ROCK HILL, S.C. -- For a moment, Clarence Graham's heart raced. Fifty-four years after he and eight fellow black men served a month of hard labor for sitting at a whites-only lunch counter, a judge declared that they had been wrongly convicted of trespassing and their records would be tossed.

"In my heart, I was leaping," Graham said.

Family, friends and supporters in the packed courtroom clapped and cheered Wednesday as Judge John Hayes vacated the sentences for the men known as the Friendship 9. Seven of them were in court. One had died, and another couldn't make the hearing. The men who were there -- some surrounded by their children -- smiled as they heard the ruling.

They had "never felt guilty of anything," Graham said.

Hayes said the men had been prosecuted "solely based on their race."

"We cannot rewrite history, but we can right history," he said.

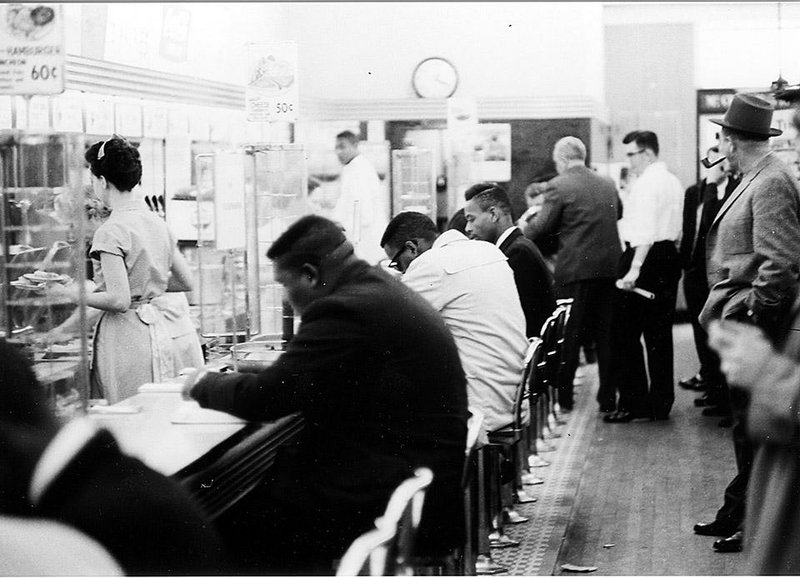

The eight college students and one civil-rights organizer were convicted in 1961 of trespassing and breach of peace for protesting at McCrory variety store in Rock Hill.

They had a choice of spending 30 days in jail or paying a $100 fine. All opted for jail.

The men's refusal to pay into the segregationist town's city coffers served as a catalyst for other civil disobedience. Demonstrators across the South adopted their "jail, not bail" tactic.

At the time of the Friendship 9's demonstration, in February 1961, about a year had passed since a sit-in at a segregated lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C., helped galvanize the nation's civil-rights movement. But change was slow to come to Rock Hill.

Thomas Gaither arrived in town as an activist with the Congress of Racial Equality. He encouraged Graham and seven other students at Rock Hill's Friendship Junior College -- W.T. "Dub" Massey, Willie McCleod, Robert McCullough, James Wells, David Williamson Jr., John Gaines and Mack Workman -- to violate the town's Jim Crow laws by ordering lunch at McCrory's.

Last year, author Kim Johnson published No Fear For Freedom: The Story of the Friendship 9. She is the one who went to Kevin Brackett, the prosecutor for York and Union counties, to see what could be done to clear their records.

Brackett agreed the men were wrongly convicted and pushed for the hearing.

"There was only one reason these men were arrested. There was only one reason that they were charged and convicted for trespassing, and that is because they were black," he said in court Wednesday.

Then he apologized to the men: "Sometimes you just have to say you're sorry," Brackett said.

South Carolina has a long history of revisiting and trying to right its past during the civil-rights movement. In recent years, both a Democrat and Republican governor apologized for state troopers opening fire on black protesters at South Carolina State University in 1968, killing three.

Last month, a judge threw out the conviction of a 14-year-old black boy who was executed after being convicted for killing two white girls. His trial lasted a day.

In the weeks leading to Wednesday's hearing, the Friendship 9 recalled how different Rock Hill was at the time of their arrests. Today it's a thriving exurb -- about 25 miles south of Charlotte, with blacks and whites living side by side in the city's neighborhoods.

But in 1961, it was a typical small town in the segregated South. Blacks weren't allowed to attend white schools. When the nine opted for jail instead of fines, they spent the month working on a chain gang. Even then, they said, they didn't let the arrests break their spirit. To pass the time while they were digging ditches and loading dirt onto trucks, they sang songs, most notably Sam Cooke's "Chain Gang."

For years, they didn't talk about the arrests because of the stigma of spending time in jail -- even for a month.

But now they want the younger generation to know about the struggle for civil rights and to believe that nonviolence -- as preached by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. -- can work.

Graham said he had a message for those in Ferguson, Mo., and other places protesting the white police shootings of black teenagers: "Protesting is fine ... but do it in a nonviolent way."

Information for this article was contributed by Meg Kinnard and Jeffrey Collins of The Associated Press.

A Section on 01/29/2015