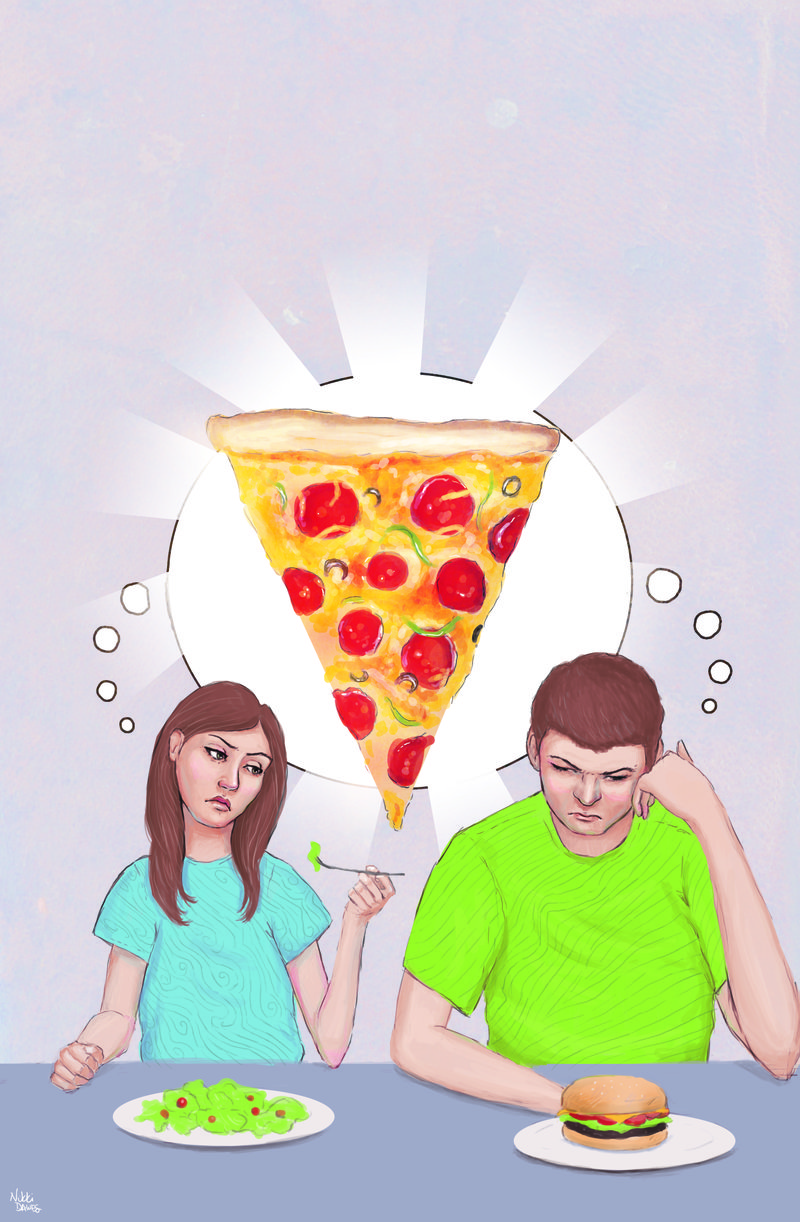

Feeding their children, McQuaid writes, had become "a Rubik's Cube challenge; only pizza satisfied everyone."

FIRE AND FERMENTATION

McQuaid tackles the subject with a journalist's curiosity, delivering his findings through a narrative that starts with the prehistoric underpinnings of flavor. Although he might lose some gourmet on his trek through the Cambrian period, McQuaid picks them back up when relatives of Homo sapiens have their first communal cookout.

The application of fire to food, as you might have noted in your own kitchen, radically alters the flavor equation. Those first flames quickly turned raw meat into flavorful processing power, allowing the brain that guzzles a quarter of an adult's daily calories to develop. Getting more calories faster freed early humans to do something other than chew all day, and it opened up a new world of taste.

Around the campfire, McQuaid writes, "taste, smell, sight, sound, and touch coalesced into our own flavor sense -- a new type of perception that helped give birth to the human form and to culture."

The book goes on to survey the biggest advancements in flavor over the ages, stopping to focus on a few. It touches on the advent of fermentation, which rivals fire in its ability to cultivate our boldest and most beloved flavors. (Distilling the subject to a single chapter was difficult, McQuaid said.) Another section is devoted to the science behind our dangerous love affair with sugar and the race to find healthful substitutes.

Researching the book took McQuaid to Momofuku's test kitchen in Brooklyn, N.Y. (He was sworn to secrecy about its location to prevent groupies from stopping by.) He also went to Iceland for a bite of foul-smelling hakarl, a fermented shark flesh that depicts how "entire nations can come to love things that repel outsiders."

When he started writing Tasty three years ago, McQuaid wondered why no one had delved into the evolution of flavor before. One could argue, after all, that we've never been more infatuated with what we put into our mouths.

But, a few pages in, he realized the challenge of crafting a digestible story that draws from so many scientific and sociological disciplines. "I was trying to cross-reference things that aren't usually cross-referenced," he said, which left him asking questions such as, "If you're a proto-human being and you're roasting a shank of meat for the first time, what was that experience like?"

Through his research he learned that he is far from a "supertaster." He took the bitter taste test and is actually a "nontaster" who can hardly tell fine wines apart. His son is also a nontaster.

REAPER

"It's not that spicy," McQuaid said of his pla chu chee (fried fish in red curry) Thai lunch. "It's hot, but it's not super hot." The dish had appeared on the menu next to three peppers, signifying the highest heat level, but he was unfazed.

As recessive-gene nontasters, McQuaid and his son have elevated thresholds for chile heat. Naturally, they plumbed those heights by tasting the world's hottest pepper, the Carolina Reaper, for a chapter in the book devoted to some humans' mysterious hankering for the hot stuff.

"The burning spread over my tongue and around my mouth and became overwhelming," McQuaid writes of the painful, yet somehow pleasant, experience he shared with his son. "Voices around me receded as I slouched in my chair."

Matthew tried to stop the burn by chasing it with buttered bread and, when that didn't work, ranch dressing followed by a lime.

The capsaicin chemical that bludgeoned their heat receptors causes pain but then blocks it. That explains, in part, why spice-seekers keep coming back for more.

McQuaid brought a small bottle of the hot sauce made from those peppers to lunch, in case, after reading his words, I was still masochistic enough to try it; I wasn't.

He also brought a few purple miraculin pills, made from a tongue-tricking ingredient he first tried while "flavor tripping" at a Chicago restaurant. Made from miracle berries, the substance blocks some sweet receptors while making strong acids taste sweet. (These I gladly tried, and, sure enough, they made a lemon fished from a water glass taste like chiffon pie.)

LIMITS OF SCIENCE

Did all his experiments lead McQuaid to a solution for his family's dinnertime quandary?

Not exactly.

He still hasn't found a week's worth of menu items upon which his family members can agree, although he does understand their differences at a more microscopic level.

"It goes back to a sense of flavor being like a snowflake or a fingerprint; it is unique, yet it develops over the course of your lifetime," he reasoned.

For now, his kids' tastes "continue to diverge."

McQuaid's book ends by looking to a future in which scientists and chefs are only beginning to unleash the possibilities of flavor, using technology to pair ingredients that are chemically alike (oysters and kiwi, chocolate and caviar) but uncommonly combined into new dishes.

After marrying such improbable flavors, perhaps they'll find a way to unite his picky eaters around a common meal.

Or maybe they don't need to. Pizza, after all, has been around for a thousand years.

Family on 02/18/2015