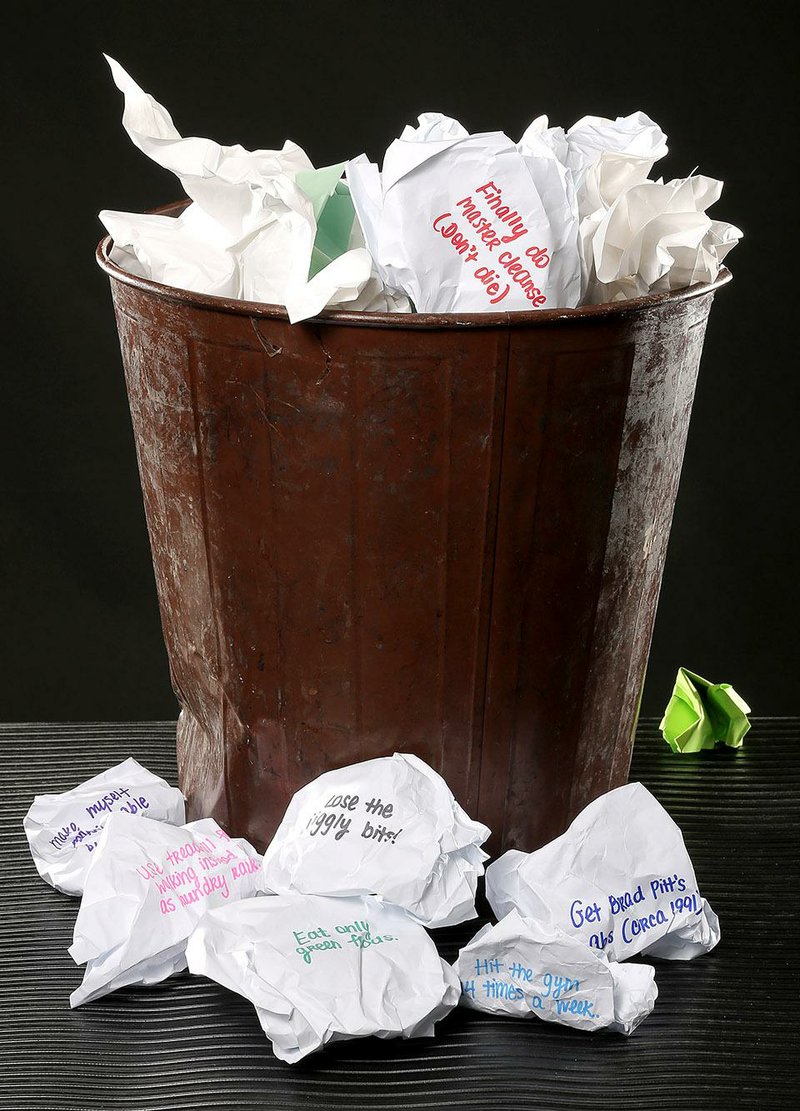

Resolution-makers like to imagine a new year can come with a "new you," but can old bad habits be forgot and never brought to mind?

Overhauling one's health and fitness is not as simple as leaving unhealthy habits behind when the clock strikes 12:01 Jan. 1, sports psychologists say. Bringing about a lifestyle overhaul that yields improvement in weight, wellness or fitness is difficult to begin and even harder to maintain.

About 45 percent of all Americans usually make New Year's resolutions -- with about 38 percent of those setting their sights on losing weight, the most popular goal -- but only 8 percent are successful, according to a 2014 University of Scranton study published in the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

While 75 percent work on their goals through the first week of January, the number drops to 64 percent once February hits, and it falls to 46 percent after six months, researchers found.

"People tend to make resolutions on an emotional basis, because they're feeling good will and optimism, which is not anchored in reality," says University of Arkansas at Little Rock psychology professor Elisabeth Sherwin. "We want to feel like we want to transform ourselves -- and we can -- but there's no fairy godmother. She doesn't show up; I hate to break it to you."

A lot of factors are working against us, including unrealistic goals and poor advance planning, says Amanda Visek, an assistant professor of sports psychology at George Washington University.

"Very often if people make one of those errors, they're often making the other concurrently," Visek adds.

Human resilience in the face of failure also works against us. With goals like quitting smoking or improving diet or increasing exercise, people will try time and again to achieve them -- and fail just as often.

"Almost every goal succeeds to some degree before it fails. So even if it's successful for a month, or for two weeks, that feeling of control and empowerment for those two weeks feels really good," Visek says. And the attention resolution-makers receive when they're making healthier choices or have lost a few pounds is "powerful because people want that back."

And so, when people try again, they blame their earlier failure on external attributes -- wrong diet or gym or ineffective personal trainer -- or an internal attribute, such as a lack of will power, to be corrected next time.

Even while struggling, people are bombarded by social cues via fitness magazines, TV, etc., that cleaning up a diet or trimming pounds in something like "three easy steps" is eminently doable. "Look at the magazine rack, at Self or Shape magazine," Visek says. "If you dissect the cover, they all are sending messages, both direct and subliminal, that these things are easy."

Instead of promoting realistic goals such as "lose 1 or 2 pounds a week," those magazine covers will say, "Burn 1,000 calories easy."

"But you can't do that. It's not easy for anybody to burn 1,000 calories," Visek says.

Those messages are repeated so often that people believe them, she says, which contributes to what psychologists call false hope syndrome, characterized by unrealistic expectations about the ease of self-change.

"A big part of the false hope syndrome is this false confidence in our ability, that things will be easier and take less effort than they actually are," Visek says.

And that's why people often will pledge to make the same health-related goals five or six times before they achieve six months' worth of success, she says.

Optimism and confidence are great, "as long as it's earned confidence," built upon a person's past behaviors and skills that point to success, Visek says.

GOALS AND PLANNING

To find a reasonable goal, a resolution-maker first has to assess how much he's doing now and set a small, very specific goal of improvement from there, psychologists advise.

Visek says that when she's counseling resolution-makers, she'll ask about this goal. "The first follow-up question that I ask is, 'How often are you doing that now?'" Visek says. "Their first answer is what they eventually want to achieve. But about 99 percent of the time it's not a realistic goal."

For example, someone may not be exercising but wants to start hitting the gym five or seven times a week, Visek says. It's important to see the discrepancy between the goal and reality, and scale the goal back so they're closer together at first, psychologists say.

"You should choose something very specific: 'I am going to exercise an hour a week,'" Sherwin says. "Get to where that fits in naturally for ... you." It usually takes at least six weeks to make a habit. "And only then do you say, 'I'm going to exercise twice a week.'"

Exercisers shouldn't start with a seven-days-a-week goal because, among other reasons, "a) the first day you oversleep, you have a problem, and b) it may not be healthy for you," Sherwin says.

Once the resolute person has a reasonable goal in hand, it's time to make a plan, psychologists say.

"When people say they'll make diet-related changes, they underestimate the effort that is needed to truly do that," Visek says. "You have to expend a lot of time and energy figuring out how grocery shopping, cooking, will be different: What kind of meals will you make? When I go out to dinner with friends, how are my choices going to be different? What social pressures might I feel to order or drink different things? There are so many decisions and choices that have to be made, and when people make resolutions, they decide they're going to do something, but they don't plan. Planning is huge."

Failure can also come from making "all-or-none, dichotomous goals" that put success in terms of black or white, instead of allowing for gray shades of improvement.

If the goal is not to eat sweets, but a friend's birthday cake beckons at dinner, the dieter will focus on that sweet slipup and not think about his successes. So he might think the whole week is blown and restart on Monday instead of Sunday, she says.

"People tend to frame their goals in a way in which they're inhibitory, like cutting out sweets," Visek says. "That's not helpful because the goal isn't telling you what to do -- it's telling you what to cut out -- and the inherent question is what to replace it with. ...

"We want to frame our goals so they're forward-thinking and instructional so they direct you toward what to do versus what not to do."

Similarly, exercisers who want to move to, say, a seven-day-a-week schedule, need to consider how to adjust their current routine, how all that exercise will alter other parts of their lives; and there are smaller, practical considerations such as increased laundry loads and whether they have enough clothes. "I always tell people: 'Proper planning prevents poor performance,'" Visek says.

GETTING PUMPED

Motivation can come from internal rewards, such as an inherent love of breaking a sweat, or external, such as monetary rewards for hitting the gym, psychologists say. Extrinsic motivation is good for initiating a new behavior, like prying fannies off the couch, but intrinsic motivation is more powerful because it means we love what we're doing, psychologists say.

"We have to draw upon the different types at different times to reach our goals," Visek says. Extrinsic motivators, such as new workout clothes, "are probably going to be most helpful in the beginning to help them get up and going because they probably don't think they inherently find exercise to be fun," Visek says.

But, Visek says, an exerciser can shift from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation.

She offered herself as an example. "When I first starting running, it was extrinsic -- I was running for mileage and health outcomes in feet," to ease arthritis, Visek says. "I thought it was hard. ... But over the course of doing that, there was this sort of paradigm shift, because instead of focusing on mileage and results, I started tuning into more of how I felt when I was running, how I felt after I was running, all of these things that over time, I started to enjoy running and looking forward to running.

"Since then, now I would say I was a runner, but a handful of years ago, I would've laughed."

REWARDS FOR WEIGHT LOSS

Haleigh Clark, 23, a University of Central Arkansas student who started a weight-loss journey Aug. 5, knows something about finding motivation, even midyear.

In August, she and her roommates decided to get fit. Clark wanted to lose 75 pounds by her May graduation, and now she's well on her way to her goal. She says she was tired of being the "fat friend" and constantly overlooked, and her major impetus for changing her habits came in August when she felt her health was declining. She knew she wasn't going to feel better if she continued "to eat large pizzas and drink soda like no one's business," she says.

"You're doing it for yourself," Clark says of her intrinsic drive. "At the end of the day, it's all you have."

She's got some extrinsic motivation giving her boosts, too.

Clark's grandmother, who's into health and supports her efforts, told her she'd buy Clark something nice for every 25 pounds lost. At her first 25 pounds, it was a new pair of shoes. She's closing in on a 50-pound prize.

She has found that signing up for 5Ks and buying new workout clothes create other incentives. She also looks to social media sites such as Pinterest, Instagram and blogs to get pumped up and keep motivated. And she takes pictures of herself frequently to mark her progress.

"I read that if you wear fitted clothes, you feel so much better, because you can see that you're transitioning and transforming," Clark says. "You will be so much surprised how much better you feel with fitted clothes. It's weird how something so small can help."

Sherwin says to keep goals "very small, very immediate," and even count little actions that buy time to achieve goals tomorrow, such as making preparations for a healthful breakfast.

"And then, when you've done that, put a check next to it and say, 'I did it,'" she says. "And enjoy it."

ActiveStyle on 01/19/2015