It might be impossible to overstate the importance of Mystery Train, but that doesn't mean people haven't tried.

"The 1975 appearance of Greil Marcus' first book ... was an explosion as unexpected and indelible as the first records Elvis Presley had cut almost exactly 20 years before," Mark Rozzo wrote in the Los Angeles Times' Book Review. Alan Light, writing in The New York Times Book Review, called it "perhaps the finest book ever written about pop music." Bruce Springsteen said it got "as close to the heart and soul of America and American music as the best of rock 'n' roll."

They're all right. If Mystery Train didn't change my life, it at least diverted it, making me aware of new modes of thinking about products meant as entertainment.

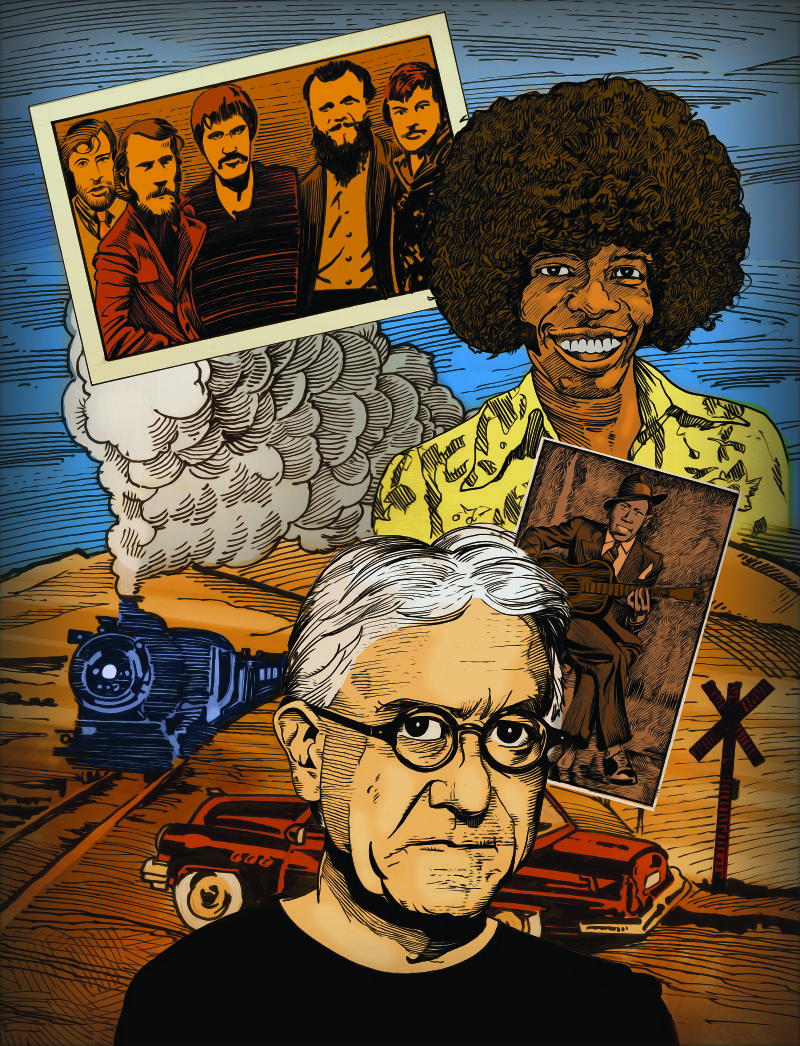

At first glance, it seems simple enough -- it consists primarily of essays on six key figures in American rock 'n' roll history: Robert Johnson, Harmonica Frank, Randy Newman, The Band, Sly Stone and Elvis Presley. It's an ambitious synthesis of musicology and biography that becomes a kind of map of the American soul, an alternate narrative about how we arrived at where we are today. Mystery Train is an investigation, a spiritual procedural that carries a faint lantern deep into America's dark heart.

Our country wouldn't be the same place without the book. Johnson was largely unknown when it was first published. Marcus noticed things about The Band, Stone and Newman that invited reconsideration.

Maybe most importantly, Mystery Train is largely responsible for the rehabilitation of Presley's artistic reputation. But in 1974, he was a joke to most of us.

Marcus argues that it was impossible for Elvis to do anything other than what he did, that the fact of his

existence -- his enormous fame -- obscured and made moot any attempt to connect to his audience in the ways of normal artists. The apotheosis of Presley made it impossible for him to function in any authentically human way. He was trapped in his own image.

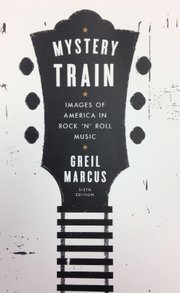

There's a new sixth edition of Mystery Train (Plume, $17) out, which allows us to renew acquaintance with the book and ask Marcus a few questions via email.

...

Q. While I've read critics like James Agee, Edmund Wilson and Manny Farber, I only came to them after being exposed to your work. I can't say Mystery Train made me want to become a writer -- that was probably The Great Gatsby -- but it made me want to become a certain kind of writer. Is there a book that is for you what Mystery Train has been for generations of people like myself?

A. It was and is Pauline Kael's I Lost It at the Movies. When Artforum was doing a special issue on works of art that had most deeply affected various writers, I chose that .... Her presence in my life has been a constant since I read her first book in I think 1966. That we later became friends is part of it -- but I never met Edmund Wilson, and he's been a constant as well. And Fitzgerald, too.

We became friends after I reviewed Reeling in Rolling Stone and after making clear that I thought of her as a great writer and why, went on to complain about her writing, her hyperbole and a certain insecurity in her style as covered up by noise. She called me up and said, "This is Pauline Kael. Did you really mean all those things you said about me?"

I thought, "what am I supposed to say, 'No, I just did it to call attention to myself?'" I said, "Yes." She said, "Well, my daughter agrees with you, but I don't. I'm coming to Berkeley next month and I'd like to meet you."

Pieces on the order of "The Glamour of Delinquency," on Salt of the Earth, the pieces on Hollywood and "The Sick Soul of Europe" never wear out. They're deep and funny and alive and most of all they make you say, what would it feel like to be that engaged with life, to care that much, to have so much fun doing something you clearly love?

Q. A critic friend and I have been having a conversation about whether being a failed artist -- or an aspiring artist -- is any value to a critic. I tend to dabble -- I write all sorts of things, I write songs and play music, while my friend contends he never wanted to play guitar or write fiction, he only wanted to be a critic.

On a practical level, I find it helpful that I can write about, say, James McMurtry's guitar gear with some confidence, that knowing something about how music is made informs my opinion. All this is a roundabout way of asking if you ever wanted to be Buddy Holly?

A. I always kind of thought I was Buddy Holly because Buddy Holly always looked like the kind of guy who got his locker slammed in his face in high school. But I have never wanted to play an instrument, write fiction or make movies. I always knew I could write and liked doing it, but it never occurred to me to "be a writer." I fell into it because I was bored to death in graduate school, was reading the then-new Rolling Stone and thought, reading their record reviews, I can do better than that, so I began sending pieces in and they printed them. When I decided, three years later, to drop out of graduate school, I didn't know how to do anything else.

I still have no desire to write a novel and I know I couldn't even play a Stu Sutcliffe back-to-the-audience bass. I don't know if criticism is an art, as Pauline always thought it was, but it takes all I have.

Q. Conspicuously absent from Mystery Train is Bob Dylan (he's not absent, but he's not the central subject of one of the book's essays). Did you consider focusing on him for a chapter? Or was he too large?

A. My idea was to focus on people who either had not been written about to any great extent or who had not been written about well. Dylan fell outside of that, so I never looked back. Of course, I've since written two ground-up books on Dylan and published a 42-year collection. But he would have upended the book, I can see in retrospect. It would have become a sort of Dylan vs. Elvis Battle of the Bands, as it is in "American Pie."

Q. Mystery Train was first valuable to me as history text, and later as a manifesto about the vitality of American popular music. Now it seems like an impossibly prescient document, though I honestly doubt whether Robert Johnson or even Randy Newman would hold their place in our culture had it not been for the book. How does it feel to you 40 years on?

A. I had tremendous fun updating and rethinking all the back sections of the book. I'm old enough now not to have any sense anymore of what "40 years" means or feels like. It doesn't feel that long ago that I wrote the book. I'm still the same person. I'm married to the same person. I was born in San Francisco and have never lived more than 30 miles away. It pains and shocks me sometimes that after I finished the book, the careers of everyone but Randy Newman came to an effective end (though Levon Helm made that startling return near the end). But they still remain fascinating stories and to follow them, even after the people whose stories they are are dead, is still thrilling.

The thing is, I always thought of the book as a kind of manifesto ... about criticism, saying there are no limits to what you can say about the art you love, and no limit as to what it can say to you. A kind of how-to book. The best compliment I ever got in a way came from Bob Dylan when I met him in 1997. He was being awarded the Gish Prize and I'd been invited to speak at the ceremony, along with Richard Avedon, who had known Dylan for years. We were introduced, and talked, then he asked what you ask a writer when you can't think of anything else to ask: "What are you working on now?" Invisible Republic [Marcus' book about the cultural importance of Dylan and the Band's The Basement Tapes] had just been published, although he had read it much earlier in the year, and I'd been told he liked it.

I said, "Oh, nothing, I just finished a book, I don't have a new project."

He said, "Why don't you write part two of Invisible Republic? You only scratched the surface."

That meant he'd really read the book -- I knew how right he was, and he knew the stuff I was writing about was bottomless.

When [Mystery Train] was first published, I knew what its weaknesses and evasions were, but I also knew it was better than anything else anyone had written on rock 'n' roll and that I'd written as well as I could, then. I thought, "I won't have to apologize for this." I've never rewritten the chapters of the book -- I have corrected errors. The chapters are essays, or plays; they have arcs, they have endings, they have gonging sounds at the end.

Q. What are you working on now?

A. I'm proofing Real Life Rock -- The Complete Top 10 Columns, 1986-2014, which is going to be a very long book. Soon I will be proofing Three Songs, Three Singers, Three Nations, drawn from the Massey Lectures in American Studies I gave at Harvard in 2013, on three songs that contain or create different countries, different Americas ... I continue writing the column at the Barnes & Noble Review. And that's all I'm doing, aside from preparing for two seminars I'll be teaching at the CUNY [City University of New York] Graduate Center in New York in the fall and a lecture course on the year 1948 as a transforming year in American life at Berkeley in the spring of next year.

Q. I carry this quote around with me: "I am no more capable of mulling over Elvis without thinking of Herman Melville than I am of reading [Puritan preacher] Jonathan Edwards without putting on Robert Johnson as background music."

I'd submit that Mystery Train is, among other things, about the pure products of America, the changelings who go crazy. It's tempting to say that the corporatization, professionalization and digitization of the music business has changed all that, but I think there may still be some space for the kind of primitive, feral artist. Who are the inheritors of the tradition and why?

A. Bob Dylan. By this time he is his own inheritor. He has become the kind of spectral folk figure -- like Dock Boggs or Son House or the Carter Family -- he once thought of as mysteries. His own songs have entered the language so that they are closer to "The Coo-Coo" or "Black Jack Davy" in terms of who they reach and how, than they are to, say, Beatles songs.

And countless other people, too.

Q. You talk a little in the Author's Note about how the book came to be, but it seems to me above all an ambitious work of synthesis. How do you account for the nerve of your 30-year-old self?

A. I wasn't 30 when I started writing. I was 27 and I was 28 when I finished and 29 when it came out. I didn't think about audiences or reception. All I thought about was getting through it. I'd never written a book before and it was all-consuming, a deadly threat. I wanted nothing so much as to be hit by lightning so I'd have a legitimate, honorable excuse not to finish it ... I hated everything about it and I hated myself. Until, after struggling through the Randy Newman chapter, I got to The Band -- the last part I wrote -- and it was like sailing down a river in a canoe. It was easy, it felt good, and all the songs were at my feet, and I had those last words from Dominique Robertson hanging in the air over my head, and all I had to do was get to a nice, quiet place where they would end the chapter, and for me end the book. I finished that chapter in the living room of my house at 3 a.m. and fell asleep.

My wife found me that morning and I told her I'd finished the book. She read the chapter and said, "Yes, you did."

It wasn't a question of nerve. I'd dropped out of graduate school in political theory at Berkeley ... because I'd been given the chance to teach the sophomore American Studies seminar, a class that completely changed who I was or drew out who I was, a self that had been invisible to me, when I took it in 1964-65. It was a great honor. Along with an English professor and a history professor, I chose the students, I chose the reading, I taught the seminars, I was responsible to no one. I was a terrible teacher and hated every class. I had no patience. I realized I was not cut out to be a teacher, and I'd had enough bad teachers not to want to become one. So I quit, wrote record reviews and [wrote] about everything else -- movies, politics, books, ideas, mostly for Creem -- and then was frustrated, the forms were too limiting, I had to do something more. How the book came to be what it is is a long story ... but, again, by a certain point all that mattered was getting out of it.

I wrote the Harmonica Frank chapter and the Epilogue in one afternoon without knowing why or how they might fit into the book. I spent forever on the Robert Johnson chapter. All in all it took two years, which seemed like the longest years of my life. I did nothing else. I wrote nothing else.

Q. The essential problem of rock 'n' roll has always been how to remain relevant. Of the figures you wrote about in Mystery Train, only Randy Newman seems to have found a way to remain vital (and he, never a prolific writer, seems to have slowed down considerably). Dylan carries on in his way as a Leadbelly-like songster and Leonard Cohen and Paul Simon both seemed to have escaped becoming nostalgia acts, but they're exceptions. Why do rock musicians seem to age so poorly?

A. Drugs and touring. And with performers no longer really able to make money from records, but only from touring, it will only get worse. And, I think, a lack of legitimacy, a lack of being able to believe that your work is important, that it matters, that it deserves to last whether or not it does.

Q. Can I get a witness?

A. That I can't answer. As Marvin Gaye suggested, it's easier said than done.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

Style on 05/17/2015