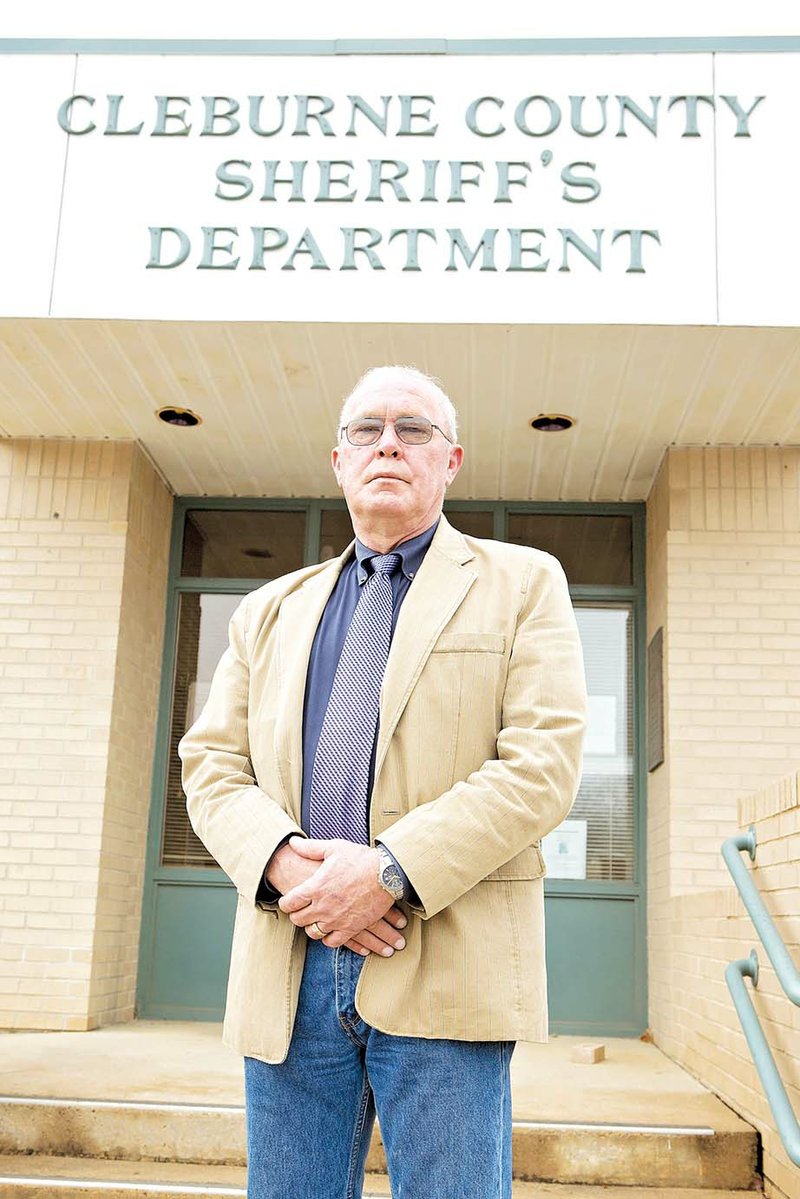

Cleburne County Sheriff Alan Roberson has killed two men during his 26-year tenure in law enforcement. He’s neither ashamed nor proud — it’s a somber possibility that comes with the job, he said.

In both incidents, which occurred a few years apart, the men had criminal histories and were on methamphetamine, Roberson said.

“Those two instances could have bothered me more,” Roberson said. “The ones I would probably have a lot more trouble dealing with would be a kid in a situation. When you’re dealing with convicted felons who are on drugs and have guns, and they’re 40 years old — you know what you’re doing. You put me in this position; you didn’t leave me a choice.”

Roberson’s philosophy is that a person has to do the right thing for the circumstances.

That’s why he’s served as sheriff twice.

The 60-year-old West Pangburn resident was chief deputy under Sheriff Marty Moss, who planned to retire and got another job, so he left office early. Roberson was then appointed to fill Moss’ unexpired term.

When Richard Swain won the election in November and took office Jan. 1, Swain asked Roberson to stay on as his chief deputy.

“Then the unimaginable happened,” Roberson said.

Swain, 68, who had previously had cancer, was hospitalized Jan 12 and died Jan. 25.

“I had a lot of respect for him. He would have made a good sheriff,” Roberson said.

It was the Cleburne County Quorum Court’s responsibility to appoint Swain’s successor. Roberson said he waited for a couple of days, and no one applied for the position, so he did. Three hours before the deadline, two other people applied.

“This is a job that needs to be done, and somebody has to do it,” Roberson said.

He’s not reluctant, just realistic.

“I’m about ready to retire anyway, so this is a good finish,” he said. “I’m honored. It’s easier to run a sheriff’s office when you don’t have to worry about elections.”

Roberson appointed veteran law enforcement officer Rich Houchin as his chief deputy. Houchin said he has known Roberson for many years.

“He’s just such a super guy; you couldn’t ask for a better guy to work for,” Houchin said. “He’s just such a calm, rational person, and sometimes that’s hard to find in a boss. The truth is, he’s just a really good person.”

Cleburne County Judge Jerry Holmes, who didn’t vote on whom to fill the sheriff’s post, said Roberson was a good choice.

“He’s been there several years and has been a good guy,” Holmes said.

“I’m not a total stranger to Cleburne County,” Roberson said. He said his mother, Jessie, was born in the former Shiloh community and attended a one-room schoolhouse in the county.

“I’m related to a lot of folks up here,” he said.

Roberson, who has one sister, grew up just outside Pleasant Plains, and his family had a Judsonia address.

“My dad had a service station, so I grew up washing windshields and fixing flats. That was back when you bought gas and never had to get out of your car,” he said. “It was before the days of convenience stores and you-serve.” When Roberson was about 14, his mother went to work at the hospital in Batesville, he said.

After Roberson graduated from Judsonia High School at 18, he enlisted in the Army when he was about to be drafted.

“I won the draft lottery in 1972 — only thing I’ve ever won in my life. I enlisted and spent 12 years in the military,” he said. “I was halfway through basic training when Nixon … decided to pull troops out of Vietnam,” Roberson said.

Roberson was stationed in Europe, Texas and Maryland.

“I loved Europe. For a country boy from Arkansas, that was educational. I lived just outside Frankfurt. I enjoyed it; you see other cultures. I think it’s good to get out and see how everything else really works and to understand we’re not the only society and culture on the planet.”

Part of the time, he served in vehicle maintenance in the military. With skills he’d honed in the Army, he worked as a mechanic when he came back to Judsonia.

“How I ended up in law enforcement is kind of …” — Roberson paused and sighed — “I guess everybody has a story. We lived outside of Pleasant Plains out about the county line — my parents lived there. I had gotten out of the Army. Our house was up on a little bluff with a creek at the bottom of it — across the creek was an old house and rental property.” Somebody probably rented the house “and decided to plant marijuana plants up and down the creek.”

Roberson said his father kept asking, “What are they doing down there?” Roberson investigated and found little plants. “I didn’t figure this was chili peppers,” he said, laughing.

Roberson reported the marijuana to the chief of police.

“Also at the time, we lived next door to the chief of police in Judsonia. We weren’t good friends; it was just a coincidence,” Roberson said. “We got to talking, hanging around some, and the next thing I knew, I was in the [police department] auxiliary.”

“It was fascinating,” he said. It’s not like cop shows on television, though, he said. “It’s probably fascinating for everybody at first. You eventually find out it’s not what you came to expect from it.

“Law enforcement is not really paramilitary. I wouldn’t go that far. It’s similar to the military in that it’s structured and organized. After 12 years [in the military], I was comfortable with that.”

After a long stint with the Judsonia Police Department, Roberson was hired by the Prairie County Sheriff’s Office in Des Arc, and he realized he liked working in sheriff’s offices.

“I’d never go to a municipal agency again, especially in a smaller town; it’s just too confining,” he said. “You just have more room in the county.”

He joined the Cleburne County Sheriff’s Office in 2002.

His first job for the sheriff’s office was as a deputy for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers during the tourist season. It’s a unique position, Roberson said. Every year, the Corps of Engineers contracts with the Cleburne County Sheriff’s Office to provide four full-time deputies for law enforcement in 11 federal recreation areas, Roberson said. After that position, he moved into a regular full-time deputy slot and continued to be promoted.

With the unexpected death of Swain, he stepped into the leadership role again.

“Being sheriff is an honor and a privilege,” he said. “Being appointed sheriff is not the same as being elected. People have the right to elect a sheriff. … I take being it with a grain of salt. You still have the responsibility. I greatly respect the right of the people to select their sheriff.”

Roberson said his philosophy is to see the big picture, not get focused on just one problem, such as drugs.

“Everything goes together. … You have to use caution on getting fixated on this one problem: ‘Meth creates all my problems,’” for example, he said. “Probably one of the biggest challenges for a sheriff is balance. You have to balance what resources you have available with the biggest problem you have at the moment, and it changes. Suddenly, you have thefts pick up; you have to focus on that. You have to keep a broad view of everything going on in your county.

“The biggest issue for a sheriff is the county jail.” The Cleburne County Jail is “overcrowded — too many state inmates. We’re not getting paid like I think we should by the state for holding their state inmates.”

Roberson said he gets a daily headcount on how many people are in jail. On March 4, he said, there were 70 in jail, and 22 were state inmates.

“Basically, a third of my jail is tied up for people who have been to court and been sentenced,” he said.

A community-service work-release program placed under the direction of the county road department helps, he said. When offenders have fines they can’t pay, they perform work, like picking up trash.

“You get something back from them and save the expense of the jail,” Roberson said.

As in any law enforcement job, the possibility of being injured or killed — or having to use a weapon on someone — is a real possibility.

“I think if you’re going to be in the military — and that’s where it started — you just kind of accept the possibility, or in the military the probability, of having to do that. You understand it; you cope with it. That’s part of it,” he said.

Roberson has faced that reality twice in his career, once in 2005 or 2006, he said, and the second time in 2008.

In the first incident, Roberson was involved in the traffic pursuit of a suspect. When Roberson cornered the man and tried to arrest him, “he got ahold of my gun,” Roberson said.

Roberson said he and the man scuffled, and Roberson shot the man.

“I don’t have second thoughts about what happened; it was justified,” Roberson said. “He had a complete meth lab in the trunk of his car and was a multiconvicted felon.”

After two days on leave, Roberson was cleared to come back to work.

“Honestly, if somebody gets in a situation where they kill somebody, they need a couple of days. They may not think they do,” he said.

The second incident was more dramatic.

Roberson responded to a call at about 8 a.m. for an incident north of Greers Ferry. A man had gone to his mother’s house and was chasing her and shooting at her; then he set his mother’s house on fire.

Roberson arrived about the same time as the Greers Ferry Police Department, he said. The man was driving onto Arkansas 225 from a gravel road, and officers cut him off.

“We had the road blocked. He stopped; we stopped. Everybody steps out of their car and looks at each other. He raised his gun and started shooting,” Roberson said.

He said the man was about 15 feet from him, sitting in his truck.

“He emptied his gun through his windshield at me; I shot back,” Roberson said.

He had the door of his patrol car open and was taking cover behind it, he said. After he shot the suspect, the man’s truck hit Roberson’s car and started pushing it back. An Arkansas State Police investigator told Roberson it was probably “muscle memory” that caused the man to floor the gas, sending the truck into Roberson’s vehicle.

“I’m standing behind the door, being drug back and shooting,” Roberson said. Within a few seconds, it was over, and the man was dead.

Roberson knows he also could have died. “He missed,” Roberson said, simply. He said the suspect was shooting a .38-caliber Special with round-nosed ammunition at the windshield. “Those are notorious for deflecting. Or, maybe he was just a lousy shot and missed,” Roberson said.

Roberson is a firearms instructor in addition to being sheriff.

“One of the first things I do when I teach the firearms class, especially with new people, is get on my soapbox, so to speak. Cops, especially — guns are like boy toys. Everybody wants to talk about what kind of bullets do I want? What kind of gun do I want? The first thing I try to explain to them is tell them the most serious thing an officer does is carry a weapon. Regardless of the circumstances, and regardless of what a person is doing or has done, if they think taking a human life is easy, or fun, I don’t need them.

“It’s something I look for in people we hire — how I think they will react under extreme stress, when you get a very, very short time to do something, and you’d better be right,” he said.

“In a very broad sense, what the Sheriff’s Office has to do is one, keep the county safe, and as good as it can be, but at the same time, it’s almost as important that you make sure in doing it, you create an atmosphere and do things that make people feel secure and safe. They have to see patrol cars; they have to know you’re there. We check businesses and put cards on the door; they know they’re being checked.

“It’s a good county,” he said. “We have a very low crime rate. No place in the world is perfect anymore, but we’re better than a lot of places.”

And Roberson intends to keep it that way.

Senior writer Tammy Keith can be reached at (501) 327-0370 or tkeith@arkansasonline.com.