The Civil War ended 150 years ago. Its ghosts linger on aluminum.

Scattered across the state, 113 aluminum plates, new historical markers erected in or planned for 62 counties, convey in 533 characters an event to be remembered.

Old times here should not be forgotten. Because they're unforgivably grim.

Old times such as:

How the Civil War almost started in Little Rock.

How a steamboat disaster on the Mississippi River killed about 1,800 people.

How soldiers of the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry were slain in Ouachita County as they lay wounded on the battlefield.

Where to begin? With Mark Christ of the state's Historic Preservation Program. From his office in downtown Little Rock he can visualize a marker very nearby. It's underneath the Main Street Bridge, where the C.S.S. Pontchartrain once docked on the north shore of the Arkansas River. The ship was burned when Little Rock fell to Union forces in 1863. One of its cannons is now in the front yard of the Old State House.

Like the river, we meander. It's easy to do.

The markers come by way of the Arkansas Civil War Sesquicentennial Commission, created by the Arkansas Legislature in 2007. The Historic Preservation Program has plugged along since, working with local organizations to get at least one marker in every county.

Thirteen counties are without. They are Bradley, Calhoun, Crawford, Franklin, Hot Spring, Howard, Lafayette, Lawrence, Montgomery, Newton, Polk, Sevier and Sharp.

The commission goes out of business on Dec. 31. Christ said he's cautiously optimistic those counties will generate local sponsorship for markers by then.

Markers are made by Sewah Studios in Marietta, Ohio. Their manufacture supports the idea that the past isn't dead, it isn't even past -- Sewah Studios made historical markers for the Civil War centennial 50 years ago. Christ called that "a spirit of continuity."

Thirteen lines of 41 characters each isn't much, but perhaps is right for the age of Twitter.

"I prefer to think of it as haiku," Christ said.

HISTORICAL HAIKU

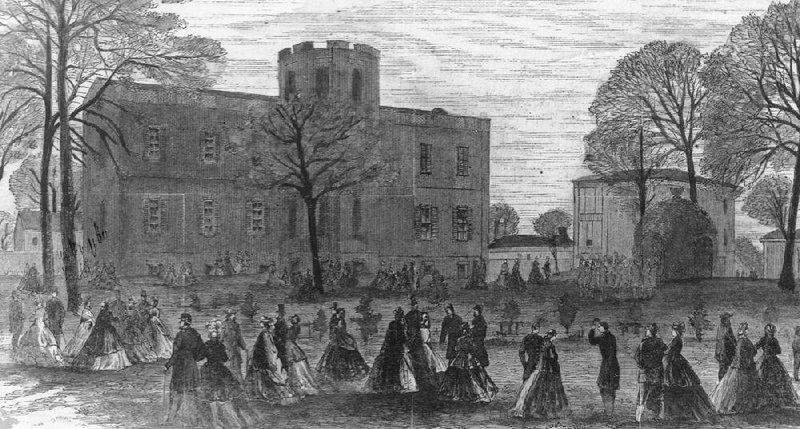

The first historical haiku was erected in 2011 behind the MacArthur Museum of Arkansas Military History near downtown Little Rock. It's titled "The Arsenal Crisis."

Could this crisis in February 1861, two months before Fort Sumter was fired on, have precipitated the outbreak of hostilities, and thus changed the history of Arkansas?

"It's what we as historians love to speculate about," said

Stephan McAteer, executive director of the MacArthur Museum.

"If events had turned out differently we would be reading in our history books today that Little Rock was where the Civil War started rather than Fort Sumter."

The hero of this tale is U.S. Army Capt. James Totten. Briefly -- but not quite as briefly as the marker -- this is how the crisis played out.

Totten and about 75 of his soldiers occupied the arsenal, built in 1840, but which for many years was not garrisoned with such a force. Totten occupied the place in December 1860.

Rumor and speculation ran wild in Little Rock, then a city of about 4,000 people.

"Why after all these years, when there was just a caretaker, are they sending soldiers to the arsenal?" McAteer said.

Perhaps because of the munitions. Gunpowder. Artillery shells. Cannon balls. Rifles.

"It was a very prized possession to have, whether you were fighting for the Union or for the Confederacy."

News of the troops was disseminated by a newly completed wonder of the age -- a telegraph line. And up to 1,000 militia from southeast Arkansas, "the hotbed of secession," came to Little Rock.

"Armed, armed," McAteer said. "The fact was these were civilians. Rowdy might be a good way to describe them."

Rumors were that 4,000 to 5,000 more of those rowdies would come.

Totten sent telegrams to Washington, where James Buchanan was still president. (Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated in March. Presidents are now inaugurated in January.) No response.

"Totten was in a pickle."

After five tense days, the captain relinquished the arsenal. The federal troops were allowed to go to the river and leave the state.

The ladies of Little Rock showed their appreciation by giving Totten a sword.

"They were so pleased that by his bravery we had avoided what they called an effusion of war."

Little Rock's ladies were later displeased when Totten fought for the Union at Wilson's Creek in Missouri.

WORST MARITIME DISASTER

A close examination of the marker The Sultana Tragedy shows it has only 12 lines. That's not much for America's worst maritime disaster.

The riverboat Sultana was steaming north on the Mississippi River on April 27, 1865. It was dangerously overloaded with about 2,200 passengers. Most of them were freed Union prisoners of war from the Andersonville and Cahaba POW camps in Georgia and Alabama, respectively.

A boiler exploded at 2 a.m. when the ship was about seven miles north of Memphis.

An entry in the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture, written by Nancy Hendricks of Arkansas State University, has this description.

"Men who had been sleeping suddenly found themselves immersed in the cold waters of the swollen river. Many were killed instantly by the explosion, fire, falling timbers, shrapnel and searing steam from the boilers, as well as by drowning. Reports estimate the number of dead as high as 1,800, with hundreds of bodies floating in the river when Memphians awoke the next morning."

Men from Marion were among those who tried to save passengers, notes the marker.

"The connections between then and now are still resonating," Christ said.

One of those rescuers, John Fogleman, was a relative of Frank Fogleman, now in his sixth term as mayor of Marion.

"Boating accidents were common at the time," Fogleman said. "It probably didn't draw the attention it deserved by its magnitude."

Hendricks concurs in her encyclopedia entry.

"More people died in the sinking of the riverboat Sultana than on the Titanic. However, for a nation that had just emerged from war and was still reeling from the assassination of President Lincoln, the estimated loss of up to 1,800 soldiers returning home on the Mississippi River was scarcely covered in the national news."

Harper's Weekly did produce an illustration of the Sultana in its edition of May 1865. The double-masted steamboat is in flames, the river's surface covered with the desperate and the dying.

FORT PILLOW MASSACRE

Much of memory is timing, as the Sultana shows. Another example is the atrocity that befell the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry at Poison Spring, Ouachita County, on April 18, 1864, six days after what became known as the Fort Pillow Massacre.

A division of 2,500 Confederate cavalry under Nathan Bedford Forrest attacked the Union garrison at Fort Pillow, Tenn., 40 miles north of Memphis. About half of the 600-man garrison was made up of black soldiers, most of them former slaves. When Forrest's men swept into the fort, they pursued and slew the blacks. Of the 262 black soldiers in the fort, 62 survived.

What else survives is the stain on Forrest's reputation.

What survives in Poison Spring is memory and a Civil War sesquicentennial marker put up in 2011, one of whose sponsors is the Zion Hill Human Services Agency.

The 1st Kansas was a regiment that included many former Arkansas slaves. Formed in August 1862, it was the first black unit recruited during the war. The regiment engaged in combat at Island Mound, Mo., and Cabin Creek and Honey Springs in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) before Poison Spring.

It lost 117 in battle at Poison Spring, says the marker, and "many men were slain as they lay wounded after the battle, killed by Confederate troops."

The engagement at Poison Spring was part of the Camden Expedition by the Union Gen. Frederick Steele, whose army went from Little Rock to Camden in the spring of 1864.

The campaign, Christ said, was "a cornucopia of awfulness."

'MURDERED ON THE SPOT'

Mary Jane Warde's 2013 book published by the University of Arkansas press, When the Wolf Came, The Civil War and the Indian Territory, includes a writing from Col. James M. Williams, commander of the Union column, about the 1st Kansas.

"Many wounded fell into the hands of the enemy, and I have the most positive assurances from eye witnesses that they were murdered on the spot."

Both white and Choctaw Confederates took part. An officer from Texas wrote in his journal that he saw at least 40 bodies "in all conceivable attitudes, some scalped & near all stripped by the bloodthirsty Choctaws."

The awfulness continued two weeks later at Jenkins Ferry, when soldiers of the 2nd Kansas Colored Volunteers killed or wounded surrendering Confederates, shouting, "Remember Poison Spring!"

Chester Thompson of the Zion Hill Human Services Agency is also Bishop Thompson of Zion Hill Baptist Church in Camden. A member with an interest in local history generated wider interest in the Battle of Poison Spring, he said, and the human services agency raised money for the marker and flag pole.

"We had a thing, a reconciliation thing," Thompson said. "We had white people and black people and native Americans to come and we had a service at the state park. We remembered those soldiers and we did some things to bring closure. It was a horrific thing to happen to African-Americans."

Last year's re-enactment at Poison Spring State Park was the first in 20 years to feature black re-enactors, Thompson said.

Something else is in the works, he said.

"Plans are to build a real big memorial with names of the soldiers on it," he said.

"Nobody really knew what actually happened," Thompson added. "This brought it all out. And people were able to move past it."

The locations of the Civil War sesquicentennial markers can be found at arkansascivilwar150.com.

Style on 03/29/2015