A boxed set is like a little tomb, a way of finally categorizing and, ultimately, dismissing a given artist. You get several CDs and a lesson, all you need to carry forward.

Sometimes they seem superfluous and overreaching. Sometimes they seem inadequate. (How do you contain the Kinks on a book shelf?) Mostly it is safe to regard them cynically, as a method of corporate profit maximization. They prey on the completist and insecure -- those who need a totem to advertise their taste. In this age of what feels like (but isn't really) universal digitization and streaming services, they can seem archaic and unnecessary, conspicuous luxury items for the graying ponytail set.

So let's stipulate that not everyone will want or need Lead Belly: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection ($99.98), which bills itself as the first career-spanning boxed set dedicated to the Louisiana bluesman.

It consists of 108 tracks -- 16 previously unreleased -- spread over five CDs, along with a 40-page large-format book with historic photos and extensive liner notes by Jeff Place. (If you want to supplement this overview, consider the 96-track collection Lead Belly's Last Sessions, recorded in his New York apartment in 1948 by folklorist Frederic Ramsey and issued by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings in 1994.)

The new boxed set is handsome, but the best thing about it is it provides us with an occasion to talk about Lead Belly.

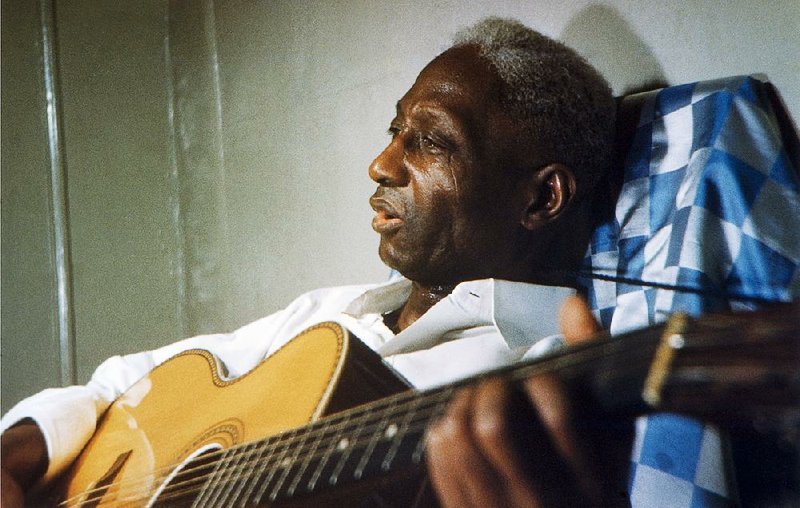

Start with the sound, the moan and sting of his 12-string guitar, a wobbling, low-frequency drone punctuated by throbbing bass runs and/or the knitting stab of syncopated arpeggios that hang like bloodied rags on barbed wire. It is too easy to call it "spooky." This tendency to turn our bluesmen into haints and wonders is reductive and unhelpful. Lead Belly was a man born Huddie William Ledbetter on Jan. 20, 1888; he was a technician as well as an artist.

What he did was get low -- his very heavy guitar's strings are slackened, 5 1/2 steps, so that the lowest and highest strings have been dropped from E to B, allowing him access to a muddy bottom denied most players, a register more often exploited by piano players. Lead Belly's lowest string was doubled by a string tuned two octaves higher; his second and third lowest (tuned to E and A, respectively) were paired with strings tuned an octave higher, while the two highest strings (F# and B) are tuned in unison with their twins.

This unusually low tuning -- a lot of 12-string players will drop down a step or two -- made Lead Belly's strings less tense, more playable, easier to fret and hammer. The architecture of the 1929 Stella 12-string he was famous for playing suited this technique. Its scale length was about an inch longer than standard, which kept the bass from getting too floppy, and allowed just a little more room between the frets to accommodate those big hands. The hands that, as Life magazine pointed out in 1937, "once killed a man."

Almost 100 years ago, with World War I winding down, three men were traveling together near New Boston, Texas. They were musicians and the sort of rough young men to whom bad things happen. Maybe the one who called himself Alex Griffin said something about a woman to the one who called himself Will Stafford. Maybe this made Stafford angry, and maybe the one who called himself Walter Boyd -- a guitar player of heavy build whose neck was ringed by a smile-shaped scar -- intervened.

The story I heard 30 years ago from Florida Combs, the singer's second cousin, was that Stafford went for his pistol and Boyd -- who was really Huddie Ledbetter of Mooringsport, La., using the alias after walking away from a chain gang-- shot him through the head.

What the court records say is that on Dec. 13, 1917, Boyd was charged with murder. He was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 30 years in prison. He was 33 years old. He would go on to be -- with the likely exception of Woody Guthrie -- the most influential American popular musician of the first half of the 20th century, a colossus who stands astride the confluence of blues and folk music and who made possible the folk revival of the early '60s.

What comes out more on the new Smithsonian set than on some other Lead Belly recordings is the man's prodigious musicality. He was something of a prodigy, mastering the rudiments of the keyboard by the time he was 8 by playing a single-key accordion called a "windjammer." Later he played some piano and organ and he learned guitar -- six-string at first ; the 12-string didn't come until later -- from men like Jim Fagin and Bud Coleman, who played in the brothels and on the streets of Shreveport's St. Paul's Bottoms. By the time he was 16, Ledbetter occasionally joined them, though he mostly played rural house dances and breakdowns (often with his cousin, Edmond "Son" Ledbetter, Florida Combs' father). Along with his battered guitar, he carried a Colt revolver.

No one denies he was sometimes surly and arrogant, although his family held that the story of how he came to be called "Lead Belly" -- that he was shotgunned by a Caddo Parish sheriff's deputy -- was apocryphal.

Given Ledbetter's subsequent place in American music, all the bad-man tales that adhere to his legend seem as superfluous and occluding as the static and dust on an old 78 rpm record. More important things than street fights happened on Shreveport's Fannin Street and in the Dallas district they call Deep Ellum. Those were the places where he heard the rolling barrel-house styles of piano men who used heavy, walking bass figures he'd later transpose to guitar to create a new vernacular for the instrument.

Yet the most important thing Ledbetter learned had nothing to do with technique and everything to do with giving voice to that inexpressible hurt called blues. His primary teacher was a fat, bland-looking blind man from about 80 miles south of Dallas. A man 10 years his junior, a man with an eerie, neck-prickling talent: Lemon Jefferson.

It may be nothing more than a chauvinism of the sighted, but it has often been implied that the blind are somehow "gifted" with an especially sensitive nature. While blind musicians -- especially if they are black men -- are often viewed, rather romantically and patronizingly, as savants, the overriding and overlooked reasons blind instrumentalists have played such a large part in shaping the blues are economic. Music is one occupational avenue the blind can pursue on almost equal footing. A blind boy was unable to work in the fields, and a poor blind boy was unable to lay up and be taken care of by his family.

When Ledbetter met Jefferson, the blind man was just another struggling street musician, too independent to allow himself to be led around, too mean to be partners with anyone for very long. But for a time before Ledbetter was sent away for manslaughter, the two played together in Dallas and Shreveport, in little town train stations, in dozens of anonymous and long-disappeared honky-tonks.

This was a crucial period of pollination. At the time, Ledbetter operated as a kind of human jukebox specializing in reels and ballads, the most popular music of his day. Jefferson scraped up against him with the blues and changed him. The faceless crowds who sat and drank or danced and sweated through the sets the men played may have guessed they were witnessing something rare. Jefferson's hands scampered over the fret board, echoing the high keen of his voice, in what must have been a marked contrast with Ledbetter's (then) warm tenor and accomplished playing.

In 1925, while at Shaw State Prison Farm, Ledbetter gave a command performance for Texas Gov. Pat Neff. A few months later, through coincidence or because he sang so well what the governor wanted to hear, Ledbetter was a free man. (People say he sang his way out of prison, but a lot of prisoners got early release that year.)

He moved back near his family home in Louisiana. He joined the church and drifted back into playing. But his repertoire had changed -- it had grown darker, bluesier. Along with the field hollers and work chants, he started writing evocative and terrifying originals like "Goodnight, Irene" (bowdlerized by the Weavers into a pop hit), and topical songs about personalities and historical events ("The Hindenburg Disaster," "The Bourgeois Blues").

If Jefferson gave him a voice for the blues, the prison farm gave him the heart for them.

For five years, he lived quietly. Then on Feb. 28, 1930, he was arrested for assault to commit murder. Within a few weeks, he was back in prison. Ledbetter was 41 and anonymous.

In 1933, the father-son folk archivists John and Alan Lomax, traveling the country making field recordings of folk singers for the Library of Congress, found Ledbetter in the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola.

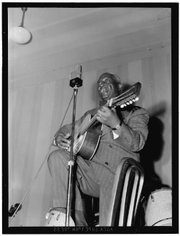

"We were amazed by his mastery of his great, green-painted 12-string guitar," Alan Lomax wrote. "We were deeply moved by the flawless tenor voice which rang out across the cotton field like a big sweet-toned trumpet. We believed 'Lead Belly' when he said, 'I'ze the king of all the 12-string guitar players in the world.'"

Legend has it that after recording dozens of original field hollers and work songs, Ledbetter asked the Lomaxes to take an acetate copy of one of his songs to Louisiana Gov. O.K. Allen. The song -- later copyrighted as "Governor O.K. Allen" -- asked, in no uncertain terms, for a commutation. While the Lomaxes claim they gave Allen a copy of the song, there is no real evidence he ever listened to it. Still, in 1934, Ledbetter was once again granted an early release from prison on the condition that he find a job. He wrote to John Lomax, asking for work.

Lomax later told the New York Herald Tribune about meeting Ledbetter after his release:

"On Aug. 1, Leadbelly [sic] got his pardon. On Sept. 1, I was sitting in a hotel in Texas when I felt a tap on my shoulder. I looked up and there was Leadbelly with his guitar, his knife and a sugar sack packed with all his earthly belongings. He said, 'Boss, I came here to be your man. I belong to you.'

"I said, 'Well, after all, I don't know you. You're a murderer. ... If someday you decide on some lonely road that you want my money and my car, don't use your knife on me. Just tell me and I'll give them to you. I have a wife and a child back home and they'd miss me."'

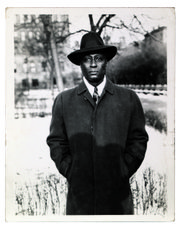

Lomax's version of events is suspect and no doubt self-serving. His interest at the time of the interview was establishing the burlesque act which Ledbetter's career was to become. Like Kong plucked from Skull Island, Ledbetter became "Lead Belly" -- a nickname his descendants disliked and say he hated -- and was displayed as a curiosity to the genteel citizens of New York. A tour of Northern colleges was arranged for the "Sweet Singer of the Swamplands." His criminal history was played up as a drawing card. Lomax called him a "natural" with "no idea of money, law or ethics ... possessed of virtually no self-restraint."

Yet as ugly and exploitative as this might sound today, we should remember the Lomaxes and Ledbetter were co-conspirators. Lead Belly became a celebrity, a minor don of Greenwich Village as he drifted into a supportive circle of mostly white folk performers including Guthrie, Pete Seeger and Cisco Houston.

Yet the legend was to be punctuated by violence once again. In 1939, he was arrested for assault with murderous intent. Two years on Rikers Island ruined his voice and broke his spirit. After his release, he split time between New York and Hollywood, recording dozens of inferior sides.

For years, most of the commercially available Lead Belly was bad Lead Belly -- mumbled recordings that made him sound like a man drowning in mud. He went on a tour of France in 1949 and was almost immediately hospitalized upon his return. He never left the hospital, dying on Dec. 6, a few months before the Weavers' version of Ledbetter's "Goodnight Irene" hit No. 1 spot on the charts.

To modern ears accustomed to airbrushed tones, Lead Belly can seem harsh and raw. There is a nervous, piercing quality to his voice when it climbs, the limits of the equipment of the day cloak the depth of his guitar playing. It's not the same as being there; we cannot know the past, but we might still be awed by pyramids.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

Style on 03/15/2015