COLUMBIA, Mo. -- The president of the University of Missouri System resigned Monday because of escalating protests over incidents of racial discrimination on the system's Columbia campus.

Chancellor R. Bowen Loftin, who oversees the university, will also step down, the system's board of curators announced Monday evening. Loftin plans to leave his position at the end of the year and move to a new role as director for research facility development.

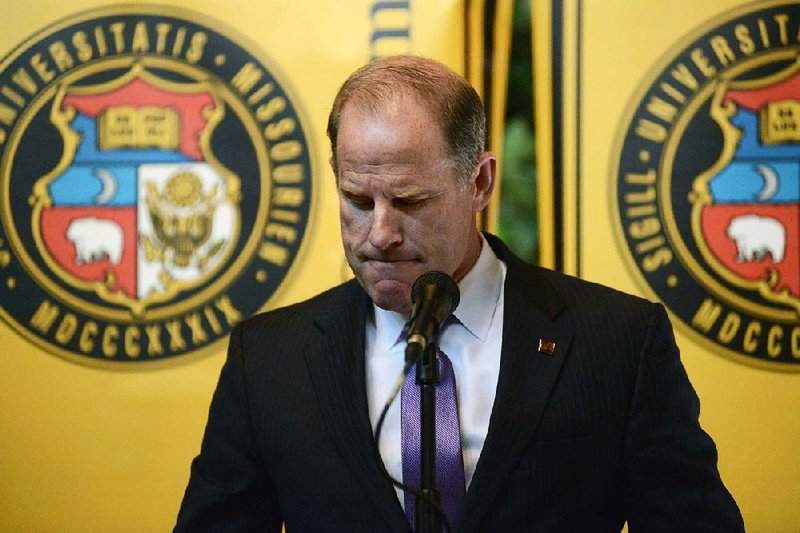

The university system's governing body announced Monday morning that President Tim Wolfe would step down immediately.

"My motivation in making this decision comes from love," Wolfe said. "I love MU; Columbia, where I grew up; the state of Missouri." But after thinking about the situation, he said, he concluded that resigning "is the right thing to do."

"This is not the way change comes about," he said, alluding to recent protests. "We stopped listening to each other."

He urged students, faculty and staff members to use the resignation "to heal and start talking again to make the changes necessary."

Seven percent of the University of Missouri's 35,000 students are black. Wolfe had taken little public action and made few statements in response to complaints of racial discrimination, and he soon became the protesters' main target.

Students had called for Wolfe's ouster, and the football team planned to boycott games until Wolfe stepped down. The athletic department announced Monday afternoon that the football team would resume normal activities today in preparation for Saturday's game against Brigham Young University.

Jonathan Butler, a graduate student who began a hunger strike to demand Wolfe's resignation, ended the protest after the president's announcement Monday. Butler appeared weak and unsteady as two people helped him meet with students gathered on campus to celebrate. Many broke into dance upon seeing him.

But some weren't pleased with the resignations. W. Dudley McCarter, a former president of the university's alumni group, said that alumni, in calls and emails Monday, had expressed disappointment in Wolfe's decision.

"They feel like he was backed into a corner and was made a scapegoat for things he didn't do," McCarter said.

The system announced that Hank Foley, the university's senior vice chancellor for research and graduate studies and the system's executive vice president for academic affairs, research and economic development, would become interim chancellor. An interim system president will be announced as soon as possible, according to a news release.

"It saddens me that some who have attended our university have ever felt fear, being unwelcome, or have experienced racism," said Donald Cupps, chairman of the board of curators.

"To those who have suffered, I apologize on behalf of the university for being slow to respond to experiences that are unacceptable and offensive in our campus communities and in our society," Cupps said. "Significant changes are required to move us forward. The board is committed to making those changes."

The board on Monday announced a series of initiatives, including plans to hire the system's first "chief diversity, inclusion and equity officer"; to review policies related to staff and student conduct; to provide additional support for students, faculty and staff members who have experienced discrimination; and to provide additional support for hiring and retaining a diverse faculty and staff.

How it all began

The debate over racial bias on campus began in September, when the undergraduate student body president said people in a passing pickup shouted racial slurs at him. Payton Head wrote about it on social media in a post that went viral.

A campus group, Concerned Student 1950, was formed. Its name refers to the year the first black student was admitted to the university. The group held multiple demonstrations this fall protesting what Butler described as a "slew of racist, sexist, homophobic" incidents -- and Wolfe's response to them.

A group of black students was rehearsing a skit in early October when a white student climbed onto the stage and shouted racial slurs. Protesters blocked the president's car during the homecoming parade a few days later; he did not get out and talk to them, and the demonstrators were removed by police.

In a recent incident, a swastika drawn in feces was found in a dormitory bathroom.

As the protests intensified, the group issued a list of eight demands, including Wolfe's removal as president. The group also demanded that Wolfe "acknowledge his white male privilege."

The university did take some steps to ease tensions. At Loftin's request, the school announced plans to offer diversity training to all new students, as well as faculty and staff, starting in January. On Friday, the chancellor issued an open letter decrying racial discrimination after the swastika was found.

In recent days, Wolfe had made increasing efforts to address protesters' concerns.

"Racism does exist at our university, and it is unacceptable," Wolfe said in a statement last week. "It is a long-standing, systemic problem which daily affects our family of students, faculty and staff. I am sorry this is the case."

On Sunday, in a new statement, he said: "It is clear to all of us that change is needed, and we appreciate the thoughtfulness and passion which have gone into the sharing of concerns. My administration has been meeting around the clock and has been doing a tremendous amount of reflection on how to address these complex matters."

But on Monday morning, the Missouri Students Association, which represents the school's undergraduates, formally called for Wolfe's removal. In a letter, it decried the administration's silence after the 2014 shooting of Michael Brown, a black man, by a police officer in Ferguson, Mo., and said Wolfe had "enabled a system of racism" on the Columbia campus and had failed the students.

"The frustration, the anger I see, is clear, it's real, I don't doubt it for a second," Wolfe said in announcing his resignation. "The faculty and staff have expressed their anger and their frustration. It's real.

"My friends and my supporters that have been so gracious, and sent so many emails and texts and calls for support, I understand that you might be frustrated as well."

He said the disputes were not the way change should come about, adding that "change comes from listening, learning, caring and conversation. We have to respect each other." He said that people need to stop yelling at each other and start listening.

But, he said, "I take full responsibility for this frustration" and for the university's inaction.

Wolfe, 57, is a former software executive and Missouri business school graduate whose father taught at the university. He was hired as president in 2011.

Loftin was hired as the University of Missouri's chancellor in 2013 after serving as president of Texas A&M University. Before the board announced his plans to step down, nine university deans released a letter Monday calling for him to be dismissed.

Missouri School of Journalism Dean David Kurpius said the deans had met with Loftin on Oct. 9 and then with Wolfe, Loftin and Provost Garnett Stokes to express concerns about the handling of "race and cultural" issues on campus.

The deans were also critical about other issues, including how the university tried to scale back tuition waivers for graduate assistants and strip them of their health insurance subsidies. After public outcry, the university reinstated the subsidies and agreed to leave the tuition waivers in place for a year.

"The environment on campus is not conducive to moving forward, resolving issues and trying to make sure that all of our students are in a good learning environment," Kurpius said.

Kurpius said that a final draft of the letter was finished Monday morning.

Only the first step

Within minutes of Wolfe's resignation, thousands of students assembled at the Carnahan Quadrangle, linking arms around the tents that have sprung up in recent days as a part of the protests. Students and teachers on campus hugged and chanted -- and talked about their continuing efforts.

"NEVER underestimate the power of students. Our voices WILL be heard," Head wrote after Wolfe spoke.

Butler told a cheering crowd that the graduate students' protests and the push against discrimination were part of a larger cause, citing months of protests, email campaigns and other actions calling for change on campus.

"It should not have taken this much, and it is disgusting and vile that we find ourselves in the place that we do," he said.

Sophomore Katelyn Brown said she wasn't aware of chronic discrimination at the school, but she applauded the efforts of black student groups.

"I personally don't see it a lot, but I'm a middle-class white girl," she said. "I stand with the people experiencing this." She credited social media with propelling the protests, saying it offered "a platform to unite."

"Tim Wolfe's resignation was a necessary step toward healing and reconciliation on the University of Missouri campus, and I appreciate his decision to do so," Democratic Gov. Jay Nixon said in a statement. "There is more work to do, and now the University of Missouri must move forward -- united by a commitment to excellence, and respect and tolerance for all."

White House spokesman Josh Earnest praised the protesters, saying they showed that "a few people standing up and speaking out can have a profound impact on the places where we live and work." It will require continued "hard work" on the part of students and administrators to ensure progress continues, he said.

Information for this article was contributed by Susan Svrluga, Kent Babb, Wesley Lowery and Rick Maese of The Washington Post; by Summer Ballentine, Jim Suhr, Alan Scher Zagier, Ralph D. Russo, Errin Haines Whack and staff members of The Associated Press; by Stephen Deere, Koran Addo and staff members of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch; and by John Eligon, Richard Perez-Pena and staff members of The New York Times.

A Section on 11/10/2015