At least four women with ties to Arkansas flew planes during World War II as members of the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). The program was established to fly noncombat military missions in the United States under the Army Air Corps so male pilots would be available to fly in combat overseas.

It's information that comes from the growing National WASP WWII Museum in Sweetwater, Texas, which opened in 2005. Construction on an expansion of the museum is set to begin soon.

"We have raised four million dollars through private funding and loans and are in the process of raising the last one million dollars," says museum administrator Carol C. Cain, adding that the museum has just signed a contract with its building contractor. "We hope to start construction in March or April."

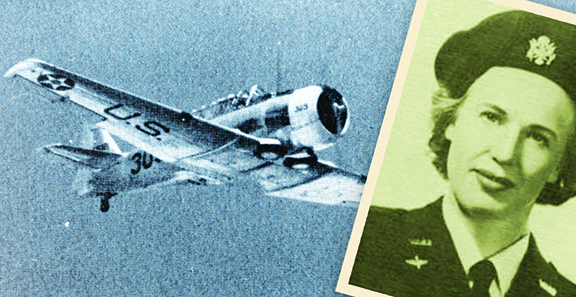

These female pilots, dubbed Fly Girls by the media, were the first women to fly this nation's military planes. In 1943, the Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS) and the Women's Flying Training Detachment (WFTD) merged to become WASP. About 25,000 young women applied to the program with 1,074 of them going on to successfully complete their training.

The female pilots served as test and instructor pilots, ferried and transported cargo (including parts for the atomic bomb) and personnel, simulated combat maneuvers, and flew every type of aircraft and every type of mission except combat.

And while an image created by Walt Disney similar to his studio's depiction of Peter Pan's Tinker Bell graced the cover of the women's class books, these pilots were brave beyond measure to sign up for this particular assignment.

Thirty-eight of the women died during their service.

"When the program closed in 1949, they all just went back home from where they'd originally come," Cain says. "They weren't considered a part of the military and had to pay their own way. Some of them had fallen so in love with flying, they became mail carriers, but the rest of them just dispersed and, because the program was no more, the only way they were able to stay in touch was through loosely organized social organizations, mainly in the areas near where they lived. One year a reunion might draw 300; another year maybe 500."

"That's one of the things that's so sad about this program. They just scattered to the wind."

There are 174 still living.

One Arkansan who served in the

program was Lea Ola McDonald, who

was killed during her first solo flight. McDonald was born in Hollywood, Ark., in 1921 but listed Seagraves, Texas, as her home she when joined the WASP program. She had earlier worked as a wing rigger for an aircraft factory in California. She entered training in Houston in January 1943 and graduated in April 1944. Assigned to Biggs Army Air Field with a tow target squadron, she flew B-24, B-26, AT-11, and C-45 planes. She was killed in June 1944 near El Paso, Texas, while flying an attack bomber during a practice flight. She was 22.

Others who identified themselves as Arkansans when they joined the program include Betty Fulbright, Dorothy Imogene Barnes, and Geraldine M. Tribble. What became of them?

Elizabeth "Betty" Fulbright White from Clarksville was in the last WASP class to graduate in December 1944. During her shortened service, she pulled targets for gunnery practice and transported cargo. After the war, she returned to Clarksville, where she married Omar White in December 1947. The couple worked as partners in the Western Arkansas Cold Storage Co., operating a refrigerated warehouse for frozen turkeys and broilers as well as storing fruit. Later in life, instead of flying, she and her husband took to the highways in the late 1970s on their Honda Gold Wing motorcycles with the Razorback Ramblers motorcycle club. White also fought breast cancer and underwent a mastectomy, according to her biographical file within the WASP collection ain the library of Texas Woman's University in Denton, Texas, which can be found online at wasp@twu.edu. She died in 1985.

Hot Springs native Dorothy Imogene Barnes graduated from the city's high school in 1935. While majoring in journalism at the University of Missouri at Columbia, she saw a notice on a bulletin board for a government-sponsored flying course, she explained in a newspaper article in October 1976. She enrolled in the class and grew to love flying. Shortly after graduating, she returned home to work for the Hot Springs Post and also acquired her commercial and instructor's licenses. When the newspaper folded, she became a flight instructor at the local airport.

Barnes joined the WASP program, she later said, because she had friends who were early WASP recruits and they encouraged her to join."I always believed we were doing something for the country," she said in the article. "We were there to supplement the men so more of them could go overseas."

She graduated from flight school in July 1943 and, as a WASP member assigned to Randolph Army Air Base in San Antonio, she flew the AT-6, a single-engine advanced trainer aircraft used to train fighter pilots, and the BT-13, a basic trainer flown by most American pilots during World War II and was in an intensive acrobatics course. After her unit was disbanded in December 1944, she returned to Hot Springs, where she spent more than 20 years working with National Abstract Co. She was still living in Hot Springs as of 2010. Her phone has since been disconnected, says Cain. As of press time, no further information about Barnes was known.

Geraldine Tribble, a native of Troy, became interested in flying because she had an older brother who was a flight instructor. He enrolled her in a civilian pilot training program he was teaching in Little Rock, and it was there that she earned her private pilot's license. She was listed in her class book as one of the class officers and a second lieutenant who served as a supply officer. She went into the WASP program in 1944 and, like Barnes, flew AT-6 and BT-13 aircraft. After deactivation, she obtained her commercial and instructor licenses and taught flying to veterans on the GI Bill.

Later in life, her name became Geraldine Vickers Crockett. In 2010, Congressional Gold Medals were presented to the surviving women and family members of those who had passed away. But Crockett, then 88, was suffering from Alzheimer's disease and living in an assisted living facility in Palm Springs, Calif., the Desert Sun newspaper reported at the time.

Her son Mike Vickers of Yucca Valley, Calif., accepted the honor on her behalf.

"We're real proud of her," he was quoted as saying then. "We never expected anything like this. I'm glad she's getting it. I just wish it would have come along sooner."

Vickers recently told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, "We took the medal out to her and showed it to her. And we still have it here with us." His mother passed away in February 2013. She was 92.

Peggy Vickers recalls a conversation she had with her mother-in-law: "I once asked her how she came to join the WASP. She told me her brothers were pilots -- she was part of a family in Arkansas known then as The Flying Tribbles -- and they told her about the program and that she should sign up for it."

After her service, flying remained a part of her life, Mike Vickers says: "She and my father, Robert M. Vickers, who was also a pilot, opened a crop-dusting business in California and also ran a flight school."

As late as the 1960s, his mother was still involved in flying. During that time, she was a member of a women's flying club known as the 99s and participated in a Powder Puff Derby in which the women flew from California to the East Coast. In her later years, she focused on social work, within the public school system in California and with individuals in their homes.

OVERDUE APPRECIATION

When the WASP program was deactivated in 1944, the files were sealed for more than 30 years and the women's service was forgotten, Cain says about the women who were paid less than men and received no benefits, adding, "These women didn't continue to leave a paper trail."

But in 1976, after the Air Force claimed 18 women in pilot school were the first women to fly military aircraft, "WASPs spoke up and these women rose up en masse, gathering their flight journals and log books from their moms' attics and in 1977 were granted militarization and won the right to some of the benefits their male counterparts received," Cain says, adding that in 1979, the women finally received veteran status.

The National WASP WWII Museum is in a circa 1929 hangar at Avenger Field where fire in the 1950s destroyed all of the other original structures there. Inside the hangar, artifacts including airplanes, engines, uniforms and more are displayed, while the official archives are housed in the library of Texas Woman's University in Denton.

The expansion of the museum will include a re-created tower at Avenger Field and additional floor space to display all of the artifacts donated by the women and their families in a permanent, climate-controlled exhibit space.

Style on 03/03/2015