The social worker's bills were as suspicious as they were numerous.

Counseling sessions for dead patients. Sixty-two hours of one-on-one counseling in one day. Weeks of 12-hour-plus days. And the kicker: 99.99 percent of the time, the invoices claimed the most costly service he could provide.

Those bills and thousands of others went into the vast federal Medicare system, and out came taxpayer dollars. A lot of them. And they all ended up with Thomas Craig Burns and his Mountain Home business, Road Less Traveled Counseling.

To report Medicare fraud or suspicious billing activity in Arkansas, call:

1-800-HHS-TIPS (447-8477) or 501-217-9561

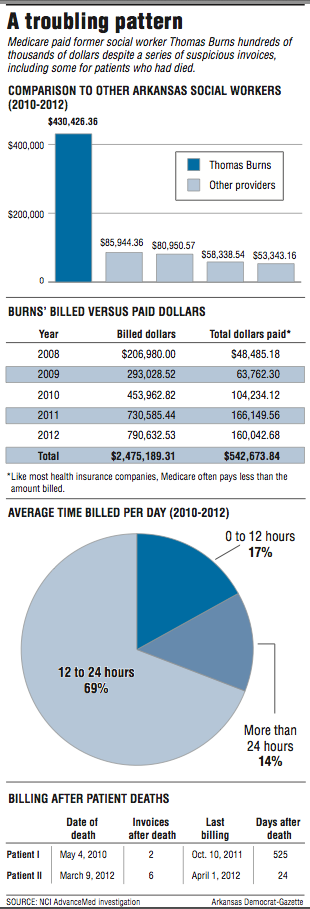

Over five years, documents show that Burns, 59, billed Medicare for $2.5 million and that the federal program paid him more than $500,000, all while he continued to submit bills that stretched the bounds of plausibility.

In 2012, Burns received the most Medicare payments of any similarly qualified social worker in Arkansas. He also ranked 10th in Medicare payments among more than 13,000 social workers nationwide, according to federal data published by The Wall Street Journal.

That year, federal investigators finally caught on. But documents obtained by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette show that, by then, Medicare had missed a series of opportunities to stop Burns from collecting more money.

Those missed opportunities raise further questions about the ability of Medicare and its contractors to spot fraud before paying out large sums of money, a problem highlighted over the past year by The Wall Street Journal, the U.S. Government Accountability Office and other government watchdog groups.

The fraud Burns committed was pretty straightforward. He sent in bills and was paid for services that he never provided. And he appears to have had little concern that Medicare would scrutinize even the most unusual invoices, documents show.

Medicare officials say they have put in place new safeguards over the past few years that are aimed at preventing "phantom billing" fraud, the kind Burns committed.

Federal fraud investigators and insurance industry monitors say Medicare is still years away from effectively catching fraud cases like Burns' on the front-end.

Lou Saccoccio, CEO of the National Health Care Anti-Fraud Association, estimates that each year the $600 billion Medicare program still pays out "tens of billions of dollars" in fraudulent billings.

That doesn't include estimates of wasteful spending in the program, which provides health insurance for people ages 65 and older and those under 65 who have certain disabilities or renal disease.

The problem, Saccoccio said, is that it's still too easy for fraudulent bills to blend in with legitimate invoices in the Medicare program, which covers 54 million people and pays more than 1.2 million providers and suppliers.

Provisions in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act aimed at fighting fraud by using data analysis have helped, but many of the changes haven't been fully implemented into the Medicare program, Saccoccio noted.

"It will take some time for [the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services] to get better at ferreting out these outliers, the anomalies where you have one person in a certain geographic area where you go, 'Whoa, what's going on here?' I know they want to do a better job. I think they're slowly getting there," he said.

Mike Fields, special agent in charge of the Dallas regional office of the inspector general of the Health and Human Services Department, was more critical.

"Nobody's trying to discern if there's a pattern. They're too busy. They're paying claims -- $4.4 million worth a day -- they're just processing claims. Nobody's really looking into it," he said.

"All that stuff comes after the fact. Even Medicare and Medicaid, most of the time, the two systems don't talk. It's an uphill climb," Fields said. "I think that technology could take away a lot of this stuff, but it's just not at that point where it's been implemented yet."

Drugs, second chances

Burns practiced for about 10 years in Mountain Home, a town of 12,000-plus people nestled in the Ozarks and known for its retirement appeal, pristine waterways and hiking.

He provided counseling services mostly for people suffering from alcohol or drug addiction.

In the 1990s, Burns practiced as a private social worker in Texas, but in 1993, documents show, a client reported to the Texas State Board of Social Worker Examiners that Burns was abusing a client's prescription medication. Two years later, the board received another report that Burns appeared incoherent during a visit from a board supervisor.

Then in 1997, Burns was convicted of fraud involving a controlled substance after he admitted forging a prescription for Vicodin, court documents from Harris County, Texas, show. He served about eight months of a two-year prison sentence.

The Texas board revoked Burns' license, but after prison, he applied for a social worker license in Arkansas. In 2001, along with his application, Burns submitted a letter disclosing his drug addiction and troubled past in Texas.

The Arkansas Social Work Licensing Board, which is empowered to grant certain exceptions for felons, approved Burns for a probationary license and required that he participate in random drug testing.

Even though he had committed a felony that normally would have excluded him from receiving Medicare dollars, Burns benefited from fortunate timing.

According to court records, Burns' offense occurred July 28, 1996 -- a mere three weeks before a federal law took effect that excludes felons from billing Medicare if they were convicted of certain controlled substances crimes, particularly relating to "unlawful ... prescription, or dispensing of a controlled substance."

So, after receiving his social work license, Burns obtained a Medicare provider number that he used in his Mountain Home practice, and he began billing.

An unknown outlier

In the winter of 2013, Andrea Lee, an investigator with Medicare contractor NCI AdvanceMed, had to use six separate charts and tables to show the extent of Burns' conspicuous billings in a five-page letter to the Arkansas Social Work Licensing Board.

Lee's letter was attached to a formal complaint against Burns seeking disciplinary action or revocation of his social work license.

Between Jan. 1, 2008, and Dec. 31, 2012, Burns was the only licensed clinical social worker in Arkansas to bill for one-on-one counseling sessions of 75-80 minutes in length, the most costly procedure for which he could bill.

In fact, of all Medicare providers in the state, only two others had billed for the type of counseling Burns said he was providing. Both of the other providers billed for one counseling session each, but Medicare did not pay either one, Lee wrote.

But Burns was rarely denied payment. During those four years, Burns billed Medicare nearly $2.5 million for 5,737 face-to-face counseling sessions of 75-80 minutes apiece. Medicare paid him $542,660.94 for the sessions. (It also paid him $12.90 for the only other services he said he provided -- seven group psychotherapy sessions.)

The majority of the payments came between 2010 and 2012. During that time, Medicare paid Burns $430,426.36 -- more than five times the amount paid to the next-highest-paid social worker in Arkansas, who received $85,944.36 over that time, according to Lee's investigation.

Many of the payments to Burns covered bills that appeared to be unbelievable. Burns billed daily for 12-24 hours of one-on-one counseling 69 percent of the time, and another 14 percent of his billings were for 24-plus-hour days, Lee found.

In 2012 alone, Burns billed so much that he would have had to work straight through 14 weekends. He billed for 14.5 hours on Thanksgiving, 22 hours on Memorial Day, 23.75 hours on the Fourth of July, and 24.5 hours on Labor Day.

Lee also found billings for face-to-face counseling sessions with two patients after they had died.

In 2010, Medicare paid Burns for a counseling session a day after a patient died, and then five months later, he was paid for another session for the same patient. In 2012, Burns billed six separate times for sessions with another patient after the patient had died.

Medicare didn't notice any of this while it happened. Burns' billings drew scrutiny only because a sharp-eyed patient complained, documents show.

Not adding up

In July 2012, the patient complained to AdvanceMed that Burns had billed Medicare for services she didn't receive.

The patient told investigators that she was agoraphobic: afraid of places or situations, usually public, that might cause her to panic or feel embarrassed. The patient said she had been treated by Burns a "long time ago" and began seeing him again in April 2012 after her regular therapist had to stop practicing because of medical problems.

She met with Burns twice in April, and he scheduled future sessions to occur in her home. But Burns never visited her, despite billing her for 16 "unique dates of service," according to the AdvanceMed investigation.

Over the next few months of 2012, investigators received two more complaints from patients.

One patient reported not seeing Burns since 2011. Yet, he had submitted bills under the patient's name for 51 days in 2012.

Another woman reported seeing Burns three times, but her bill showed that he'd charged for 49 days of visits. The patient noted that Burns charged Medicare for 75-minute to 80-minute sessions, but that he visited with her for only 45 minutes or less on the three occasions he saw her.

The patient noted that on her last session, "Mr. Burns was preparing for a yard sale, spending most of the session asking her to advise him on how to price items."

AdvanceMed requested the patients' records from Burns, but he never produced them. On Nov. 28, 2012, he responded by email, saying he was too overwhelmed with work to gather the records.

"It doesn't appear I will meet your deadline. Submit your overpayment if you have to," he wrote.

Three months later, AdvanceMed summarized the patient complaints and Lee's analysis and sent them to the Arkansas Social Work Licensing Board.

In response, Burns wrote the board a letter, detailing his "personal pain and turmoil" related to the dissolution of his marriage, his wife's struggle with methamphetamine addiction and his own struggle with depression.

He wrote that he had lost his office manager two years before. He said he then put his wife in charge of billing, which he said he "knew little to nothing about." That was a mistake, he wrote, as well as giving her access to his bank account.

"I realize I stuck my head in the sand because I wanted to avoid conflict," he wrote in the March 18, 2013, letter.

Burns told the board that he was willing to pay Medicare back "anything that was improperly billed" and turn his billing over to an outside person or agency.

"I am willing to do anything the board instructs to keep my license," he wrote. "If the board looks through my file, it will see I am a good therapist who can be of service to my community if I can stay on this present course of recovery."

A day after his letter, the board received a second complaint, accusing Burns of obtaining prescription Klonopin from one of his patients. Burns didn't respond to the allegations.

In August 2013, the board held a hearing on the complaints against Burns and voted to revoke his license. Burns did not attend.

Dollars and cents

Reached early last week, Burns said he didn't have time to talk with a reporter and said he would call back. He didn't return the call by the close of business Friday and didn't respond to other voice-mail messages. The phone discussion came after a reporter had left several messages on Burns' cellphone over three weeks' time requesting comment for this story.

The newspaper pieced together a picture of Burns' past using public records in Arkansas and Texas, most of which were obtained under state open-records laws.

When asked about Burns' case and whether that type of fraud could still slip through Medicare's safeguards, a spokesman for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services declined to comment, saying the program doesn't discuss specific cases.

Spokesman Tony Salters wrote in an email that Medicare has implemented a fraud-prevention system that can automatically detect and stop payment on "certain improper claims." Medicare also has started pilot programs that feed "waste, fraud and abuse leads" to Medicare anti-fraud contractors for "early intervention," he wrote.

Salters also cited the success of a group of law enforcement agencies in detecting and prosecuting fraud over the past several years.

In June, the U.S. Department of Justice announced the arrest of 243 people who were accused of defrauding Medicare of about $712 million in false billings.

The arrests, made in 17 cities over a three-day period, were part of an operation by Medicare Fraud Strike Force teams -- specially trained groups of agents from the FBI, the Department of Health and Human Services, the Justice Department, and local law enforcement.

Since 2009, the Justice Department touts that it has recovered more than $15 billion in health fraud cases, about $3.3 billion in fiscal 2014 alone.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Alex Morgan, the health care fraud criminal coordinator for the Eastern District of Arkansas, said he couldn't comment on Burns' case or provide specific numbers on how much money has been recovered by his office in health care cases.

But Morgan stressed that beneficiary complaints -- which led to Burns -- are one of the most critical tools federal investigators rely on to detect and stop fraud.

"The point is that if people scrutinize their bills, they're doing a great service," he said. "It's all dollars and cents. It's important that we get it back."

Fields, who supervises 60 agents that investigate fraud in Arkansas and four other states, said his agents and federal prosecutors are always looking to recoup improper or fraudulent payments. But many times, the money is already gone.

"You try to get as much as you can, but sometimes it's just gone. A lot of them are like these regular street-level criminals, the minute it's in their pocket, it's out," Fields said.

Saccoccio said that recovery can only go so far.

"The key to all of this is going to be prevention and data analytics, and trying to get out ahead of these guys," he said.

At a court hearing in Little Rock last month, Burns entered into a plea deal with federal prosecutors and admitted that he "sometimes billed for services that were not rendered," during a time in which "he was overwhelmed with marital problems, episodic drug use and depression."

Specifically, he pleaded guilty to one count of health care fraud and agreed to pay $71,305.15 in restitution to Medicare, an amount that included at least 190 therapy sessions for one client -- valued at $10,664.94 -- that he never provided.

Standing before U.S. District Judge D. Price Marshall Jr., Burns said he regretted defrauding Medicare.

"I did what I did, and I'd like to be accountable for it," Burns told the judge. He is scheduled to be sentenced in September. He faces up to 10 years in prison.

SundayMonday on 07/05/2015