COLUMBIA, S.C. -- South Carolina, the first state to secede from the union, dispatched with a lasting symbol of the Civil War on Thursday as Gov. Nikki Haley signed a law removing the Confederate battle flag from the grounds of the Statehouse.

The flag, which flies in front of the 19th-century Capitol building, is set to come down at 9 a.m. CDT today.

Haley, a Republican, signed the bill in the Capitol surrounded by cheering lawmakers. She used nine pens, which will be given to the families of the nine victims of a June 17 church shooting in Charleston, which police said was racially motivated and which led to calls to remove the flag.

Haley described the shooting victims, including state Sen. Clementa Pinckney, as "nine amazing people that forever changed South Carolina's history."

She also praised lawmakers, including members of the House of Representatives, who engaged in a 13-hour legislative argument over the flag before voting at 1 a.m. Thursday to remove it.

"The Confederate flag is coming off the grounds of the South Carolina Statehouse," Haley declared.

She added that it would be lowered with "dignity" while noting that the decision was the product of shared pain over the Charleston shooting, and admiration for the acts of those in the historic black church who welcomed a white man into their midst, only to see him shoot and kill.

"The actions that took place are what will go down in the history books," Haley said. "Nine people took in someone that did not look like them or act like them, and with true love and true faith and true acceptance, they sat and prayed with him for an hour."

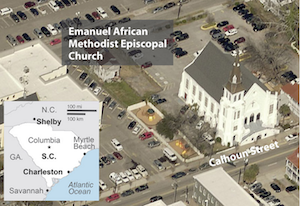

The massacre of Pinckney and eight others inside Charleston's Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church led to calls to remove the Confederate flag, not only in South Carolina but around the nation.

South Carolina's leaders first flew the battle flag over the Statehouse dome in 1961 to mark the 100th anniversary of the Civil War. It remained there to represent official opposition to the civil-rights movement.

Mass protests against the flag decades later led to a compromise in 2000 with lawmakers who insisted that it symbolized Southern heritage and states' rights. They agreed then to move it to a 30-foot pole next to a Confederate monument out front.

But even from that lower perch, the flag was clearly visible in the center of town, and flag supporters remained a powerful bloc in the state.

For Haley, the removal of the flag represents a reversal from her long-standing views. The governor, who was re-elected last year, had long supported the compromise that allowed the flag to fly at the Statehouse.

But on June 22, less than a week after the massacre in Charleston, she demanded that it come down. Lawmakers in the Republican-controlled Legislature quickly obliged.

A bill to take down the flag passed the South Carolina Senate on Tuesday. On Wednesday, the House spent hours discussing the flag.

The final vote in the House, 94-20, was well above the two-thirds' majority required to move the bill to the governor, but approval arrived after midnight, after a debate that stretched on for more than 13 hours.

Representatives shared anger, tears and memories of their ancestors. Flag supporters talked about grandparents passing down family treasures. Some lamented that the flag had been "hijacked" or "abducted" by the racially intolerant.

Republican state Rep. Mike Pitts recalled playing with a Confederate ancestor's cavalry sword while growing up, and said the flag reminds him of dirt-poor Southern farmers who fought Yankees, not because they hated blacks, but because their land was being invaded.

Black Democrats, frustrated at being asked to honor those who fought for slavery, offered their own family histories.

Rep. Joe Neal traces his ancestry to four brothers, brought to America in chains and bought by a slave owner named Neal who pulled them apart from their families.

"The whole world is asking, is South Carolina really going to change, or will it hold to an ugly tradition of prejudice and discrimination and hide behind heritage as an excuse for it?" Neal said.

State Rep. Christopher Corley, a Republican, called the debate over removing the flag "the most emotional issue our state will ever deal with."

Differing opinions over the flag continued Thursday. White House spokesman Josh Earnest praised the decision to remove the flag as "progress," while the Sons of Confederate Veterans sharply criticized the plan.

"The Sons of Confederate Veterans is dismayed that the politicians of the great state of South Carolina have traded their integrity for the fleeting benefit of appeasing those individuals and groups who do not let facts stand in the way of their objectives," Charles Kelly Barrow, the group's commander in chief, said in a statement.

The decision to remove the flag, Barrow said, "evidences a capitulation to the malicious campaign that has fanned the flames of divisiveness for the sole purpose of political gain. It is a politically convenient insult to the legacy of millions of South Carolinians."

Barrow also said that his members would continue to resist "the wave of cultural cleansing and political correctness that sullies" the names of their Confederate ancestors.

"No political act can erase the memory of these brave and good men," he said. "And as this particular flag comes down, thousands more are being lifted, for the St. Andrew's Cross stands not for hate, but for love."

Around the flag on the Statehouse grounds Thursday, there was a buzz of conflicting emotions. Anti-flag protesters were there, as they had been in recent days, but their signs, instead of calling for removal, held messages of relief.

Not everyone was happy, though. Michael French, 43, a contractor who lives outside Columbia, went with his son Chandler, 17, to take a picture of the flag before it was pulled down.

"Biblically speaking, any time there's something that causes division among men, it should be done away with," said French, who is white. "But I don't think that applies here, because there will always be something else" for protesters to protest about.

"They're going to want to take down the Confederate monument," his son predicted. "Everybody wants to be a victim."

Indeed, calls for the flag's removal in other states have been followed by attempts to remove other Civil War-era symbols. In New Orleans on Thursday, Mayor Mitch Landrieu asked the City Council to move three prominent statues of Confederate figures. He also suggested renaming Jefferson Davis Parkway, named for the Confederate president, who was a slave owner.

As drivers in South Carolina passing by the Statehouse honked in support or shouted obscenities, some people waved small American flags. Many took photographs near the Confederate flag.

An older white man with a cane posed by the flagpole, solemnly, as another man took his photo. Both declined to comment.

Tamela Stevenson, 49, who is black, posed with her children, too, wearing a big smile. She said her grandmother Annie Mae Robinson had always told her that the flag would never come down in Robinson's lifetime. She was right: She died 23 years ago.

"This just marks the beginning of South Carolina going forward and being with the rest of the world," Stevenson said. "I know it won't change everything, like the way people feel. But going forward, in the future, I think it will help."

Information for this article was contributed by Richard Fausset and Alan Blinder of The New York Times and by Jeffrey Collins, Meg Kinnard and Janet McConnaughey of The Associated Press.

A Section on 07/10/2015