When your father dies

take notes

somewhere inside.

-- Miller Williams, "Let Me Tell You"

The above line comes from a poem in which Arkansas poet Miller Williams urged us to make use of whatever was at hand, including the dying of a friend.

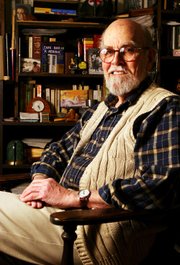

Williams was my beloved friend. He died in Fayetteville on Jan. 1. He was 84 years old.

I was asked by his widow to write an obituary. This is my attempt to honor that request, and to make use of Miller's dying the best I can.

I think of obituaries as an act of journalism designed to put the community on notice, a quasi-official inverted-pyramid story to be read over one's morning coffee. An obituary provides facts and, maybe, if there is space and time enough, the reporter might share an anecdote or a quote from someone who knew the deceased, designed to give a tender glimpse into the person's character.

I wish I could turn out a deft and compact synopsis and appreciation of the great man's life, and maybe leave you with a bemused smile, but I am struggling to invert Miller's pyramid.

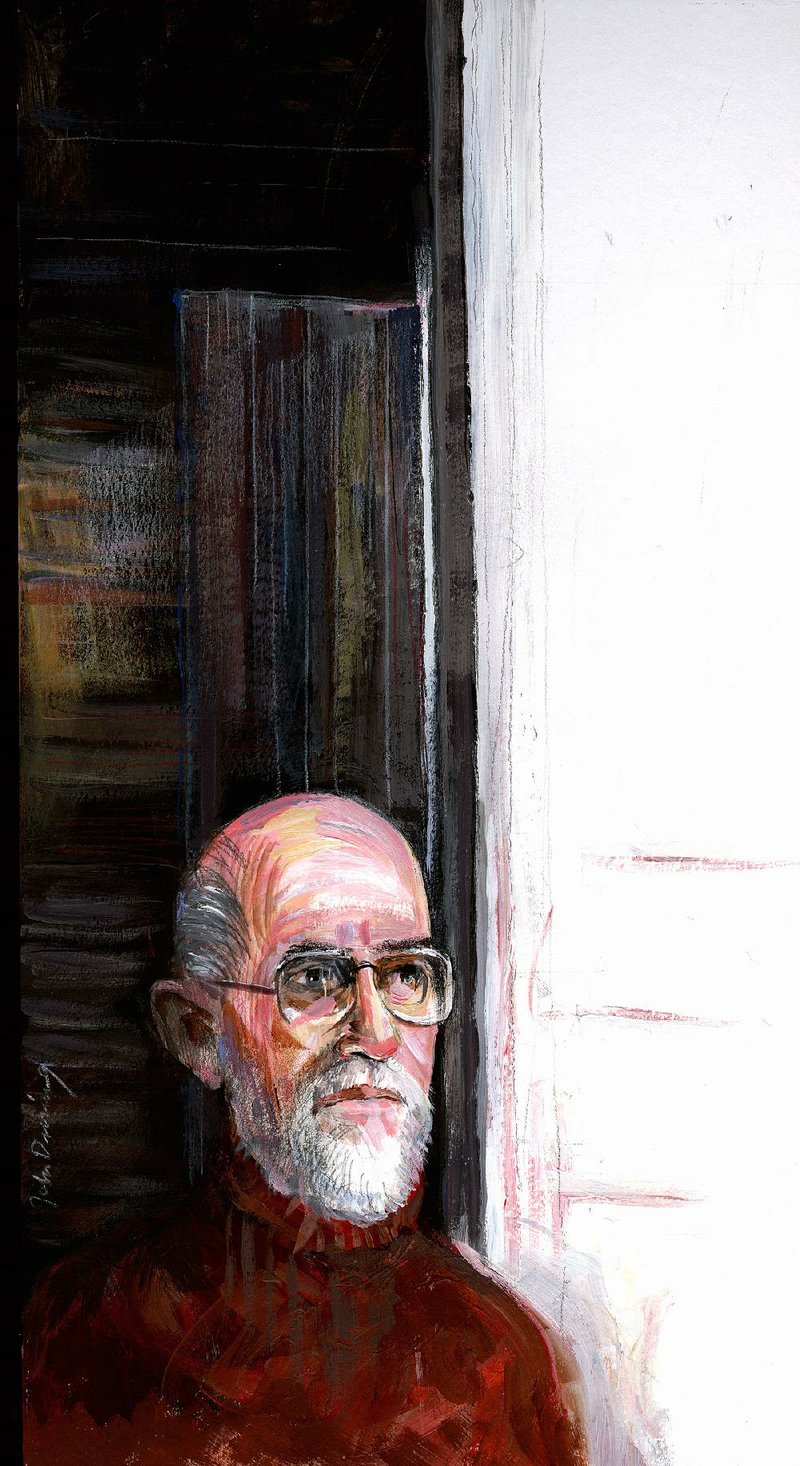

More than this black thicket of text, Miller Williams deserves an edifice -- or a city. Some monument that might survive the blighted centuries to come.

He might disagree with that and remind me of Shelley's "Ozymandias." Miller was a scientist; he understood the odds favored existential ice over rapturous fire and, while we might be delighted by whatever prizes we collect in this life, they are ultimately vanities. He had a great sense of humor about this. Here's the entirety of his poem "My Wife Reads the Paper at Breakfast on the Birthday of the Scottish Poet":

Poet Burns to Be Honored, the headline read.

She put it down. "They found you out," she said.

The first few lines of the conventional obituary would note that he read his occasional poem "Of History and Hope" at President Bill Clinton's second inauguration in 1997. That Miller was the co-founder of the University of Arkansas Press, which he directed for 17 years, and of the university's Master of Fine Arts in literary translation program and was instrumental in the shaping of its MFA in creative writing program. It would note that he was married to Jordan, his wife since 1969; that he was the father of three children -- singer-songwriter Lucinda Williams, Robert and Karyn -- and a grandfather and a great-grandfather.

Over the years he published more than 40 books, collections of poetry, translations of foreign poets' work, textbooks and even -- with James A. McPherson -- a history of America's railroads. Maybe the obit would

mention his 1952 meeting with Hank Williams in Lake Charles, La., an occasion on which the singer advised the poet to "drink beer."

After he told me that story, I teasingly referred to Miller as "The Hank Williams of American Poetry" every time I mentioned him in print. It pleased him, but there is truth in it. Miller's plainsong had the same tough honesty as Hank's voice; the same uncommon sensitivity to the extraordinary experience available to ordinary people. On the other hand, I don't remember Miller as much of a beer drinker -- his especial fondness was for Woodbridge Chardonnay, which we poured from 1.5-liter bottles.

...

Miller was born in Hoxie, and was one of six children. His father, E.B., was a Methodist preacher, an early integrationist who sought to organize sharecroppers in the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union. The Williams family moved about Arkansas frequently -- to Fort Smith, Booneville, Paragould and Russellville. Miller began writing early and found himself especially drawn to poetry. But after he entered Hendrix College in Conway, a counselor put him on a different path.

"A psychological evaluation indicated I had no verbal aptitude," he said. "I was told I'd embarrass myself and my family."

So he went into science. He studied hard and well and ended up doing graduate work in zoology, teaching high school and college biology. He married young, had a family and went to work selling appliances for Sears and college textbooks out of his car's trunk. But he always wrote poetry.

In 1950, teaching biology at Millsaps College in Jackson, Miss., Miller hosted a poetry show on television (can you imagine such a thing these days?) and had poems published in The New York Times. He thought he might live out his life as a scientist/poet, balancing vocation and avocation like pediatrician William Carlos Williams or novelist Walker Percy, who was trained as a physician.

But in 1961 he met John Ciardi, the poet who would become his friend and mentor. Ciardi invited Miller to the prestigious Bread Loaf Writers' Conference in Vermont. There Williams met Robert Frost and discovered a kind of community of poets he had suspected existed but had never before encountered. The next year, Miller joined the faculty of Louisiana State University at Baton Rouge -- as an English professor.

His poems remain shot through with science. His training has lent his work a kind of epistemological skepticism -- a distrust of certitude that nonetheless acknowledges the role faith plays in human pursuits. His 2007 poem "After All These Years of Prayer and Pi R Square" illuminates his synthesis of these two seemingly antithetical paths of intellectual striving:

How sweet a confusion that science, that creed of the creature,

that earthly philosophy of numbers in motion,

distrusted by rabbi, sheik, and preacher

who have clothed its nakedness in flame,

should quietly introduce us to the notion

of something weightless within us wanting a name

...

Any conventional obituary of Miller would necessarily include a representative, though probably not inclusive, list of the honors he was accorded, including the Prix de Rome for Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Harvard's Amy Lowell Traveling Scholarship for poetry, the New York Arts Fund Award for Significant Contribution to American Letters, the Henry Bellaman Poetry Prize, the Charity Randall Citation for Contribution to Poetry as a Spoken Art, the John William Corrington Award for Literary Excellence and the Academy Award for Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He has been named Socio Benemerito dell'Associazione of the Centro Romanesco Trilussa in Rome. In 1990, he won the prestigious Poet's Prize.

But you don't measure a man by the prizes he wins, for there are all sorts of reasons people win (and fail to win) prizes. People who live in Arkansas know their accomplishments are by and large discounted by the people who live in our country's coastal cultural centers and by their own neighbors, who are given to wondering why, if you're so good, why are you still here?

A good obit writer would note Miller lived all over the world and spoke a half-dozen languages or more (including Esperanto), yet he spent most of his life in the state where he was born. There were prizes that Miller did not win, and I asked him about them. One of the things that people who live in Arkansas know is that there is a price to be paid for living here.

"I think of myself as an Arkansawyer, but not an Arkansas poet," Miller used to say. "I would rather live in Arkansas than win any prize on earth."

Miller could say this because he had the chance to travel and a not inconsiderable part of the world wound up passing through his orbit. He served as visiting professor of U.S. literature at the University of Chile and Fulbright professor of American studies at the University of Mexico. For seven years he was a member of the poetry faculty at the Bread Loaf Writers' Conference. He represented the U.S. State Department on reading and lecturing tours through Latin America, Europe, the Middle East and the Far East. He published stories, translations, poems and critical essays in most of the seminal journals and mass circulation magazines in the United States and many in Canada, Latin America and Europe. His poems have been translated into many languages; he translated Pablo Neruda into English.

...

The walls of Miller's Fayetteville home were splashed with photographs and paintings, with a story attached to every one. He had a lot of friends, many of them celebrated.

He rode on tour buses with Johnny Cash and Tom T. Hall. During the civil rights era, as marchers were on their way to participate in demonstrations in Selma, Ala., Miller participated in diner sit-ins with George Haley -- the former ambassador to Somalia under Bill Clinton and brother of Roots author Alex and one of the first black law students admitted into the University of Arkansas.

He knew Flannery O'Connor, C.D. Wright, Maya Angelou, Frank Stanford and Howard Nemerov. I remember him talking about the time he and Jordan spent the night dancing with Ciardi and his wife at Ralph Ellison's apartment in Harlem, and how Ellison insisted on walking the four of them to their car because he didn't want four white friends on the Harlem streets after midnight without a black presence to vouch for them.

He saw Eudora Welty at a reception in New York.

"Everyone else was dressed for Sunday morning church, and she was in a wash-dress and a shapeless cardigan sweater with what seemed to be kitchen slippers," Miller recalled. "And she was treated with such awesome respect by everyone that all of us felt terribly overdressed."

"I don't know of any poet who can express more clearly and beautifully the humorous and serious thoughts of this modern world," former President Jimmy Carter, who counted Miller as a mentor, told me in 2001.

"I have always had a kind of frustration about not having had an adequate liberal arts education," Carter said. "So I've tried to make up for it by studying and writing myself. Maybe 10 years ago I had written a few poems, not even good enough for me to want to show them to anybody in my family. And Miller Williams came down to Plains, I got to know him and I told him that I would really love to learn more about poetry. In effect he took me under his wing as a student and was a very tough taskmaster in assigning me the same kind of literary textbooks he used in college courses. I began to struggle with poetry then."

Carter spent thousands of hours over an eight-year period writing what became his first book of poems, Always a Reckoning.

"The wonderful thing that I had with Miller was that he could tell me that a line or a word was inferior, but I never let him give me a word instead," Carter said. "That was the deal we had and I stuck with it. So he would say, 'This line has an artificial rhyme and you're straining to say something.' He would recognize it, and so I would try to correct it."

The obituary would not note that I was also one of Miller's padawans. He taught me, as surely as he taught all those students that passed through the UA writing program. He used to tell me that Ciardi used to tell him that poetry was the art of lying one's way to the truth, which is a useful idea. But I prefer Miller's own working definition of poetry as the use of language to communicate more than the words seem to say in such a way that the reader cannot help but be pulled into the conspiracy of creation. Miller's poems give voice to our inchoate thoughts.

...

Miller once told me that, when he became (briefly unquestionably) famous after reading his poem at the Clinton inauguration, he was recognized in a drugstore by a 60-ish man. "Are you Miller Williams?" he asked.

"Yes, sir," he responded.

"Well, I just wanted you to know I didn't watch the inauguration -- I'm a Republican businessman -- but I read about you and your poem in The Wall Street Journal. I was skeptical, but the poem was there so I read it. Well, I want to tell you, I took it home with me at noon that day, and I said to my wife, 'Honey, I understood a poem.'"

"Sir," Miller said, "I'd rather hear that from you than from a hundred English professors."

Miller's poems are constructed of plain words; they aren't obscure or ambiguous. They mean what they say.

"It is almost inexpressibly important to me that my poetry be accessible to anyone who cares to read poetry, whatever their station in life, whatever their background," he said. "At the same time, I want to write poetry that acquits itself as serious poetry to those in an academic position to make that judgment."

A few years ago, for a program on Miller that ran on AETN, journalist Ernie Dumas asked Miller what he'd like his legacy to be.

"Professionally, apart from my children and their children, I would want to have my poetry read and appreciated -- on paper as long as there are words on paper," Miller said. "It would make me very happy on my deathbed to believe that in a thousand years someone would actually open a book and read one of my poems."

That would be monument enough.

The family of Miller Williams requests that memorials be sent to:

The Miller Williams Poetry Series, University of Arkansas Press, McIlroy House, 105 N. McIlroy Ave., Fayetteville, Ark. 72701 or The Harrison/Whitehead endowment, Fayetteville Community Foundation, P.O. Box 997, Fayetteville, Ark. 72702

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

Style on 01/11/2015