RAPHINE, Va. -- The sprawling truck stops just off Interstate 81 in Raphine, Va., offer diesel, hot coffee and "the best dang BBQ in Virginia." There's something else, too: a small-town doctor who performs medical exams and drug tests for long-haul drivers, an innovative effort to keep his beloved family practice afloat.

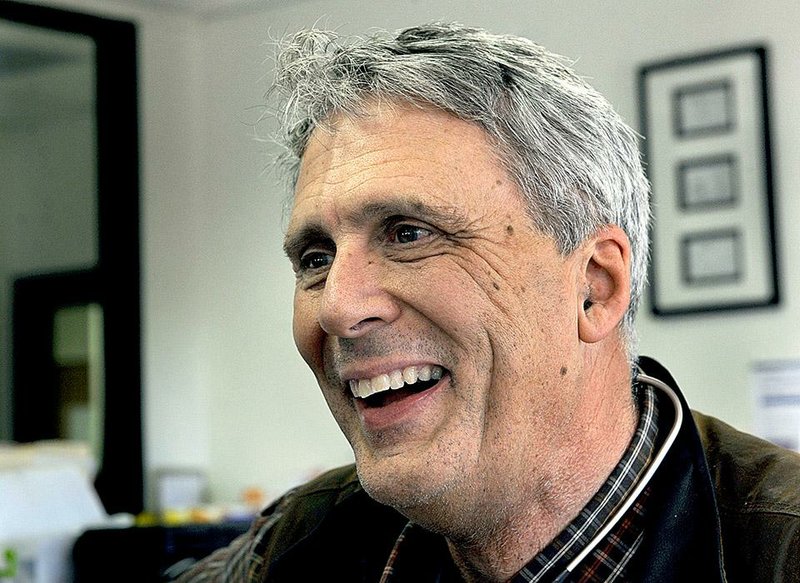

At a time when doctors are increasingly giving up private practice, Rob Marsh still operates his medical office in tiny Middlebrook, Va., about 15 miles from Raphine. He makes house calls and checks on his patients who are hospitalized -- sometimes late at night. He knows which tough, leathery farmers will blanch as soon as they spot a needle.

For the past 2 1/2 years, Marsh, 58, also has reached out to another medically neglected population: the truck drivers who spend their days on interstates, many never home long enough to find a primary-care physician.

About 20,000 trucks pass through Raphine each day. As many as 1,000 drivers a night sleep at the local truck stops, dwarfing the town's population.

At the TA Petro truck stop, where Marsh opened his clinic in July 2012, drivers wander in the stores killing time, looking at chrome for their trucks, hunting gear, fried strawberry-rhubarb pies in waxed-paper packets. They can get oil changes, work out, take showers. And now they can get U.S. Department of Transportation-mandated physicals, flu shots or treatments for sore backs.

Construction equipment grinds steadily. Robert Berkstresser, a self-made businessman who owns the truck stop, is intent on turning the truck stop into a destination. He is adding a laundromat that will page drivers when their clothes are clean, a movie theater, a barbershop and what he says will be the country's first truck-stop pharmacy.

Marsh plans to expand the clinic, too, adding workers and space so he can treat more patients. He sees locals at the clinic by appointment only but allows truck drivers to walk in and hopes to adjust his hours to serve them better.

It seems that drivers like to get on the road first thing in the morning, he said, and take care of medical needs at the end of the day. So Marsh, who already spends most nights making house calls and hospital rounds, often finds himself treating patients at the truck stop at 8 p.m., long after the clinic has technically closed. He is thinking about whether on some nights he can keep it open even later.

With electronic medical records, Marsh can forward information from his exams to other health-care providers so drivers can get medication or follow-up care farther along their routes.

One recent day, driver Terry Jenkins went to Marsh's office for one of his employer's mandatory random drug tests. In the past, he said, it wasn't so simple. One time, a dispatcher contacted him to order a test, and he had to park his truck in the lot of a big-box store, take a taxi to a hospital 20 miles away, wait a couple of hours there for test results, then take another taxi back to his truck.

"This is a whole lot easier," Jenkins said.

Marsh's warm, easygoing manner -- laughingly taking heat from a Cowboys fan for the Redskins' dismal season, kneeling to offer a sick toddler an orange lollipop -- belies his intensity.

A decorated U.S. Special Forces medic, Marsh survived, just barely, the disastrous firefight involving U.S. forces in Somalia made famous by the book and movie Black Hawk Down. He returned to Middlebrook, his hometown, for his next call to service: caring for his friends, the farmer down the road, the people sitting in the pews alongside his family. In December, an industry group named him the 2014 "Country Doctor of the Year."

"I don't make no decision unless I can discuss it with him," said Chester Perry, a retired truck driver who is recovering from a heart transplant and visited the clinic in Raphine recently.

He and Marsh sat knee to knee, so close their foreheads were almost touching, talking about how to manage Perry's dialysis while strengthening his heart.

Marsh made plans to visit that weekend at the nursing home where Perry lives.

"He's a fine old country boy," Perry said. "A good doctor. And a good friend."

And like most country doctors, he's finding it increasingly difficult to keep his practice afloat.

Less than a decade ago, more than 60 percent of physicians worked independently, said Walker Ray, vice president of the Physicians Foundation, which surveys doctors each year. Now only about a third do; the rest are employed by hospitals and large medical groups.

In 2014, the percentage of doctors who work alone, like Marsh, fell to 17 percent.

"People in solo practice just really can't make it," Ray said. "Always on call, rarely gets time off, the demands are always there. Most people can't do that."

So when Berkstresser asked Marsh to open a clinic at his truck stop, the country doctor saw an opportunity. In Raphine, many drivers pay Marsh in cash, providing a steady stream of income without the usual insurance reimbursement complications. Because the drivers come and go, there's little of the intimacy he has with his longtime patients. But the drivers get doses of Marsh's warm, personal approach. And he hopes long term that the clinic will provide enough of a financial cushion for him to keep treating patients the way he believes in.

"I'm a survivor. I'll make this work," Marsh said. "I'm willing to make those adaptations because I love what I do so much."

Glenn Maddox, who tows broken-down trucks, visited Marsh's office recently while waiting for his next call.

"My ear hurts, and I can't hear real good," he said. The doctor grabbed his light and took a look.

"Looks like it needs to be flushed out," he said.

Maddox started driving in 1974 and remembers a lot of times when he was sick on the road but had no doctor to go to and so just toughed it out.

"It's definitely a job that's very hard on your health," Maddox said. "Your lifestyle, your eating habits, the stress of delivery times and traffic -- it just goes on and on."

Sometimes, one of Marsh's nurses will set up in a room in the truck-stop restaurant, offering to check drivers' blood pressure while they wait for lunch. Other times, a nurse will go from cab to cab, dispensing flu shots.

As he was treating a fourth-generation farmer with bronchitis at the truck stop one recent day, Marsh told the man that when he started his practice, he had 30 dairy farmers as patients. Now he can count patients who are dairy farmers on one hand.

"It's not economically viable anymore," Marsh said as the farmer nodded.

Outside, trucks lumbered through the parking lot, which is scheduled for another expansion soon.

SundayMonday on 01/25/2015