WASHINGTON -- An examination of the cellphone used by the engineer on the Amtrak train that derailed in Philadelphia last month, killing eight people, turned up no evidence that he was on the phone at the time of the accident, federal investigators said Wednesday.

"Analysis of the phone records does not indicate that any calls, texts, or data usage occurred during the time the engineer was operating the train," the National Transportation Safety Board said in an update of its investigation into the accident.

Investigators said an examination of Amtrak's records also confirmed that the engineer had not used the train's Wi-Fi system while he was operating the locomotive.

Still, at a Senate hearing on the derailment Wednesday, T. Bella Dinh-Zarr, vice chairman of the safety board, said the agency was continuing to examine more than 400,000 files of metadata on the phone.

"Things like the use of an app or other use of the phone has not been determined," she told members of the Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation.

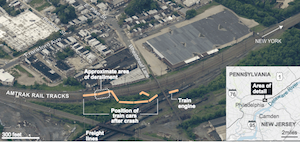

The question of whether the engineer driving the train, Brandon Bostian, might have been using a cellphone has been a critical part of the safety board's investigation into the crash, with investigators trying to determine whether he had been distracted by a call or text message. The train, en route from Washington to New York on May 12, was traveling at 106 mph as it entered a curve where the speed limit was 50 mph.

Bostian's lawyer, Robert Goggin, has said in interviews that his client suffered a concussion in the derailment and "has absolutely no recollection whatsoever of the events."

He also said Bostian had not been under the influence of drugs or alcohol and that his cellphone had been turned off and was in a bag. Goggin said his client remembered only "coming to, finding his bag, getting his cellphone and dialing 911."

Federal investigators said Bostian had been helpful in the accident inquiry, providing the pass code to his cellphone, which allowed investigators to gain access to the data without having to go through the phone manufacturer.

Investigators with the safety board had worked for weeks to match Bostian's cellphone records with other data -- including the locomotive event recorder, video taken from the train, recorded radio communications and surveillance video -- to provide clues about the cause of the accident, which also injured more than 200. But the investigation was slowed because of the way cellphone data and calls are routed across a carrier's network.

For example, investigators said, the voice calls on Bostian's phone were in one time zone, while the texts were in another. Investigators said they have worked with the phone carrier to validate the time stamps in several sets of records to correlate them all to the Eastern time zone, where the accident occurred.

Investigators are still trying to determine exactly what caused the Northeast Regional Train 188 derailment, though regulators told Congress that human error remains a likely cause.

During the Senate hearing Wednesday, officials reiterated the safety board's position that the accident could have been prevented if "positive train control" technology had been installed.

Amtrak has installed the technology in parts of the Northeast Corridor, which stretches from Washington to Boston. But the system, which can automatically slow or stop a train to prevent accidents, was not in operation on the stretch of track where the crash occurred.

After a deadly commuter train accident in California in 2008, Congress mandated that the technology be installed throughout the nation's railroad system by the end of this year. But that has proved to be a challenge both for railroads and regulators, in part because of costs of the system and because of the complexity of the technology, which provides real-time information to locomotives, engineers and train dispatchers about train speed and location. That allows trains to automatically respond to sensors placed along the tracks.

At the hearing, federal regulators said 71 percent of commuter railroads would not have the system in place by the deadline. The total cost to commuter railroads of installing the system will be $3.5 billion. To date, the commuter railroads have spent about $950 million, said Robert Lauby, an associate administrator at the Federal Railroad Administrator.

None of the large freight-train companies will have the system installed by the December deadline. Outside of the Northeast, Amtrak uses freight rail lines to operate. So far, freight rail companies have spent about $5.7 billion to install the system, according to the Association of American Railroads. The total cost is likely to be $9 billion.

Congress is considering extending the deadline to 2020 at the urging of some freight and passenger rail systems. But some lawmakers are opposed to an extension.

"We're a nation that put a man on the moon," said Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn. "We are operating a vehicle remotely on Mars. But our railroads have not yet implemented a technology that is existing, it's feasible and affordable."

A Section on 06/11/2015