Andy Warhol and nature.

Seems incongruous, doesn't it, that the wan-looking pop art pioneer in the white fright wig and sunglasses -- known for large works inspired by advertising (such as Campbell's Soup cans), modern urban life and popular culture celebrities such as Jackie Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe -- would be in any way associated with the great outdoors. Who knew he even went outside, except at night?

Exhibit

‘Warhol’s Nature’

Through Oct. 5, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, 600 Museum Way, Bentonville

Hours: 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Monday and Thursday, 10 a.m.-9 p.m. Wednesday and Friday, 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Saturday-Sunday. Closed Tuesday. Note: 10 a.m. openings continue through Labor Day (Sept. 7).

Admission: for “Warhol’s Nature,” $4, free for age 18 and under. Museum admission is free.

Info: crystalbridges.org, (479) 418-5700

But this artist was no stranger to Mother Nature.

And the proof is in "Warhol's Nature" at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, a new exhibition that opened Saturday. It was created by curator Chad Alligood, who was co-curator of the museum's "State of the Art" exhibition, which closed Jan. 19.

"Warhol's Nature" is the first exhibit to explore this topic, he says. Most of the works are from the collection of The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, which co-organized the exhibition with Crystal Bridges.

"This is a side of Andy Warhol you don't know about," Alligood says. "From his earliest images in New York City, he was drawing landscapes, animals, flowers ... all were important to him."

A year and a half in the making, "Warhol's Nature" also reflects Alligood's belief that the influential Warhol is "a great gateway for those who are new to art."

It was for him.

"I grew up in the rural south, raised in the tiny town of Perry, Ga. I didn't go to museums."

The first Warhol art Alligood saw was in the first museum he entered, at Harvard University in 2002. That museum's collection included several Warhol screen prints and paintings.

"That was my introduction to Warhol and to art," he says. "I came late to art."

He may have arrived late, but Alligood made up for lost time. He earned a bachelor's degree in the history of art and architecture from Harvard, completed his master's in art history at the University of Georgia and has finished his doctorate coursework at the City University of New York. He also has taught art at Brooklyn College and was a collections fellow at Cranbrook Art Museum in Bloomfield Hills, Mich., before coming to Arkansas.

Warhol's accessibility and the nature theme, he says, make this exhibition a "great fit" for Crystal Bridges.

"This is an expansive view of Warhol's approach to nature," Alligood says. "This exhibit fits our mission at Crystal Bridges -- to celebrate the American spirit in a setting that unites the power of art with the beauty of nature. This exhibition explores that.

"There is much beauty here," he says. "[Warhol] was inspired by advertising; he came out of commercial art in the 1950s and was attuned to making beauty ... he was drawing for greeting cards, advertisements, album covers. His images connect immediately; they are vibrant with saturated colors. Because of that, people today already know how to look at it."

Warhol's genius, Alligood says, was his ability to generate images in a way that popular culture already does.

"He used screen printing for repetition, something advertising does again and again, hoping you will buy something. He lifted directly from that logic and made it part of his creative process." Warhol repeated images many times, shifting colors and size.

The artist, Alligood says, "was a sponge and a mirror. He absorbed all kinds of stuff from the outside world; he was an avid reader and looker, a voyeur. On his first trip to Los Angeles, he was enamored [of] how shiny everything was and all the advertising, everywhere. His influences were vast and varied and had everything to do with the world around him."

In the art world Warhol was "a way forward after abstract expressionism. He used representative images; you're looking at people in paintings again."

So, Alligood says, there is a feeling of familiarity with Warhol even if one is not familiar with the specifics of his art.

"Warhol's transformation of pop culture and nature is very accessible -- that's what sets him apart," he says. "Anyone can have an experience in nature without prior knowledge of nature. This exhibition offers that. I hope people see a Warhol they never knew and that they will look at their world and nature with a new perspective."

...

The word ''nature'' in the exhibition's title has a double meaning: Mother Nature and Warhol's own nature and how they intersect and interact.

"He was both attracted to and repelled by the natural world," Alligood says. "I think he was constantly looking for a way to control it."

That love/hate relationship created a tension that seems to reveal itself in two photographs in the exhibition: in Untitled (Warhol Flowers V) by William John Kennedy, he appears wary and detached as he stands amid sunflowers and in front of one of his huge Flowers pieces. In the compelling Andy Warhol standing in the woods at Philip Johnson's Glass House in New Canaan, CT by David McCabe, the trees could be seen as embracing or devouring the artist.

Some of Warhol's difficulty with nature stemmed from his extreme sensitivity to the sun.

"He couldn't be outside without being covered up by clothing, a hat and sunscreen," Alligood says. "He loved being outside, but couldn't do it a lot."

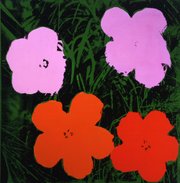

Despite that, Warhol clearly felt a connection to the natural world. He created more than 10,000 images of flowers alone, according to the essay Andy Warhol Museum chief archivist Matt Wrbican wrote for the exhibition catalog. Warhol made donations to conservation groups and parks; he also owned land on the beach in Long Island, N.Y., and more than 40 acres of wild land near Aspen, Colo., on which he pledged not to build.

"I think having land and not ruining it is the most beautiful art that anybody could ever want," Warhol says in the catalog, a quote from The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again).

He also had a fondness for animals, especially dogs and cats.

"Warhol lived with his mother at one time in New York City with 25 cats," Alligood says.

What surprised Alligood was the reverence Warhol showed for animals in his art.

"He approaches these creatures in his art as portraits and elevates them; there is a lightness, a beauty, an integrity ... a reverence. I wasn't expecting that."

Warhol also was very interested in taxidermy. He bought a stuffed Great Dane dog from an antiques dealer.

"It was rumored to have belonged to [film director] Cecil B. DeMille. He named it Cecil and it stood guard in his studio during most of the 1970s."

And yes, Cecil will be displayed at Crystal Bridges, he says.

...

For Alligood, "Warhol's Nature" was a "unique experience to take a dive into one artist's work."

"Most of my work has been multiple voices, such as 'State of the Art,'" he says. "'Warhol's Nature' was a single focus on a historically important artist, diving into his psyche. I came away understanding anew how he managed his own identity. It made me look at how I present myself and how I interact with others."

Part of what drove Warhol through his life and career was a desire for control, Alligood says.

"He was trying to understand the world, I think. He was very invested in routine and repetition; he had the same lunch every day. Routine and repetition made his world make sense."

In nature, Warhol found something he could not control as he did his own image, Alligood says.

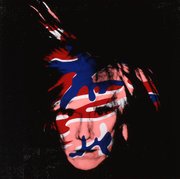

That reality surfaces in Alligood's favorite works by Warhol -- the self-portraits.

"We have one in this show, a 1986 camouflage overlay. It intersects with this image of himself. In this self-portrait, he's working in the same vein as when he was painting Jackie Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe, elevating himself to celebrity.

"With the camouflage, he's addressing the complexity of identity," Alligood says. "Camouflage is designed to recede into nature; it addresses the natural world and its intersection with his own nature within.

"We all present ourselves in a certain way; we perform our identity, especially in today's digital age with online avatars. It's so funny; even in this moment, we're just starting to understand the complexity of that ... [Warhol] looked at it 30 years ago."

Style on 07/05/2015