FAYETTEVILLE -- The number of Northwest Arkansas' homeless has leveled off after years of rapid increases, but some school districts have seen a sharp jump in students without permanent homes, this year's regional homeless count found.

Almost 2,460 people in Benton and Washington counties are on the streets or living with friends or family, Kevin Fitzpatrick, a sociology professor at the University of Arkansas, said in a report this month based on hundreds of interviews conducted in January. That comes to about 0.5 percent of the population, meaning 1 out of every 200 people in the two counties were homeless at the time of the survey.

Student homelessness

District20132015

Bentonville294398

Fayetteville192207

Siloam Springs96153

Rogers162133

Gentry12791

Springdale15680

Farmington3334

Prairie Grove1933

Pea Ridge3826

Elkins2116

West Fork2512

Greenland610

Gravette22

Lincoln40

Total11751195

Source: Community and Family Institute, University of Arkansas

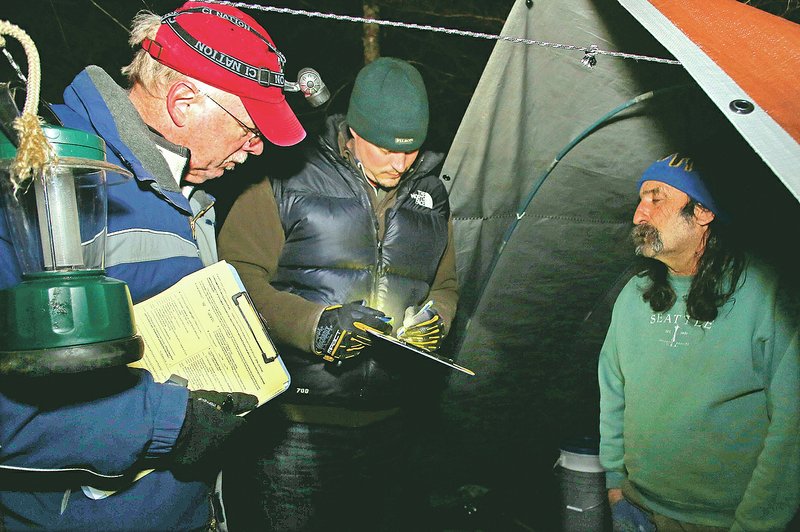

Fitzpatrick and a team of volunteers and social workers make the count every two years, and in 2013, they found around 2,430 people in such situations. The increase is small compared to its more than doubling since the first count in 2007, Fitzpatrick said, but homelessness still rose 10 times the rate of the overall population.

The work to address the problem isn't done, and it should focus on making and finding places for the homeless to stay, Fitzpatrick said.

"Affordable housing is a huge issue in this equation," he said. "Why are people living with their friends or their parents or their grandparents? Because they can't afford another place."

A wide variety of paths lead to homelessness, Fitzpatrick said, a common refrain among homeless researchers and homeless people themselves. Loss of support or of a major relationship, a significant medical or professional event and substance abuse all can leave someone without a roof.

About a quarter are chronically homeless, while half of those counted were homeless for the first time, Fitzpatrick said. About a third are working, Fitzpatrick said, while most have some kind of disability.

"There are common denominators, but there isn't generally a single, 'Hey, this is why I'm homeless,'" he said, saying many homeless people aren't obvious. "This story is not soup kitchens and skid rows and day centers where people hang out. It's part of our story, and it remains an important part. But the bigger story is who can't we see."

Visible and Invisible

Fitzpatrick's census differs from federal and other counts that include only people who are on the streets or in a shelter, a narrower description of homelessness that yields lower numbers than Fitzpatrick's.

The National Alliance to End Homelessness, for example, found about 3,000 people fit the narrower situation in the entire state of Arkansas in 2014, down 23 percent from the year before. This puts the state's homelessness rate at 0.1 percent, lower than most other states, the group's report found.

The narrow approach would count fewer than 400 of the homeless in Fitzpatrick's count, he said. It misses the region's more than 1,300 homeless children, including about 1,200 reported by school districts at the time of the count. Most are staying with friends and families. Children consistently have been half of Fitzpatrick's homeless population since 2009.

"When most people look at the number, it's the K-12 story that's probably the most baffling," Fitzpatrick said. "We're not getting a lot of traction there at all."

Like the overall number, the count of children hardly budged from 2013, but numbers in individual districts sometimes shifted dramatically.

Bentonville School District is home to almost 400 of them, up about 100 since the last count and once again the highest of any district. Siloam Springs' homeless students roughly doubled to more than 150. On the other hand, Springdale's count dropped by half to 80, according to the count.

Janet Schwanhausser, director of Bentonville Schools' federal programs, said it's not clear why Bentonville has such a high share. Bentonville's median income is about $62,000 a year, which comes in $4,000 higher than Lowell and $26,000 higher than Fayetteville, according to the U.S. Census.

"That's a good question -- I get that a lot," Schwanhausser said. "I think a small contributor to the issue is that we are really good at identifying which families qualify (for help)."

Bentonville has two social workers to work with students and their families, including one who was hired this school year, she said.

The district allows students to stay at their original schools and provides transportation even if a student has to move around the district to be with relatives. Lunch is free for homeless students, and the district's recently added Bright Futures program can help families with groceries and other needs while getting them in touch with community groups that can give more robust help toward finding a home.

Fayetteville and other districts run similar programs. Springdale and Siloam Springs spokespeople didn't return messages requesting comment this month.

"We are by far exceeding the assistance we were able to provide those families last year," Schwanhausser said, but with the population continuing to grow, she expects the homeless number to go only upward.

Area Plans

The region must devote more resources to this kind of help and take it further, Fitzpatrick said. He envisions a "continuum of care" from the streets to permanent housing: essentially, more help and more regional coordination.

At one end, people need more emergency shelters, dental and medical care and clean water, Fitzpatrick said. He pointed to the metro's two Salvation Army shelters, Fayetteville's Seven Hills Homeless Center and Washington Regional Medical Center's free mobile dental clinic, saying they're overwhelmed by the need.

At the other end, the area needs more transitional and permanent housing, including affordable one- and two-bedroom apartments, Fitzpatrick said.

Giving housing top priority is gaining traction around the country as local governments experiment with "housing first" programs, which provide apartments to the chronically homeless before getting them help with medical care or job training. Groups taking this approach have found it costs the same, if not less, as leaving people on the streets and picking up their tab for emergency room visits or jail time, while more effectively solving the problem, according to reports in Mother Jones magazine and other news outlets.

"You actually need housing to achieve sobriety and stability, not the other way around," Sam Tsemberis, a New York University psychologist who researches homelessness, told Mother Jones in the magazine's March/April issue this year.

During the January count in Northwest Arkansas, several people living in tents agreed housing was the key to climbing out of homelessness.

"There's twice as many campers as you think," Cybil Baker, 28, said as she ate a chicken lunch at Central United Methodist Church in Fayetteville. She had left her mother's home because of domestic abuse, and called for more shelters that didn't separate families.

"I think they should have more homeless shelters than just one," said Breanna Flynn, 17, referring to Seven Hills. Flynn was also living in a tent in a wooded area of town. Her plan was to try getting a job, then getting an apartment.

A roof over her head would help, Fitzpatrick said, but area groups must work together more to make it happen. He said the region has no overarching plan to end homelessness. Officials at the Northwest Arkansas Council and Northwest Arkansas Planning Commission said they weren't aware of any such plan, either.

In Fayetteville, Fitzpatrick, the Salvation Army, Seven Hills, the police and the mayor are discussing a village of "microshelters," a clean, safe shed for people, particularly homeless veterans, to stay. Where it would be and who would pay for and run the area are still complex, unanswered questions, Fitzpatrick said.

"Right now we're zeroing in on veterans, but it'll end up encompassing all of the homeless people to see what can be done," Mayor Lioneld Jordan said. The city and region don't have specific plans of action to end homelessness, he said, "but there is a group of people that's certainly working on it. I hope that someday we can completely eradicate homelessness."

Meanwhile, Fitzpatrick's homeless study for this year continues with more in-depth interviews of homeless people across the two counties to learn about their health, where they came from and hundreds of other variables to add more and more detail to the picture of Northwest Arkansas' homeless.

"This is my life's work," Fitzpatrick said. "We're in the field right now."

NW News on 05/18/2015