Mysterious insects are on the move, munching about, creating concern and confusion.

What are they? What do they want? Are they on us? Are they under our skin?

The University of Arkansas at Fayetteville entomology department has a man on the case.

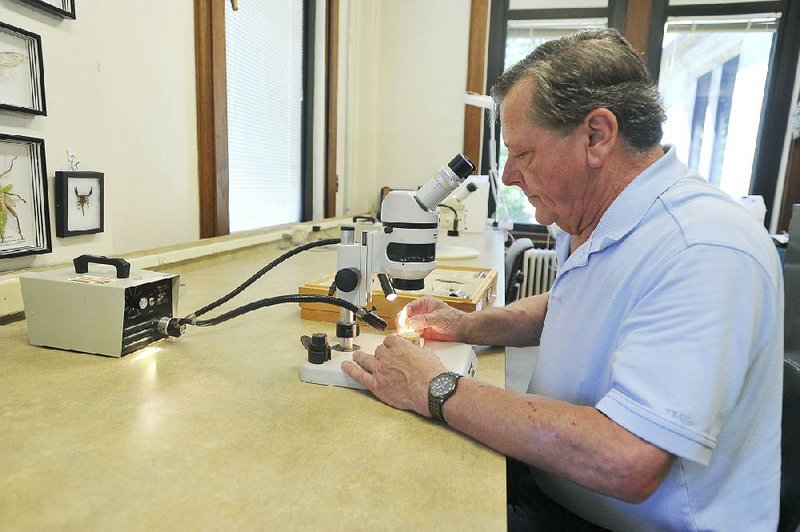

As part of his not necessarily quiet day-to-day duties curating the UA Arthropod Museum, Jeffrey K. Barnes, Ph.D., provides its Insect Identification Service.

This is not an underutilized service. Requests arrive frequently through a link on the museum's website, which can be viewed wherever the Internet is found; and yet they wax and wane, Barnes says.

"But right now things are heating up," he says. Because the season is heating up.

A sample of one June morning's clients:

• Someone associated with Eglin Air Force Base in Florida who has been studying the morphology of robber flies' eyes is preparing his research for publication and wants help labeling specimens.

• Someone who is very ill, about to be hospitalized, is seeking a home for her pet Madagascar hissing cockroaches.

• Someone from Virginia Commonwealth University wants to know how to find and collect caterpillar-killer Calosoma scrutator ground beetles.

Barnes is a published expert on robber flies, and so the military researcher is in luck. And he was able to give the Virginia grad student tips on using black light in a forest at night, where the adult and also the larval ground beetles may be climbing trees in search of caterpillars to kill.

But the pet owner? "What am I going to tell her?" Barnes asks. "I mean, if we took them here, they would just be dumped in with another living colony of Madagascar hissing cockroaches, and the pet value would no longer exist.

"But they'd be used. They'd be used for educational purposes."

With a huge reference library, a microscope, informed colleagues and 35 years of on-the-job training, Barnes often can identify submitted species on sight. For example, a recently received baggie containing 20 or so termites.

"I would not live in Arkansas without having a termite contract," he says. "Termites are an extreme problem here. It would very foolish to have a house without a contract."

But far too many clients he cannot help. The website link to his email address also spells out information he requires to make an ID: "where and when the insect was found, what it was doing, where it occurred, and why it is of interest to you." He also needs the client's name, address, telephone number and email address.

Also, the website says, "Do not send specimens taped to a piece of paper or tossed into a plastic bag."

"Most people ignore that," he says. "Usually they send me a bad photograph from their iPhone, and I often tell them, 'Your photograph is so terrible I can't tell.'"

Terrible comes at him in other forms as well.

"I have had bottles and bottles of human skin samples sent to me, along with nail clippers that were used to clip that bit of skin off."

Nail clippers ...?

"These people claim that they have worms or bugs crawling out of their skin," he says.

Parasitic infections can happen; for instance, there are chiggers. And it's possible to become home to a tapeworm by eating undercooked pork or to migratory screw-headed worms by eating badly handled sushi.

"Other people might feel that insects or related organisms are attacking them, when in fact they are having some sort of allergic reaction," he says. But also, there is "delusional parasitosis."

It's a species of human behavior encountered often enough by curators of arthropod collections that the Entomological Society of America once did a symposium on it. Barnes went to that and learned that "for the truly delusional cases, in which neither a medical doctor nor an entomologist can identify a cause, the professionals are in general agreement that methamphetamine abuse is the No. 1 cause."

Barnes estimates that once or twice a year he hears from delusional people.

One man dressed in full camouflage visited his office three times with skin samples. The third time he came with an ice chest of his skin "and other body parts." Barnes walked him out to the public lobby and suggested he see a psychiatrist. Not long afterward, this man was in the news, suspected in a shooting.

Does Barnes ever tip the police to his suspicions?

"Absolutely not. No no no no. I don't want to get that involved," he says. "And I try to avoid giving medical advice."

Insect identification is free (usually -- if people have a large number of specimens, he will charge a fee) and it is offered to all Arkansans. But he has received pleas for help from as far away as Italy and Singapore. Being unfamiliar with the fauna of those places, he refers such outliers to their local experts.

But most frequently he's contacted by worried homeowners confounded by the immature form of something common they would squish without a second thought in its adult stage.

So this insect ID service is an easy job?

"There haven't been too many that I haven't been able to nail down," he says. "But the problem is that there are an estimated 40,000 insects in Arkansas."

Forty thousand insect species, that is. People could mail in 40,000 individual insects, one at a time, and he might name them all -- without coming close to having seen it all.

More information about the museum, including its online photo gallery of common species and links to the identification service, is at uark.edu/ua/arthmuse.

ActiveStyle on 06/15/2015