FRANKFURT, Germany -- Greece will need more help from eurozone countries to manage its debt because the country's finances and economic performance have deteriorated since a new government took office, the International Monetary Fund reported Thursday.

The report, which assessed the prospects of Greece being able to repay its international creditors, was couched in technocratic language and did not mention any Greek leaders by name. But it amounted to harsh criticism by the IMF of the way Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras has managed the country since taking office in January.

Whether intended to, the report, released shortly before a national referendum Sunday in Greece over whether to accept a debt-relief package opposed by the Tsipras government, has potential geopolitical dimensions. The tone of the report could feed existing perceptions that the IMF and eurozone leaders are no longer willing to negotiate with Tsipras and are hoping a yes vote in the referendum will prompt his government to resign.

Tsipras and his leftist government have been campaigning for a no vote, telling voters that rejection will compel the lenders to back off from their insistence that Athens raise the money it needs to repay its staggering debt by making even deeper cuts to public spending as well as raising taxes on businesses.

The IMF denied Thursday that it was trying to influence Greek politics and said the timing of release of the report was not related to the referendum.

A senior IMF official said the organization released the report Thursday because elements of it were leaking out.

"I don't see how we can be seen as interfering with anything," the official said. He spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to the media publicly.

Greece's eurozone colleagues have been urging voters to accept the creditors' offer, even though it technically expired with Tuesday's default, saying only a yes vote will open the way for renewed negotiations on a third bailout.

"The Greek government is rejecting everything with the suggestion that if you vote 'no' you will get a better or less tough, or more friendly, package," the head of the eurozone's group of finance ministers, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, said. "That suggestion is simply wrong."

The Greek finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, said Thursday that he would step down immediately if Greeks voted yes. Varoufakis, who even before the leftist government was elected had argued that much of Greece's mountain of debt needed to be forgiven, has been a key player in the months of talks that have led to the current impasse.

Meanwhile, a spokesman for the Greek government said the report confirmed its position that Greece needs a break on its debt.

Before the new government was elected in January, the IMF said, Greece's economy had reached a point where Athens would have been able to make debt payments in years to come. But in recent months, the government has weakened efforts to improve the economy and has slowed the sell-off of government assets that would have raised cash, the IMF said. And that has created a new financing gap, the fund's report said.

"Coming on top of the very high existing debt, these new financing needs render the debt dynamics unsustainable," the IMF said in the report. "If the program had been implemented as assumed, no further debt relief would have been needed."

The program refers to the international bailout package that a previous Greek government agreed to in 2012, which called for strict economic measures that the Tsipras administration rose to power opposing.

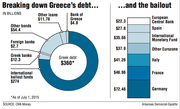

Greece needs an additional $56 billion in debt relief, the IMF calculated, of which about $40 billion would come from other eurozone countries.

But even those sums are probably understated because the report was prepared before the situation in Greece deteriorated even more this week.

The government closed Greek banks Monday to stanch an outflow of deposits, and on Tuesday, it missed a loan payment of about $1.7 billion that was due to the IMF. Analysts said the country is effectively bankrupt.

At the very least, the IMF said, Greece will need to delay repayment of much of its debt. More likely, its creditors will need to write off some of the debt and absorb losses.

That word is likely to be received very poorly in the other eurozone countries that hold most of Greece's debt. The cost of further debt relief will be borne mostly by taxpayers in countries like Germany, where resentment of Greek behavior is already high.

"Creditors want a change in government in Athens," analysts at Eurasia Group, a consultancy, said in a note to clients Thursday. "And they see this Sunday's referendum as their first possibility to achieve it."

Many economists regarded Greece's debt as having been unsustainable even before Tsipras and his Syriza party took office.

The IMF itself had previously urged European governments to write down some of Greece's debt.

And in 2012, when Greece was still in the throes of a recession, the European Union promised to provide further debt relief to Greece so long as it met budgetary targets and kept pledges to make changes in the economy under its bailout program. But last year, after Greece appeared to be getting back on its feet, the leaders said they were no longer certain that Greece needed that relief.

On Thursday, the IMF report also said the country's debt load had been on its way to becoming manageable because of low interest rates and an improving economy.

The progress was squandered by government policies in recent months, the IMF report implied, because the government has failed to implement a program intended to improve the functioning of the economy. Among other things, the program requires Greece to abolish rules that limit competition among professions such as accountancy and law and lead to higher fees for businesses and individuals.

Plans to sell government assets, already behind schedule when Syriza took office, are even more in jeopardy, the IMF said. Revenue from sales of state assets amounted to about $3.5 billion as of the end of March, the IMF said, far short of a target of about $55 billion by the end of the year.

The new government has placed further conditions on privatizations that will make it even more difficult to sell assets such as airports or real estate. And one of the main categories of assets -- stakes in the country's largest banks -- has become nearly worthless because of questions about whether the banks can survive.

"Under these circumstances," the IMF said, "it is not reasonable to assume revenue from bank sales."

On Thursday, elderly Greeks, some struggling with walking sticks or being held up by others, formed large crowds outside the few banks opened to help pensioners without ATM cards get access to money.

Elsewhere in Athens, campaigners battled for visibility as time to reach voters was running out before Sunday's referendum. "Yes" posters appeared for the first time around the city, and rival campaign rallies were scheduled for the same time tonight, 800 yards apart, in the heart of the city.

About 6,000 supporters of the Greek Communist Party attended a rally outside parliament Thursday, urging voters to cast invalid ballots in protest of Greece's continued membership in the European Union.

Some Greeks said Thursday that they were unsure how to vote, because they were unsure what Sunday's vote was for.

"If it's saying 'no' to austerity, then it's a 'no' from me," said Costas Christoforidis, a 37-year-old farmer. "But if we are rejecting Europe, I disagree with that."

Information for this article was contributed by Jack Ewing, Liz Alderman, James Kanter and Niki Kitsantonis of The New York Times; by Carol J. Williams of the Los Angeles Times; and by Derek Gatopoulos and Costas Kantouris of The Associated Press.

A Section on 07/03/2015