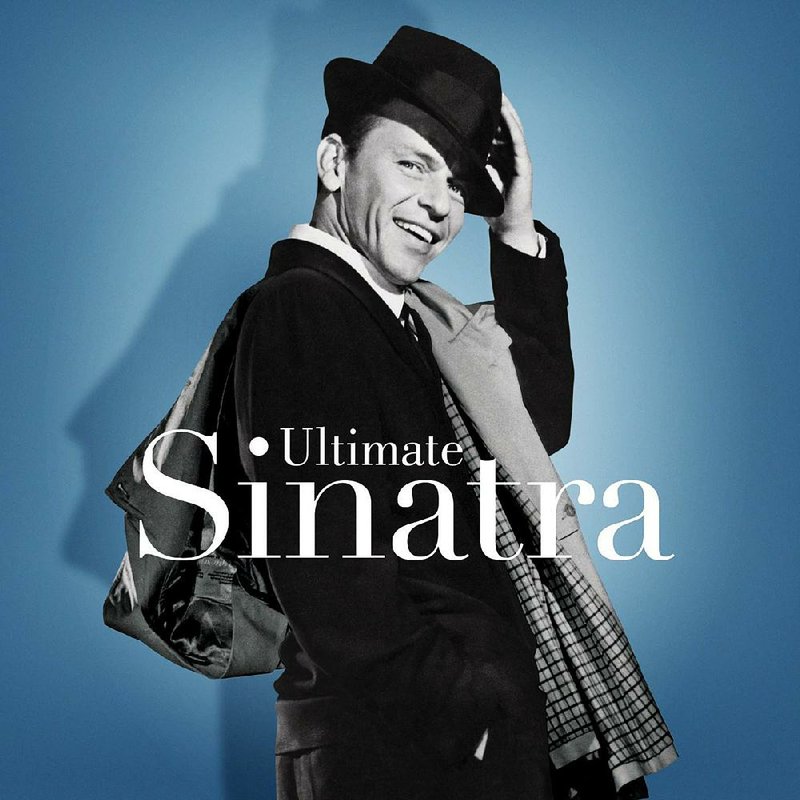

This has been a very good year for Frank Sinatra, who would be 100 years old on Dec. 12 had he not died in 1998. There was a pretty good two-part HBO special, Sinatra: All or Nothing at All, earlier this year, and we've just seen the release of Ultimate Sinatra (Capitol), the inevitable greatest hits package available in several iterations: A 25-track CD; 26-track digital download; a 24-track 180-gram two-LP package; and the deluxe 101-track four-CD and digital editions, which, for the first time, draw from the archives of all the labels for which Sinatra recorded -- Columbia, Capitol and Reprise.

In October, we'll get a coffee table book from Thames & Hudson with more than 400 photographs, about half of which have not been seen previously, forewords by Steve Wynn and Tony Bennett and afterwords by Nancy Sinatra, Frank Sinatra Jr. and Tina Sinatra.

In other words, we'll have the usual attempt to capitalize on an arbitrary number.

In one sense, Sinatra is gone and we will never see his like again. In another, he is always with us, like Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe, one of those pneumatic American icons floating over the cultural landscape like a cloud. We can see what we want to in them; if we stare long and hard enough, they seem to disappear.

In a real and enduring way, Sinatra belongs to all of us. He cuts across tastes, he is pop and art, and death and time have muted the darker aspects of his character. If we want to we can inspect his humanity -- we read all about his frailties and insecurities -- but all that happened so long ago, in a time before Twitter, when boorishness was a star's prerogative. We feel nostalgic for those Rat Pack days, even if they were over before we were born, when boys could swing and fornicate and drink and smoke and wear snappy clothes.

Sinatra was born the same year as Billie Holiday. He outlived her by almost 40 years, but in a way, I think of them as a kind of couple, twinned engines scrawling contrails across the 20th century -- the very first century when someone could become a recording artist. (And maybe the last century where records could matter as much as any other unit of cultural currency.)

Sinatra was more than a singer, he was a recording artist. What he did best and loved most was making records. Records are simulated performances assembled from discrete tracks recorded over hours, days, weeks, months or years. In the real world a week may pass between syllables. The artist layers and manipulates time, producing an artificial, durable and completely inauthentic illusion. Records are timeless because they are divorced from any particular moment. Sinatra has been dead for 17 years, yet we still hear his voice.

Whatever you think of Sinatra -- a lizardy voice poking through a scrim of blue cigarette smoke, some old would-have-been mobster with a microphone and a cocktail, the model for the crooner Johnny Fontaine in The Godfather -- attention must be paid. He practically invented pop singing as we know it. Unlike Bing Crosby or Louis Armstrong before him (or Elvis Presley after), he didn't just take a song at face value, as an entertainment. He pioneered the concept album -- it could be argued that Sinatra's 1955 collaboration with Nelson Riddle, Songs for Young Lovers, was the very first album that collected songs around a particular theme.

Sinatra understood that a pop song could aspire to high art, and that the right kind of singer could take it there. Sure, it took a special kind of singer, one who combined technical precision and sheer power with an unwillingness to compromise on musical quality and preternatural awareness of the communicative possibilities of the lyric.

He didn't just hit the notes, he made an emotional connection among the words, the music, the tempo and his personality. He redefined singing; he collapsed one set of expectations and erected another. Sinatra was a genius of style who risked much to do things his way. While he was a major star at Columbia Records in the 1940s, the novelty song craze of the early 1950s -- "How Much Is That Doggie in the Window" and "Abba Dabba Honeymoon" were typical hits -- nearly ended his career. Columbia urged him to go along with the fad and, when he resisted, dropped him.

At 38, Sinatra's career seemed over. But then Capitol Records, the only label to make him an offer, signed him for a small advance in 1953. Over the next nine years, he would make some of the most profound music in American musical history, working with conductor-arrangers Nelson Riddle, Billy May, Gordon Jenkins and Axel Stordahl.

Without Sinatra, there would have been no Bob Dylan to put out a surprisingly earnest collection of covers associated with him. Believe it, that's the way it is, that's how much he means, how much he matters. That he may have been a lout, a brute, a punk who threatened suicide to try to manipulate Ava Gardner, that he may have been the man who persuaded Sam Giancana to deliver Illinois and West Virginia to Jack Kennedy -- all that is incidental gossip.

A CREATIVE INTELLIGENCE

What's important about Sinatra is he changed the way we listen to pop music. He really was more than a voice. He was a creative intelligence, and while there were times when he flirted with becoming ridiculous -- his kooky version of "Mrs. Robinson," for example -- there's a genuine heroism in some of his work.

Some of the most interesting music he made was recorded well after his prime, after he'd become a legend and retired a couple of times. In his last years he lost some of his ability to trim back on his attack; he became a belter who, in concert, to preserve the ever-important phrasing of the lyrics, became a talker.

In retrospect, you can understand why he insisted that his recording partners on the technology-soaked Duets (1993) and Duets II (1994) -- an A-list that included Aretha Franklin, Liza Minnelli, Stevie Wonder, Tony Bennett, Carly Simon, Linda Ronstadt and Bono -- not be anywhere near the studio when he was recording his parts. For the most part, Sinatra is reduced to barking out those quarter notes.

It's more than competent, but he'd lost his legato -- the long-lined loosey-goosey phrasing, the death-defying, beat-lagging, once around the park, hurry now, here-comes-the-cavalry vocal charge he used to have. In his last years, Sinatra was always right on top of the rhythm, pinned down, swinging sure, but with less arc, less abandon. On those last records you can hear him popping everything, punching hard and furious as though he's not sure what he's got left and he wants to work it all out, to pump it dry. Rage, rage -- against the dying of the light.

It sounds as though Sinatra was angry with The Voice, like he wants to punish it for finally running out on him after all these decades, to slam it against the wall, to dash it to the stage and stand over it huffing and perspiring like a passion-killer while it bleeds into oblivion, into some kind of Samuel Beckett nothingness.

It's not close to his best work, but against all odds Sinatra acquires a certain intimacy with his recording partners, though they sang in separate studios weeks apart. These relatively sterile Duets albums (which both sold well; the first installment is still his best-selling title ever) are among his most interesting in that they allow us a glimpse of a dying lion, broken-roared but still defiant.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

Style on 06/07/2015