Americans have been avid consumers of biography at least since Mason L. Weems' The Life of Washington was a best-seller in 1806.

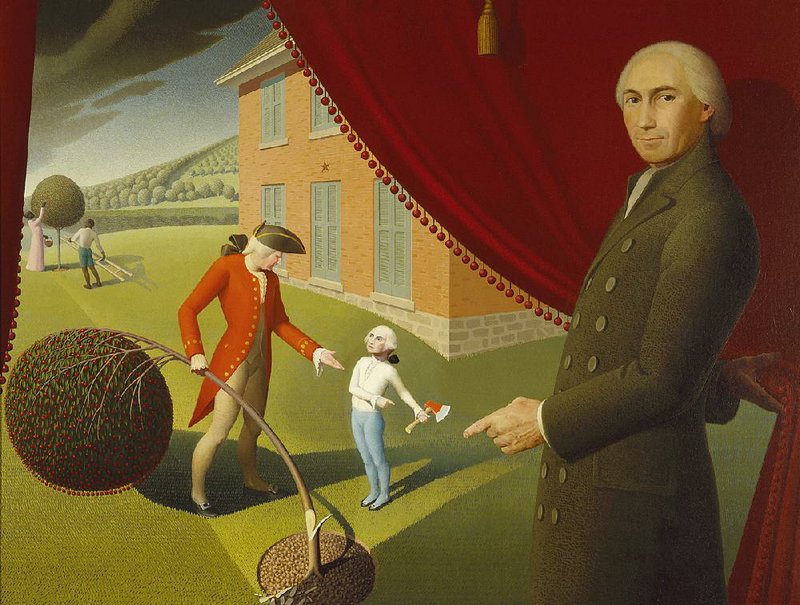

If you have heard of Parson Weems' book at all, that's likely because it's the source of most of the apocryphal legends that surround the young Washington, including the famous story of his chopping down his father's favorite cherry tree that ends with George gallantly confessing to arborcide: "I can't tell a lie, Pa; you know I can't tell a lie. I did cut it with my hatchet."

Any 21st-century reader who takes on Weems' book is likely to find it risible, full of florid language that depicts Washington as "the hero, and the Demigod ... 'the Jupiter Conservator' ... friend and benefactor of men."

Some of Weems' contemporaries thought it was a little over the top: "We have questioned whether the book before us may not be termed a novel founded on fact," a Dr. Bigelow reported to the Anthology Society of Boston in 1810, allowing that Weems "often transports us from a strain of religious moralizing ... to the low cant and balderdash of the drinking table."

The story was picked up by the popular textbook McGuffey Reader and thus became embedded in the imaginations of 19th-century schoolchildren and hence the culture. More serious-minded biographers either ignored the legend or attacked it. In his 1896 book George Washington: A Profile, future president Woodrow Wilson wrote there was "no evidence whatever" that the anecdote was true. In 1904, Joseph Rodman published an essay in The Critic magazine that called the incident "idle quip and irreverent jest."

Things got worse for Weems. In his The Life of George Washington (1920), Henry Cabot Lodge said Weems' once popular book would never have been found in "the hands of the polite society of the great eastern towns" and suggested its "tawdry style" appealed only to the unlettered "backwoodsman." William Roscoe Thayer wrote in George Washington (1922) that "owing to the pernicious drivel of the Reverend Weems no other great man in history has had to live down such a mass of absurdities and deliberate false inventions." In 1926, Rupert Hughes, in George Washington, the Human Being, The Hero, alleged that because little was known about Washington's childhood, Weems filled it out with a "slush of plagiarism and piety."

On the other hand, Weems claimed to have a source for the cherry-tree anecdote (which he asserted was "too valuable to be lost, and too true to be doubted"). He said he heard the story from an "aged lady" who described herself as a cousin of Washington's. And there were cherry trees on the property where young Washington grew up. Weems' story never says the tree was chopped down, it says it "was barked." And, as blogger/historian/screenwriter Carl Anthony pointed out online in 2012 (tinyurl.com/cbznh4p), there's strong evidence that Weems couldn't have invented the story of Washington and the cherry tree because the story had been around at least since Washington's presidency.

It's impossible to prove that all the facts of the story are true. We can't know the details of any conversation between Washington and his father, we can't know whether his father rejoiced when his son admitted hacking at the tree with his new hatchet -- but maybe we can agree to leave poor Parson Weems alone. He was a preacher, not a historian; his methods were journalistic. He interviewed people, he didn't study documents. And he had access to a lot of people who knew Washington, even, as Anthony points out, Washington himself. He didn't invent the fable -- at worst, he presented a fable as true, attributing it to a vague source. In his book the story is a long quotation; he might have pruned and prettied the speaker's actual words, he might have made them up, but we don't know that. It's at least possible that the cherry tree story is substantially true.

...

"Unfortunately, I'm afraid all biographies and autobiographies are fiction," The New Yorker's Joseph Mitchell told literary critic Norman Sims in 1989.

The quotation comes from Thomas Kunkel's Man in Profile: Joseph Mitchell of The New Yorker (Random House, $30), a deeply interesting if intermittently frustrating attempt at explaining the enigmatic writer, who went from being a prolific and especially graceful chronicler of uncelebrated lives to a cautionary tale. For the last 32 years of his long career at The New Yorker, from 1964 until 1996, Mitchell failed to publish a single word.

This fact sadly obscures the quiet power of his work. Mitchell was especially adept at imbuing the denizens of low quarters with dignity no matter how bizarre they might initially appear. His 1940 portrait of Jane Barnell, who, as "Lady Olga Roderick" appeared in Tod Browning's 1932 film Freaks and worked as a circus bearded lady, all the while pining for a kind of domestic banality (she practiced shorthand as a hobby and dreamed of "becoming a stenographer the way some women dream about Hollywood"), is a master class in how to build a world from simple, declarative sentences -- from the patient setting of fact upon fact. It resolves in a beautiful, offhand quote from the subject: "If the truth be known, we're all freaks together."

At the time, Mitchell may have understood that his ultimate legacy was to be seen as a kind of freak. These days his reputation as a writer's writer has been obscured by the barrenness of his life's second act. For his last 32 years at the magazine, Mitchell dutifully came into the office each day to think and maybe type a little. Though he was treated with tenderness by his editors, particularly by William Shawn, who had known Mitchell since they were both hired by the magazine in 1938, he never overcame his debilitating block.

Those looking to Kunkel's book for revelation are likely to be disappointed. As it turns out, Mitchell was trying to write a memoir that toggled back and forth between his childhood in North Carolina and his days in New York. He had an idea about profiling Ann Honeycutt, who had beguiled several male writers at the magazine. He thought about a history of McSorley's Saloon, told via the succession of Irish families who had owned the New York landmark. He wanted to write about Joe Cantalupo, the informal mayor of the Fulton Fish Market. Yet he never did.

Kunkel is industrious and thorough; not everything he uncovers burnishes Mitchell's legend. The conventions of journalism were somewhat looser in the days when he was productive. It's not surprising to learn that his quotations were often massaged and some of his characters were composites. Years after his piece profiling him ran, Mitchell publicly admitted a figure in several of his stories, Hugh G. Flood, "a retired house-wrecking contractor, aged ninety-four," was a composite of several old men who used to hang around the Fulton Fish Market. But Kunkel reveals that he wasn't Mitchell's only invented character. In a 1961 letter to the magazine's attorney, Mitchell admitted another subject of one of his famous profiles was a composite: "Insofar as the principal character is concerned, the gypsy king himself, it is a work of imagination," Mitchell wrote, "Cockeye Johnny Nikanov does not exist in real life and never did."

Kunkel suggests, with some authority, that a lot of Mitchell's writing was really about some version of himself -- that he often expressed his own thoughts through words he lent his characters. With some empathy, Kunkel suggests that much of this is forgivable, especially when one considers the expectations of Mitchell's readers and the virtues of the essays themselves. Kunkel quotes Mitchell's friend, critic Philip Hamburger, who called the Flood pieces "fiction of the highest order":

"Mitchell was projecting himself fictionally into old age, and it's a masterpiece. There are no two ways about it. And I don't think that it makes a bit of difference whether there was a Mr. Flood or there wasn't a Mr. Flood. Just as it doesn't make a difference whether there was a Nicholas Nickleby or a David Copperfield.'"

Mitchell was trying to arrive at a higher order of truth than journalism allows. If that sounds like the sort of high-minded evasion a plagiarist might make, well, it's also what all poets try to do.

What's sad about Mitchell's writing block is that it didn't seem to prevent him from writing -- it prevented him from finishing. He reached a place where there were no deadlines and nothing so concentrates the mind as a deadline. They're invaluable to some writers for they remind us of the finite nature of the pursuit. At some point, you simply give up and pass the copy along. Otherwise you don't get paid. Mitchell published 14 stories in 1939, his first year at The New Yorker, the same number he'd publish over his next 56 years there.

Toward the end, he was known to bemoan his situation, to wish aloud his editors would just fire him so he might go home to North Carolina. Had they done so, in the 1970s, maybe Mitchell, forced with the need to make a living, or maybe driven by an urge to avenge himself, would have recovered his bearing and finished his memoir and written much more.

And we would would remember him more as a writer than as an enigma.

But Kunkel gives Hamburger the almost last word. On the penultimate page of the book, he addresses the fundamental question:

"Why didn't he write more? Well, he wrote enough."

...

Speaking of finite limits, we're left to just mention some other recently published biographies and autobiographies. The Life of Saul Bellow: To Fame and Fortune by Zachary Leader (Knopf, $40) is a fact-heavy account of the first 49 years of the novelist's life, taking us from his first memories of Quebec through the publication of his commercial breakout Herzog in 1964. Leader is thorough and balanced, perhaps to a fault. While we learn plenty about Bellow and his incident-rich life, Leader's book lacks the fire and crackling readability of James Atlas' 2000 biography Bellow, an ambitious and controversial work that at times seemed to revel in the hypocrisies apparent in Bellow's private life and his nasty prejudices. Leader has done all right, and I await the second volume which ought to be more fun. I just wish he weren't so judicious. Bellow deserves, if nothing else, passion.

Also just published is It's a Long Story: My Life by Willie Nelson and David Ritz (Little Brown, $30). This is Nelson's second autobiography -- after the superlative 1988 Willie, co-written with the late Bud Shrake -- and it's a highly readable if slight work that finds a breezy tone early and never even pretends to get at anything genuinely interesting. There are plenty of hand-smoothed facts here, but you'll find more truth in any number of the guy's recordings.

Much, much better is Oliver Sacks' poignant and uplifting memoir On the Move: A Life (Knopf, $27.95), which thrillingly communicates his love of the world and his wonder at the variety of human experience. Sacks announced he was dying of liver cancer in an essay in The New York Times in February and this book, in which he turns his remarkable analytic and descriptive powers on himself serves as a generous benediction, a beautiful parting gift. Sacks' life has been as full of incident as Bellow's or Nelson's, and he's able, through his twin gifts for science and literature, to persuade us of the value of the journey, that brief and wondrous interval when we are alive in the world.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

Style on 05/10/2015