The Spirit of '76 stirred and divided Americans--for all of us were not Patriots, and some of us remained true to the English parliament and crown. Public opinion was divided in the mother country as well. Consider the views of one Englishman who rose to speak in the midst of a colonial war that would prove more than a colonial war but a whole Novus Ordo Seclorum, as it still says on the dollar bill, or A New Order for the Ages.

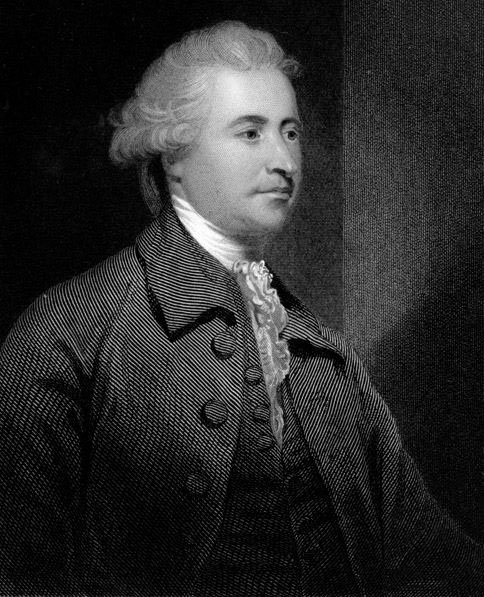

Eloquent rhetorician, thoughtful student of history, insightful analyst of events in his own time and prophet of things to come, Edmund Burke had decided ideas on any number of subjects, including what makes nations great and what undermines them. The member of parliament for Bristol understood very well what was at stake in the coming conflict over the nature of the British empire: the empire itself.

Author, orator, thinker, and loyal but not blind servant of the crown, he would not, could not, keep silent. Any more than a faithful sentry would fall asleep at his post and fail to sound the alarm at approaching catastrophe. His every thought and impulse, fortified by his experience as a statesman and its hard-won lessons, told him that His Majesty's ministers were embarked on a disastrous course. Their colonial policy was not only wrong in principle but, perhaps worse in the eyes of a statesman, sure to fail in practice.

A great statesman has qualities beyond calculation. He has vision, and the will to see it through to fruition. Edmund Burke fully envisioned the ruin his colleagues were inviting by their persistence in adopting punitive rather than conciliatory policies toward British America, which might yet be saved for his Sovereign. So it was only to be expected that he would speak out, however futile the effort would prove, in favor of "Conciliation With America" on the 22nd of March, 1775.

It would not be the last time Edmund Burke's counsel and foresight would be ignored--and vindicated by sad events. For in the years ahead he would prove as incisive a critic of the French Revolution as he would a defender of the American one.

IF AN EDITOR had to choose a single phrase to sum up Burke's extensive oration on the wisdom of conciliating America, an oration that used to be studied in courses on rhetoric--back when rhetoric was still widely studied--it would be Burke's pointed warning that "a great empire and little minds go ill together.'' Even by his time, the American character had already been formed. And he knew it was not one that could be bullied by an imperial establishment far removed from these shores and, as it turned out, from reality. Anybody who thought Americans were likely to yield to superior force, even the force of the mightiest empire in the world in its day, didn't know Americans. Or the beliefs that had shaped us. And that we would hold fast to. Come what may.

And came it did: one defeat and retreat after another, out of which would somehow emerge victory, independence, and a new order for the ages. By some mysterious process--Providence?--these royal colonies would emerge from that trial by fire free and independent states. We had won our independence, and Great Britain had lost the most promising part of a vast empire.

Our revolution would be more than a colonial rebellion. It would be a test of our beliefs. Those beliefs would be given their most concise and enduring expression in the Declaration of Independence of July the 4th, 1776:

We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.

Those words would have to be redeemed in blood before they would become among the best known and most influential in the course of human events. They would become the creed of a revolution that goes on across the world even today. That revolution would prove successful not only because of the vision and courage of America's founding generation, but because of the blind willfulness of those who thought they could bully us into obedience. They didn't know us. Edmund Burke did. His assessment of the American character proved remarkably accurate, and may it ever remain so:

"In this character of the Americans, a love of freedom is the predominating feature which marks and distinguishes the whole . . . . Sir, from these six capital sources--of descent, of form of government, of religion in the Northern Provinces, of manners in the Southern, of education, of the remoteness of situation from the first mover of government--from all these causes a fierce spirit of liberty has grown up. It has grown with the growth of the people in your Colonies, and increased with the increase of their wealth; a spirit that unhappily meeting with an exercise of power in England which, however lawful, is not reconcilable to any ideas of liberty, much less with theirs, has kindled this flame that is ready to consume us."

The British couldn't say they hadn't been warned, and by their leading statesman at that, one for the ages, however little they appreciated his foresight at the time.

To those of his colleagues who believed their Force Acts would render us pliant subjects, Edmund Burke responded: "The temper and character which prevail in our Colonies are, I am afraid, unalterable by any human art. We cannot, I fear, falsify the pedigree of this fierce people, and persuade them that they are not sprung from a nation in whose veins the blood of freedom circulates. The language in which they would hear you tell them this tale would detect the imposition; your speech would betray you. An Englishman is the unfittest person on earth to argue another Englishman into slavery."

It was not only the American spirit that the rulers of that great empire failed to apprehend when they adopted a tyrannical course in these colonies, but their own. They could not see that what they might have preserved through vision, they would lose by folly. Or as Edmund Burke warned his colleagues, "a great empire and little minds go ill together."

NOW IT is we who find ourselves with a great empire, or at least with all the responsibilities of one, however loath we are to acknowledge it. For we never sought an American empire. With all our being, we reject any such idea, respecting others' freedom as we love our own. But over the many hard years, as one threat after another materialized, we've been obliged to accept imperial responsibilities from time to unhappy time. Not out of imperious ambition but in self-defense. Despite the happy myth of an America isolated from all the world's troubles and intrigues, it was never so. We tend to forget that even our Revolution was part of a world war, fought with the critical aid of an international alliance with a still royal France.

The more supercilious commentators of our day have an annoying--and ignorant--habit of explaining that the ways and wisdom of the past are outmoded in these very modern, even post-modern days because, after all, our times are so much more complicated than those of our forefathers. They have no idea of the sophistication the generation of '76 showed in managing the most complex of challenges. For first they used British power and resources to dislodge the French from the North American continent, and then used the French to win our freedom from the British. Not exactly amateurs at statecraft, these founding fathers of ours.

Whether through the long twilight struggle called the Cold War or now, deep in a war on terror that indecisive leaders refuse even to call by that name, the burden of empire has been thrust upon us. Shall we be up to bearing it? Or will we again see that a great empire and little minds go ill together? This much is clear: Nothing so girds the spirit and informs the mind like memory. Which is why, on sunny days like this July the Fourth, we recall all the dark days we have overcome, and are renewed.

Editorial on 07/04/2015