The artist Brad Holland became interested in the art of telling tales while sitting at the knee of his Uncle Wayne in Arkansas. A spellbinding storyteller with scars across his back from fighting at Iwo Jima in World War II, Wayne Holland was a postman in the town of Greenwood in Sebastian County, where much of the Holland family has lived since the 1880s.

"Wayne was a fantastic storyteller," Holland says. "Whenever Wayne came to the house, I would listen to the way he told stories, and kind of pick up the rhythms, the way he would stretch stories out, pace stories. I wanted to write and draw, and I didn't know anybody who could tell a story better."

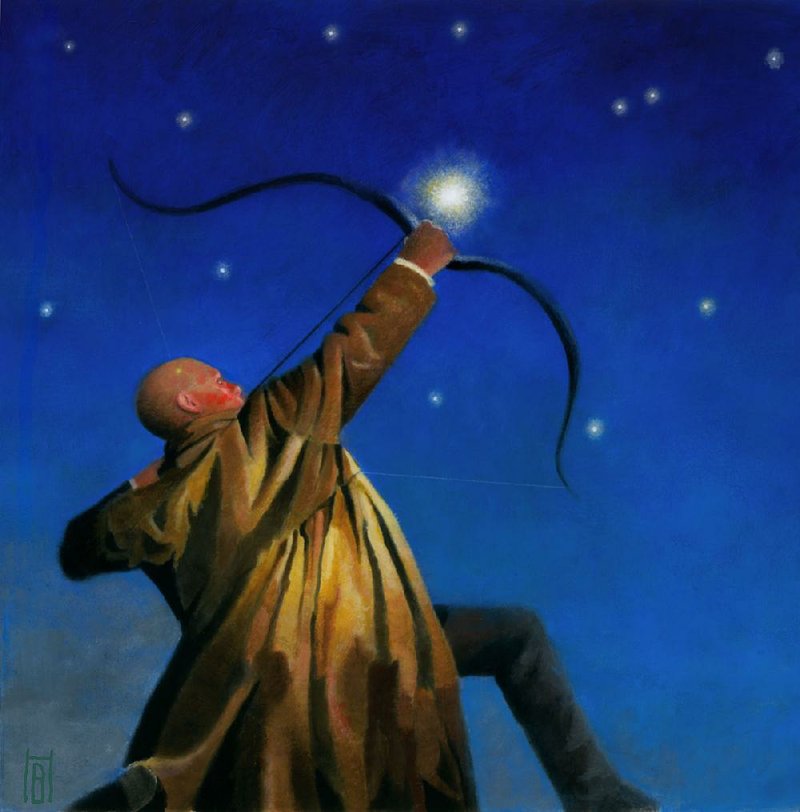

The time he spent listening to his uncle's stories deeply influenced the award-winning illustrator. Holland's dark and surreal imagery became a staple of The New York Times' Op-Ed pages, and appeared on the cover of Time and in virtually every other major magazine.

Holland, who still lives in New York, was born in Fremont, Ohio, just south of Lake Erie, in 1943. As a boy, he spent his summers with family in Greenwood. In 1960, his immediate family moved to Sebastian County, where he worked for his father building houses. At summer's end, he hopped on a bus for Chicago to pursue his dream of becoming an artist.

"I just figured I had to go someplace where there were artists and learn what they did for a living after I got there," he says.

MOVING TO THE MIDWEST

Before arriving in Chicago in 1960 at age 17, "that hotel in downtown Fort Smith was probably the tallest building I'd ever seen," Holland says. "I had never been to the big city, so I didn't know what to do, and I didn't know anybody."

He applied for jobs at each of Chicago's four newspapers, but he was rejected. He then did odd jobs before finding steady employment doing paste-up work for a catalog company. Two years later, he was hired by Hallmark and moved to Kansas City, Mo. At Hallmark, he illustrated books.

"I had a pretty good portfolio after two years," Holland says.

It was then that the signature style that made him famous began to emerge. "I was wandering around Kansas City one day and there was an old, antique wheelchair somebody had abandoned in a vacant lot, so I picked up the idea of an executioner sitting in a wheelchair. From there on, I just began doing images that just came to me.''

ARRIVING IN NEW YORK

In 1965, at age 22, Holland turned down a lucrative offer to work as an illustrator in Chicago and headed east. When he arrived at Grand Central Station, he called one of the premier art directors in New York, Herb Lubalin, who immediately commissioned him to do several illustrations. Lubalin told Holland, "You've got the most original portfolio I've seen in years."

The next day, he had a deal to illustrate two books for Doubleday.

With stunning speed, Holland was a working illustrator in New York. He checked into a hotel.

"If you've ever seen the movie Midnight Cowboy where Joe Buck gets a hotel room in Times Square, it might even have been the same hotel, because that's what my room looked like," Holland says.

At one point, he ran out of money. "I had a thousand dollars, but I left most of it in a bank in Kansas City," he says. "I was counting on the magazine that I was doing work for to pay me." He found himself locked out of his room and had no access to his mail, where the check was.

Holland lived on the streets for a week.

"I slept in the bus station and in some sculpture in Bryant Park .... Cops would come through with their nightsticks and bang on the sculpture, most of which was steel, that was serving as hotel rooms for homeless people. We would scatter like a bunch of roaches, heading out one side of Bryant Park and then circle around a few blocks, come back in on the other side and go back to sleep for another couple of hours."

Finally, "I had to bite the bullet," he says, and asked the magazine to cancel a check and write him a new one so that he could pay his hotel bill. "It was really quite embarrassing. You don't want to have to go to a client and say, 'Hey I've been living on the street for a week,' but I had no choice!"

A key ingredient in Holland's success was his work for Playboy magazine starting around 1967; he illustrated the Ribald Classics column for 25 years.

"Playboy put me on the map," Holland says. In a story on his website, BradHolland.net, he writes that "it was my good fortune to stumble into the magazine at just the right time, its reach was the greatest and its reputation the highest." After working for Playboy for a while, Holland writes, "I never had to show my portfolio again. Art directors called me."

OP-ED'S SIGNATURE VOICE

One door that opened for Holland in 1970 was particularly significant: the Op-Ed pages of The New York Times. He was brought into the Times by J.C. Suares. Holland has written that Suares "was the one who brought my drawings out of the world of men's magazines and ... into the mainstream." In the book All the Art That's Fit to Print (And Some That Wasn't), Jerelle Kraus wrote "Suares encountered an artist who became Op-Ed's signature voice."

"His work fit brilliantly into the Op-Ed pages of The New York Times," says Steven Heller, a prolific author of books on the graphic arts who writes the Visuals column for The New York Times Book Review. "It was a case of right place, right time."

When The New York Times nominated Holland for a Pulitzer Prize in the '70s, the nominating letter stated that his work goes "beyond the moment to illuminate a general condition universal in space and time. The images are sometimes brutal, but the feeling is almost always compassionate."

AN UNDISPUTED STAR

"Brad was the American exemplar of a style of conceptual illustration rooted in the idea," Heller says. In gauging his impact on today's illustrators, Heller believes that Holland is "a huge influence, whether they know it or not."

Suares gave a succinct description of Holland's work in a 1986 Washington Post article: "A little bit of surrealism. Always some strange, magical things going on, finding things where they don't belong, finding things smaller or bigger than they ought to be."

In the Post story, Holland was referred to as "an undisputed star of American illustration." The respected designer Roger Black, then art director at Newsweek, said in the story that "he's so popular now that he can pretty well control his own assignments. He doesn't take art direction, per se. He is willing to give you a few of his ideas. If you like them, cool. But he won't change something to make you happy."

A particularly iconic and controversial illustration came along in 1979. Holland was commissioned to illustrate Time magazine's Person of the Year, Iran's Ayatollah Khomeini. Holland's dark, brooding portrait captured the Iranian cleric's menacing presence perfectly.

Heller wrote the best summation of Holland's impact on his profession in Print Magazine when he opined that, "as [Jackson] Pollock redefined plastic art, Holland has radically changed the perception of illustration."

AN UNEXPECTED TURN

Two decades ago, his life took unexpected turns.

"I bought a big house in Connecticut, then I got divorced, gave the house away and then my mother got sick down in Arkansas. I had to put her in a nursing home," he says. Holland's mother died in 2004; his father in 1986. Both are buried in Fort Smith.

"I came out of that and we got into this fight [over copyright law]." Beginning in the 1990s, artists and illustrators faced a threat to ownership of their published work by the Internet and rise of stock image companies such as Corbis Corp. and Getty Images.

"So for the last 20 years, I haven't been doing what I wanted to be doing with my life, which is working on these big paintings. They're all sitting, most of them, half finished in a warehouse a few blocks from here."

Kraus writes about this in her 2009 book: "With a knowledge of intellectual property law deeper than most lawyers, [Holland] writes extensively on the subject, and is a founder of Illustrators' Partnership [of America], which advocated the continuation of existing copyright protection for freelance writers, photographers and artists in this tricky Internet age."

Holland says, "I got sued for copyright law and we fought that out in court for four years, and won. ... Of all the fights I have had in my life, that was the most damaging, in terms of what it cost me to fight it out."

THE ROAD BACK

Still, Holland continues to make art. He enjoys working for The Baffler (a magazine of art and criticism) and has his work on display at a gallery in Milan, where he is having a show this fall. He is also doing work for Playboy again. He also posts fairly regularly on Poor Bradford's Almanac, his blog on the website Drawger.com.

The artist is reluctant to discuss the high points of his career, noting, "The highlight of my career is getting back to all this stuff that I was doing before I got embroiled in all these copyright wars .... This show that I am having in Milan in the fall is, I hope, a road back to what I was trying to do back in the '90s when I got sidetracked in this fight over copyright and stock illustration, and all the damage that these people are really doing to art."

Holland sometimes thinks back on his days in Arkansas.

"The family runs pretty deep down there. My brother Lee lives in Van Buren, and my brother Jim lived in Fort Smith. [He] just died a few years ago. One of his daughters, Amalie, still lives there, so all of my immediate family is in Fort Smith these days.

"Arkansas keeps coming up in my life."

Style on 03/08/2015