Politics often seems the enemy of art, for politics forbids the admission against self-interest or the equivocal gesture, the acknowledgment of any of the gray territories in which art dwells. Politics requires staying on message, toeing the line and keeping discipline. If politics is about doing what is possible, if it's about taming dreams into substance, then art is about exploring the ineffable reaches of the invisible realm.

Neil Young has earned the right to do what he wants and for the past 49 years that's exactly what he has done. At times this has yielded strange and wondrous revelation; at other times it has betrayed a certain restlessness of heart. He was too intelligent to accept the rock star veneration forced on him in the 1970s, and so he spent a lot of the '80s experimenting with styles and spiting his record company. By the '90s he was seen as one of the elders, a godfather to both punk and grunge, while he continued to make loud and ferocious new music. In recent years, his output has gotten more spotty. He has become kind of a rock 'n' roll Woody Allen -- enabled by past success and reasonable expectations to make any sort of record he pleases.

His best work, from 1968's "Sugar Mountain" to 2012's "Walk Like a Giant," has mostly presented the singer-guitarist in a faux naif mode, as a child wising (or wised) up in a world not of his making. Good Neil is evocative with his guitar and clumsy with his words, in part by design. He says more with his one-note eight-bar solo on "Down By the River" than in any of his lyrics, which range from occasionally pretty brilliant ("Powderfinger," "After the Gold Rush," that part in "I Am a Child" where he asks "What is the color, when black is burned?") to serviceable and insipid ("Welfare mothers make better lovers").

Although he has never given up his Canadian citizenship, he has lived in Northern California since the '70s and has never been shy about expressing his political opinions. While those opinions might generally seem to mark him as the hippie Antonin Scalia wants you to seek out, he's not entirely reliable. He endorsed Ronald Reagan for president and wrote "Let's Roll," a song inspired by the final words of Todd Beamer, one of the passengers on Flight 93 who tried to take control of the plane from terrorists planning to fly it into Washington on Sept. 11, 2001, resulting in its crash into a Pennsylvania field far short of its target.

Less than five years later, Young had soured on George W. Bush and was singing "Let's Impeach the President." Just recently he objected to Donald Trump's co-option of his song "Rockin' in the Free World" (an indictment of George H.W. Bush's "compassionate conservatism" which is as often misread as a jingoistic anthem as Bruce Springsteen's similarly badly used "Born in the U.S.A.")

While Young is admirably engaged with the wider world, it seems unlikely that anyone looks to him for his philosophical or political insights despite his folk singer affectations, aside from "Ohio," about the May 4, 1970, shooting of four students at Kent State. It's a song Young would later write about with some ambivalence, saying in the liner notes to his 1977 compilation Decade that it was "ironic" he "capitalized on the death of these American students."

"Southern Man" and "Alabama," the unsubtle South-baiting anti-slavery songs from Young's 1970 album Harvest that inspired Ronnie Van Zant of Lynyrd Skynyrd to write "Sweet Home Alabama" and later for Patterson Hood of Drive-by Truckers to write "Ronnie and Neil," probably deserve to be addressed as well. But to do so here and now would take us down one of those rabbit holes better explored with a free afternoon and a Web browser. Suffice it to say that while Young's mansion has many rooms, in the '60s and '70s he was not a particularly political songwriter.

...

These days, however, 69-year-old Young seems to have taken on the persona of an Internet scold, one of those social media animals with a hot take ready on everything from the sterility of digital music and government surveillance of its citizens to tabloid journalism. And he has the means to indulge his muse, whipping out notional three-chord songs about anything that streaks across his interior skies and putting out almost instant albums.

To his credit, for the most part he has managed to continue to make interesting, if not essential, guitar-based rock 'n' roll. His 2010 collaboration with Daniel Lanois, Le Noise, was perhaps overambitious, but there was something genuinely thrilling about the woolly mammoth that was 2012's Psychedelic Pill, a double-CD set that reunited him with the surviving members of Crazy Horse. While the Instagram filter gimmickry of 2014's A Letter Home (Young recorded his voice and acoustic guitar directly onto producer Jack White's lo-fi Voice-O-Graph recording booth, resulting in an instant vinyl record) is distracting, a couple of the resulting tracks are charming.

But then there are disasters, like 2009's concept album about his electric car Fork in the Road ("The awesome power of electricity/stored for you in a giant battery") and 2003's puzzling and dour Greendale, a musically thin and lyrically incoherent concept album about a dysfunctional family. There are times when Young would have been well served by a record company A&R man with the power to lock up his masters.

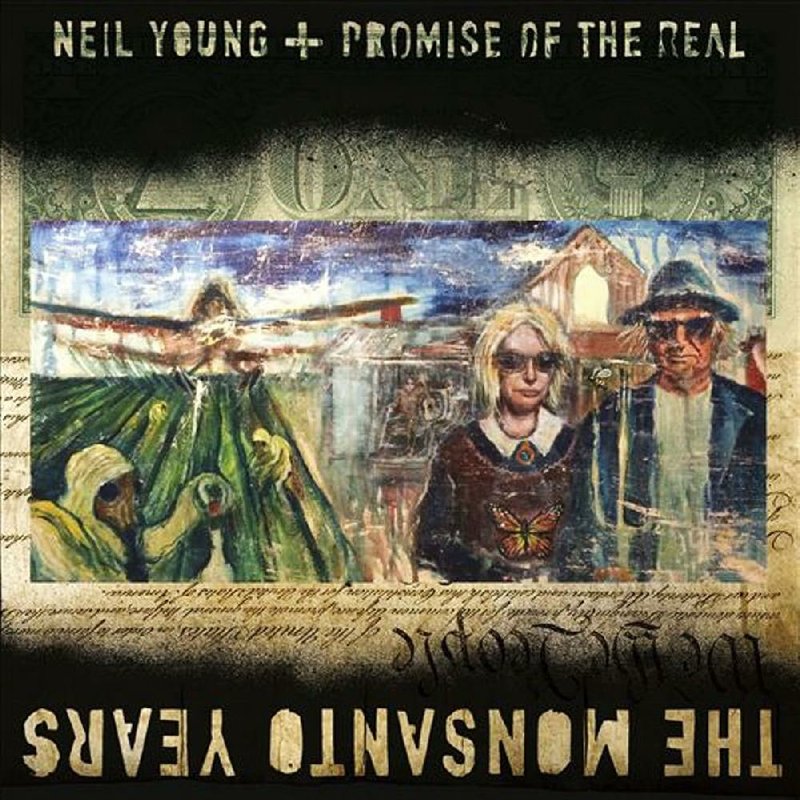

The Monsanto Years, released last week, is his 36th studio album and quite possibly his worst record yet. And not just because of its at times risible lyrics railing against corporate farming, GMOs (genetically modified organisms) and "bankers too rich for jail." Musically it's a mess, an underwritten quasi-punk buzz that feels improvised ... and not in a good way. It might be encouraging to note that Young's fully plugged in again, after the relative quietness of November's Storytone (a record that still feels so new to me that I don't really have a cogent opinion of it -- I guess it's about Neil's breakup with Pegi, his wife of 36 years, and his new romance with Daryl Hannah).

That's not to say Young isn't sincere in his concern for American farmers -- after all, he was one of the organizers of the original Farm Aid concert in 1985 -- or talking about important issues; it's just that this is a concept album criticizing an agribusiness conglomerate, an ungainly and terribly specific white whale. It sounds like the premise of a Saturday Night Live skit that never made it to air. It's literal-minded, shrill and thuddingly overt: The cover painting features a punkish parody of Young and Hannah as the farmer and his wife in Grant Wood's American Gothic.

Young recorded the album with the help of Willie Nelson's sons Micah and Lukas, along with Lukas' band Promise of the Real. Recorded in the Teatro movie theater in Oxnard, Calif. (the same theater where Willie Nelson recorded his Teatro album) in January, it feels unfinished and skeletal, a few easy chord progressions and clunky sing-along choruses that hammer at the corporate villains Young calls out -- Starbucks, Wal-Mart, Chevron and Monsanto. The title track is a particularly unartful screed:

When you shop for your daily bread and walk the aisles of Safeway

Find a package to catch your eye at Safeway

Choose the picture of an old red barn on a field of green

With the farmer and his children, to complete the scene at Safeway

The family seeds they used to save were gifts from God not Monsanto

Their own child grows ill near the poisoned crop

While they work on, they can't find an easy way to stop Monsanto ...

That's simply lazy writing -- it's not art. It's spew. It may be true, it may be morally justified, but it doesn't work in any context, even as a punkish shout-along. There's no rhythm, no meter, no sense of playfulness or joy. This is the sound of an old man's tantrum. It's not pretty.

Marginally better are the forgettable songs, like the album opener "A New Day for Love," a genial blandishment with some crunchy guitar. "Wolf Moon" is a pleasant acoustic number with a nice harmonica break that is jerked back in line with the album's theme in its final lines:

Seeds of life your glowing fields of wheat

Windy fields of barley at your feet

While you endure the thoughtless plundering ...

Oh dear. From there, it gets worse, with Young anticipating his critics with the chiding "People Want to Hear About Love" which has all the depth of a series of trolling tweets: "Don't talk about the beautiful fish in the deep blue seas dyin'/People want to hear about love." (And what's wrong with that? Paul McCartney and I would like to know.)

By the time you get to the fourth and fifth tracks, the anti-Wal-Mart "Big Box" and the excruciatingly bad single "A Rock Star Bucks a Coffee Shop" -- which manages to be self-aggrandizing and self-trivializing with lame couplets like "I want a cup of coffee but I don't want a GMO/I like to start my day off without helping Monsanto" and off-key whistling -- you're either laughing at Young or embarrassed for him. Probably both. Maybe the session was fun to play.

That's not to say there's no place for politics or protest in music. If you want to hear an effective anti-Wal-Mart song, listen to Steve Earle's remarkable "Burnin' It Down" off his 2013 album The Low Highway. Beth Ditto's "Standing in the Way of Control" is a great example of danceable politics. It's just that what Young and company have recorded here are more like the spontaneous chants of random Occupy members than the work of professional musicians invested in their craft. It's not that the sentiment is so wrong -- although Young's lyrical approach is broad and scattershot -- it's just that the execution is shoddy. We expect better from Neil Young.

Fortunately, we'll probably get it -- in a matter of months, if not weeks. Young has become the rock-star equivalent of a cable shout-show host -- there's always something new to be enraged about: Old man, stay off my lawn, I'm a lot like you were.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

Style on 07/05/2015