When he was coming out of high school, nobody saw Freddie Scott making a living as a football player. But the self-described “skinny country boy” from Pine Bluff forged an improbable path through a small Eastern liberal arts school to a nine-year career in the NFL.

“There were so many athletes better than me in high school,” Scott says.

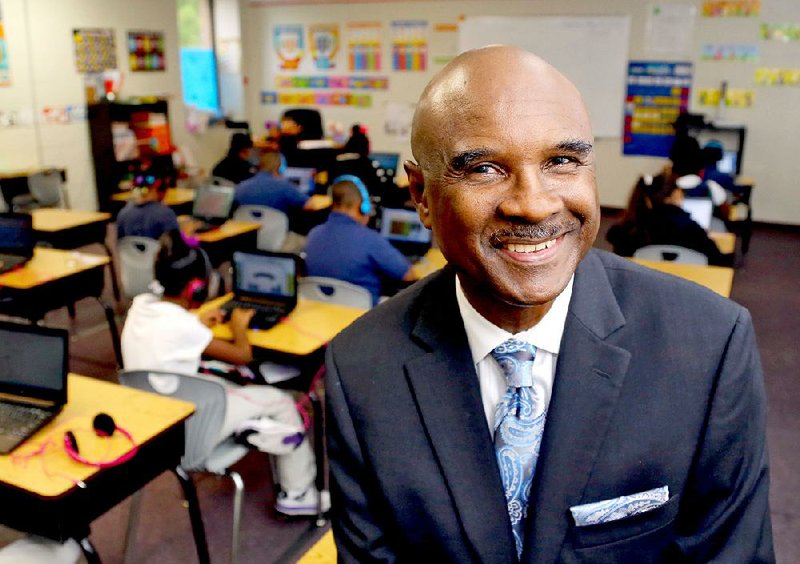

Some say the students at Exalt Academy, a charter school for poor kids in southwest Little Rock, don’t stand much of a chance either. Scott, an executive with the charter school’s parent company, believes otherwise.

And people who know him — even those with concerns about charter schools in general — say no one will work harder than Scott.

“I know he’s going to be dedicated to it,” said Marion Humphrey, a former Pulaski County circuit judge and friend since childhood. “I’m confident that he’s in it for all the right reasons. He’s always been a person who’s been concerned about others.”

Scott grew up poor himself. His father died before he was 2; his mother, Mary Lee Scott, moved Freddie and his younger sister, Diann, from Grady to a tiny house in Pine Bluff two years later. “Not one bedroom — one room,” Scott said of the house.

He excelled in school — “It came easy for me to study” — and threw himself into extracurricular activities. “You name the club — I was president. I played sports just because my friends were playing.”

In the eighth grade, he skipped a practice to walk a girl home — and got hit by a motorcycle. Somewhere along the way, he says, he “found the competitive nature to succeed” in sports at Pine Bluff’s Southeast High, attended by black students. He was all-city and all-county in basketball, a center fielder on the baseball team and a starter on the football team as a senior. But Scott told his coach that if any college football recruiters expressed interest in him, he wasn’t interested.

“I was too skinny and afraid to get hit,” said Scott, who stood 6 feet 2 and weighed 155 pounds at the time.

Inspired by a local physician, Scott wanted to be a doctor. And the valedictorian of his class of 126 seemed to have found a way to do it.

The chance came thanks to Humphrey, who told Scott about a program called A Better Chance that sent promising minority students to live at colleges during the summer. The teenager spent the summer before his senior year at Amherst College in Massachusetts, which is consistently ranked among the most selective liberal arts institutions in the country. He returned there after high school as a scholarship student, majoring in black studies and minoring in pre-medicine.

A friend convinced him to join the school’s football team. Amherst wasn’t what you’d call a traditional football power. The Division III team practiced three times a week and played a short schedule against similarly sized New England schools.

But Amherst had a coach, Jim Ostendarp, who produced four National Football League players during the 1970s. Scott caught more passes than any college receiver in the nation during his junior year and was named to the Associated Press Little All-America Team as a senior. He was drafted by the Baltimore Colts in the seventh round.

“People said I could not.”

The former pro football wideout and College Football Hall of Fame inductee who flirted with medical school is now helping kids into charter schools and the bright future he enjoyed with the help of others’ guidance.

Scott, who graduated cum laude from Amherst, applied to medical school. Then a conversation with an NFL player and Amherst alumnus convinced him to try out for the Colts and give professional football a run.

“Part of it was my drive,” he said. “People said I could not.”

GIVING FOOTBALL A CHANCE

Scott spent four years with the team in Baltimore. He’d added 15 pounds to his frame since high school — leaving him exceedingly light by players’ standards — which, along with his medical interests, earned him the nickname “Bones.”

He played as a backup for Baltimore, catching only 39 passes during his time there, although there were highlights, like his game-winning touchdown catch against the Washington Redskins in 1977. His first child, Freddie II, was born in 1974, on the same day he caught his first touchdown. In 1976, Scott and some teammates recorded their own pop song, predating the Chicago Bears’ famous “Super Bowl Shuffle” by a decade.

“We called it the ‘Shake and Bake,’” Scott recalled.

Theirs didn’t catch on, perhaps because they lost in the playoffs.

Traded to Detroit, Scott led all Lions receivers from 1979-81 by catching 168 passes, including 14 touchdowns. “I became a student of the game,” Scott said, explaining how he succeeded without size or startling speed.

For four off-seasons, Scott was also a medical student, taking classes at Johns Hopkins, the University of Michigan and University of Cincinnati medical schools. As his football career stretched on longer than expected, Scott gave up his ambition of becoming a doctor. After leaving Detroit, Scott played one more year in the short-lived United States Football League as a member of the Los Angeles Express, catching passes from future NFL Hall of Famer Steve Young.

The skinny wide receiver who never liked getting hit avoided serious injury, relatively speaking.

Scott pointed a long finger to various points of his body — a shoulder (twice separated), a knee (two minor surgeries), his hips (contusions), his arm (broken), and his noggin (concussion). “Just basic football stuff,” he said.

Scott spent three years after football in Miami, teaching science in public middle and high schools. He liked the work but realized his salary of $18,000 would not support his family, which by then included three children.

He returned to Michigan and took a job with IBM. In 1995 he graduated from the Word of Faith International Christian Center School of Ministry in Michigan. Eventually he started his own consulting business, F. Lee Scott & Associates, which offered companies help with technology, education, health and executive coaching.

BACK TO SCHOOL

Scott’s return to the field of education came through his children. Two attended charter schools — schools that receive public funds but operate independently from the school districts in which they are located. Michigan is a leader among states in the charter school movement.

Scott, who carries in his pocket the calling card of someone with a strong if erstwhile Detroit connection — a cell with a 313 area code — did some public relations work for the Michigan Association of Public School Academies, which represented charter schools, and then was invited to join the board of one. For several years, he and partners operated three charter schools.

Scott knows that public teachers unions and others oppose charter schools as a drain on resources for traditional public schools, but he says the flexibility afforded to charter schools makes them ideal for catering to the most at-risk students.

“Not all charter schools are the same,” he said. “I can speak to the ones I’m aligned with. The ones I’m aligned with serve a particular mission; they serve kids that grow up in poverty. Is there money that flows out of other schools? Absolutely. But there are adult issues and there are kids issues.”

“A charter school that’s focused on kids, they work.”

In 2001, Scott was notified that his career at Amherst had earned him a spot in the College Football Hall of Fame. On the same night he received that news, he got a call from his doctor telling him that he had prostate cancer. Scott underwent successful surgery a month after his induction into the hall (alongside the likes of John Elway and Marcus Allen). These days, Scott urges just about every man he encounters who has reached 50 to get regularly tested for the condition.

In 2009, he found himself the subject of a different kind of attention. His oldest son, who’d followed him into both the NFL and the ministry, published a book called The Dad I Wish I Had.

“If you’re on the outside looking in, you go, ‘Wow, he must have a terrible relationship with his son,’” Scott says. “But before it came out, we talked and he shared that God had spoken to him and wanted him to do this book. It wasn’t until I had green-lighted it that it went to print.”

Scott concedes he didn’t spend enough time with his children during his demanding NFL career.

“There’s about 3 percent of it that speaks out about our personal father-son relationship,” he said. “The rest of the book is about fathers needing to spend more time with their kids.”

Scott agrees totally with that concept and says he “should be writing a sequel [to his son’s book] because we do have such a close relationship.”

Another son, Brandon, played football for Bowling Green State University, and Scott’s youngest son, Myles, is currently a standout player for a high school in Atlanta. Scott has two daughters — Dana, who he said is “very successful in market analysis” in Arizona, and Jade, an honor student and track athlete who lives with Myles and their mother in Atlanta.

COMING HOME

Love — and social media

— brought Scott back to Arkansas. “Believe it or not, I got a Facebook message,” he said. It was from his now-wife, Faye, whom he’d met 20 years earlier while visiting his mother in a hospital. They met again in 2011 and were married later the same year. The couple teach a prayer class together at Liberty Hill Missionary Baptist Church, where Scott is an associate minister.

“Now I’m able to follow my passions with someone I’m blessed to have helped me on the way,” Scott said.

A mutual acquaintance led Scott to meeting Ben Lindquist, founder and CEO of Exalt Education. That in turn led to an invitation to join the nonprofit’s board, and then a job with Exalt as director of regional development.

“I was really impressed with the depth of his background in charter schools,” Lindquist said.

Incorporated in 2011, Exalt has three campuses in Little Rock, with 400 K-8 students attending Little Rock Preparatory Academy, and 111 K-2 pupils at Exalt Academy. One of Scott’s first jobs was helping relocate the Preparatory Academy’s elementary school from Liberty Hill Baptist Church to its current home at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral, on Spring Street, which gave it much needed space.

Scott Gordon, a retired hospital executive and Trinity member who worked with Scott on that move, noted that Scott makes time for numerous community activities, among them Promise Neighborhood, a coalition focused on central Little Rock, and Arkansas Natural Wonders, a council concerned with children’s health issues.

“He’s such a vibrant person. Whatever he gets involved in, he gets heavily involved in,” Gordon said.

Lindquist said Scott was crucial in all aspects of starting Exalt Academy, from putting together a board of trustees and getting approval from the State Board of Education to finding a campus and recruiting students from its surrounding neighborhood. The school is just off Geyer Springs Road.

“He was really kind of a one-man show in getting everything ready to go this year,” Lindquist said.

The school opened Aug. 18 and will complete its first year of classes June 25. Both its class day and school year are longer than that of public schools.

Scott said the school’s first week, it “was a typical school from hell. Now today they walk in line, they listen to their teachers, they’re learning.”

The plan is for the school to add one grade each year, up to the eighth grade, and Scott is already helping recruit students for next year’s classes.

Scott isn’t directly involved in Exalt’s academics, but he’s a big presence on its campuses. Principal Tina Long said the schools’ black male students especially look up to Scott as a role model. Trim and sharpdressed, he still moves like an athlete, on the balls of his feet. But when Scott talks about what’s happening at Exalt, it’s in the vein of a favorite biblical theme — planting and harvesting seeds — rather than rahrah locker-room bravado.

“We’re facing kids where people are saying, ‘Wow, they’re academically behind, they can’t get it, they will not succeed,’” he said. “What we’re doing is planting seeds that they will be on track for college, they will have a career.”

“It may not happen overnight, but we believe there will be harvest.”

SELF PORTRAIT

Freddie Scott

DATE AND PLACE OF BIRTH: Aug. 5, 1952, Grady

GROWING UP, MY HEROES WERE: Paul Warfield, Professor Asa Davis, Dr. Robert Smith

FAVORITE MOVIE: The Shawshank Redemption

I RELAX BY grilling on the deck, observing God’s nature, and listening to the still small voice of God in prayer. An occasional game of bocce ball is competitive but very relaxing as well.

THE TOUGHEST NFL PLAYER I FACED is Hall of Fame cornerback and safety Ronnie Lott.

LAST PLACE VISITED: Rochester, N.Y.

MY CHILDREN THINK I AM funny, since I believe that I can still outrace them all.

GUESTS AT MY FANTASY DINNER PARTY: Jesus Christ, Abraham, Dred Scott, my biological father Emmitt Holmes, my gorgeous wife, Faye.

ONE WORD TO DESCRIBE ME: Humble

Exalt Academy’s first week last fall, it “was a typical school from hell. Now today they walk in line, they listen to their teachers, they’re learning.”