Ever asked the Internet what your symptoms mean and gotten a response that seemed wacky or totally off base?

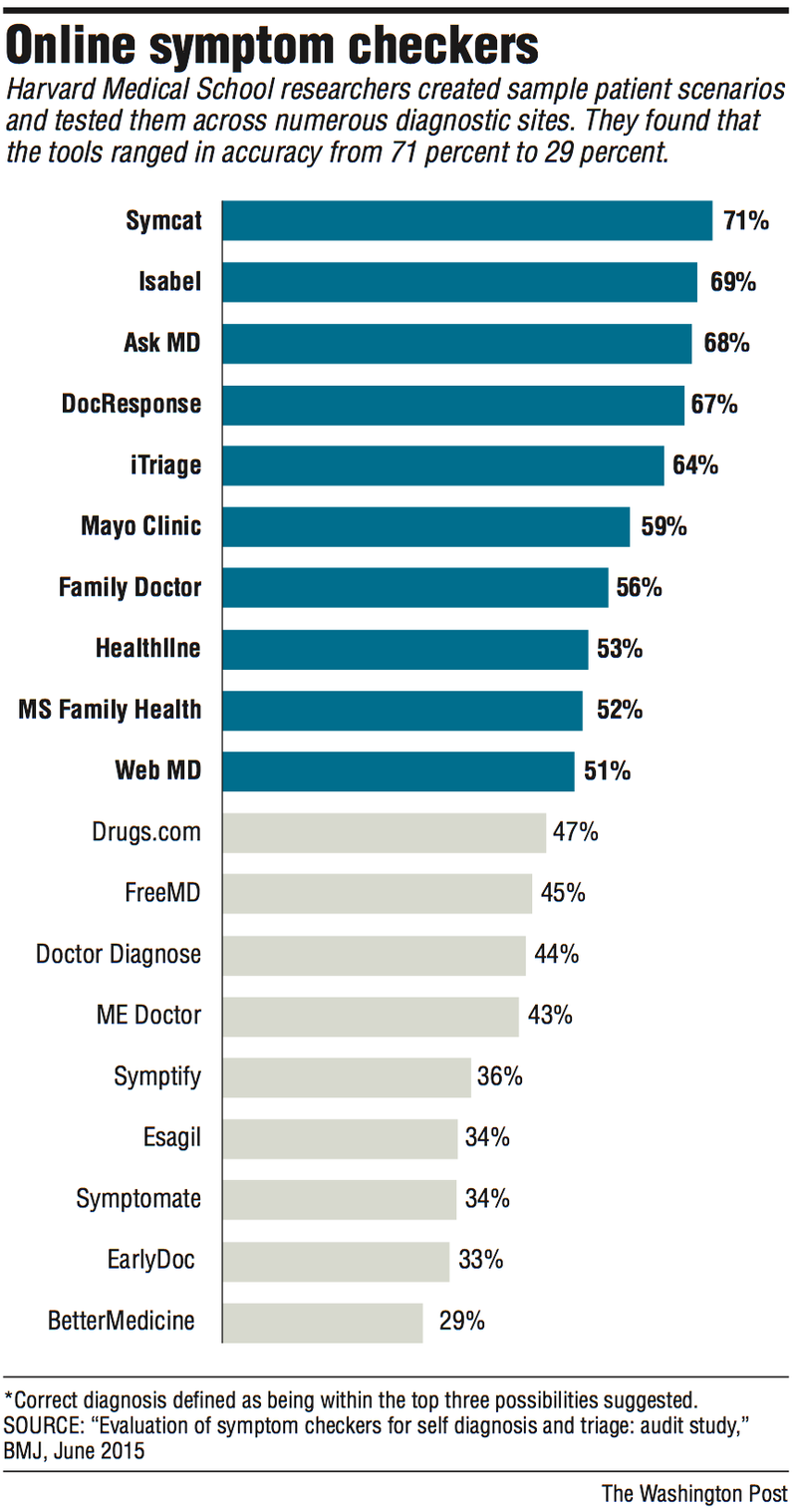

In an audit that is believed to be the first of its kind, Harvard Medical School researchers have tested 23 online "symptom checkers" -- run by brand names such as the Mayo Clinic, the American Academy of Pediatrics and WebMD, as well as lesser-knowns such as Symptomate -- and found that, though the programs varied widely in accuracy of diagnoses and triage advice, as a whole they were astonishingly inaccurate.

Symptom checkers provided the correct diagnosis first in only 34 percent of cases, and within the first three diagnoses 51 percent of the time.

"Our results imply that in many cases symptom checkers can give the user a sense of possible diagnoses but also provide a note of caution, as the tools are frequently wrong and the triage advice overly cautious," Hannah Semigran and Ateev Mehrota, researchers in health care policy and medicine at Harvard Medical School, and their co-authors wrote in the study.

Symptom checkers are interactive programs that allow users to type in the aches, pains and irritations they are experiencing. The sites may follow up with a series of questions designed to home in on a disease or condition. Most provide lists of possible diagnoses, usually ranked in order of how likely their algorithm suggests they match up to the information provided, rather than a single answer.

Early versions of programs that came out a few years ago did little more than search for key words, but many of today's symptom checkers are based on sophisticated algorithms that use branching or Bayesian inference -- a way of assigning probabilities to hypotheses -- that are theoretically supposed to do a better job.

GRAB-BAG ACCURACY

The researchers' evaluation, which was published in June in BMJ, the former British Medical Journal, consisted of running 45

patient scenarios (or as many as made sense on specialty sites

focused on certain types of conditions or demographics) on each of the symptom checkers.

Fifteen of the cases required emergency care; 15 required nonemergency care; and 15 may have required self care but did not necessarily require a medical visit. Of the 45 cases, 26 described common diagnoses while 19 described uncommon diagnoses.

The top scores were awarded when a site listed the correct diagnosis first. This rarely occurred.

Less desirable but still potentially useful for patients was when a site listed the correct diagnosis within the first three possibilities. Two sites returned a large number of diagnoses -- as many as 99 -- when particular symptoms were entered, a response that the researchers said was "unlikely to be useful for patients."

The researchers also looked at the accuracy of triage advice -- whether patients should seek care from a professional or should be able to treat themselves at home. They found that appropriate advice was given 57 percent of the time and that sites were better at sounding the alarm when patients were experiencing an emergency than when they weren't.

Four sites -- iTriage, Symcat, Symptomate and Isabel -- always suggested that users seek care.

BEATS DO IT YOURSELF

The researchers noted that the accuracy of the sites is roughly equivalent to telephone triage lines and better than using search engines to try to guess the diagnosis yourself.

But would an actual human being with medical training have done any better? The researchers said that it's hard to tell, since the same cases were not presented to medical professionals, making direct comparisons impossible.

With nearly two-thirds of U.S. adults using the Internet for health information, according to a recent Pew Internet Project survey, the accuracy of such services is becoming increasingly important.

In 2014, the Food and Drug Administration said that it would exercise "enforcement discretion" for mobile apps "that use a checklist of common signs and symptoms to provide a list of possible medical conditions and advice on when to consult a health care provider." That means that while creators of such technology don't need to apply to the agency for approval before commercialization, the FDA retains the option to take enforcement action if there are safety concerns.

ActiveStyle on 07/20/2015