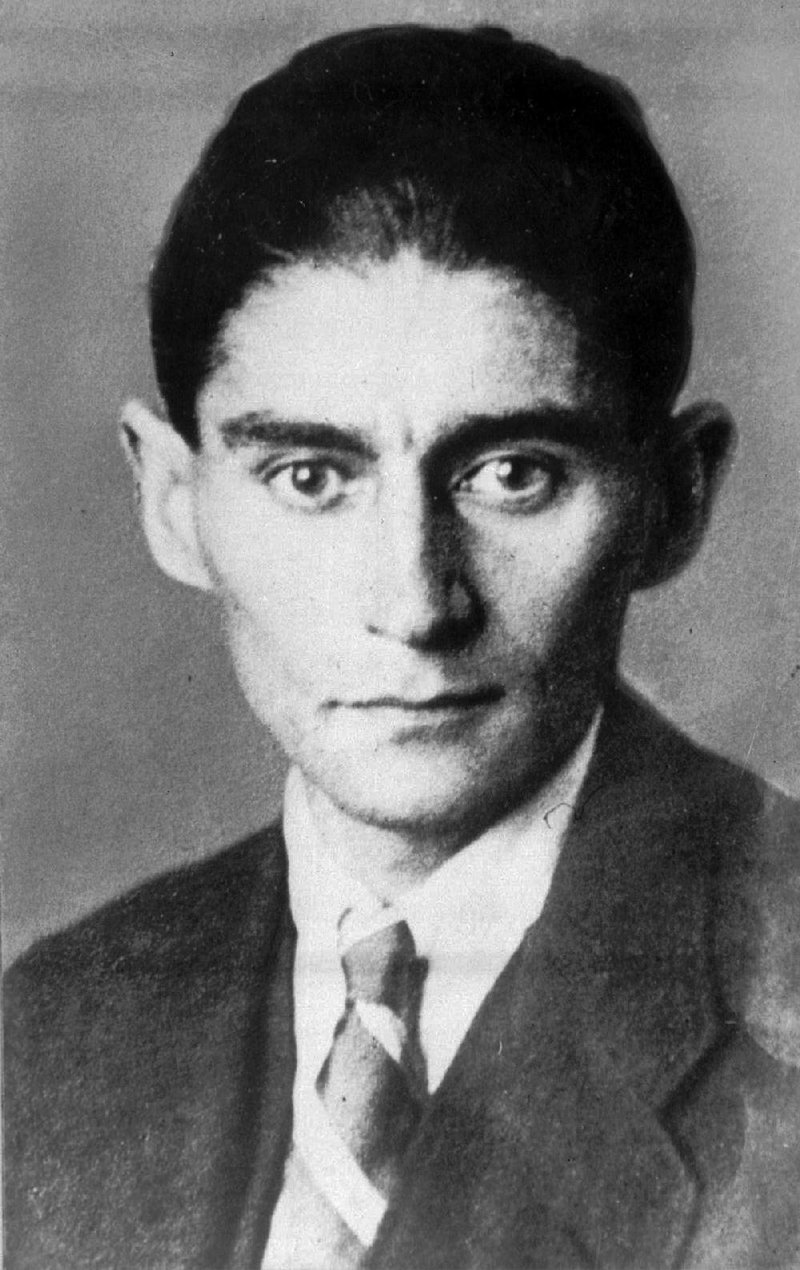

In 1973 Philip Roth published a weird and wonderful piece about Franz Kafka, a sort of essay-short story hybrid with the unwieldy title "'I Always Wanted You to Admire My Fasting'; or, Looking at Kafka." (The quotation is from Kafka's short story "The Hunger Artist.")

In this piece Roth starts out describing a photograph of Kafka taken in 1924, "as sweet and hopeful a year as he may ever have known as a man, and the year of his death." The piece goes on to imagine that Kafka did not succumb to tuberculosis but instead emigrated to America, avoiding the war and the Holocaust and becoming a Hebrew teacher in New Jersey, where one of his young pupils was named Philip Roth.

This fictional Kafka lived out his life in respectable poverty and never published the novels by which we know him. This seems a reasonable assumption given the real Kafka published little of note during his lifetime and destroyed most, maybe 90 percent, of his work. He directed his friend and literary executor Max Brod to burn his remaining manuscripts upon his death. Brod famously ignored Kafka's instructions; The Trial was published in 1925, followed by The Castle in 1926 and Amerika in 1927.

Kafka was a posthumous sensation.

Had Kafka lived to be an old man, an immigrant with a suitcase full of papers, he likely would not have become the literary equivalent of James Dean. Roth imagines him as a 59-year-old with sour breath and "a remote and melancholy foreignness." His students saddle him with a cruel nickname and mock "his precise and finicky professorial manner, his German accent, his cough, his gloom."

Indirectly, Roth argues that Kafka's early death was a form of redemption, saving him from the indignity of ordinariness. Brod's actions transformed the mortal Kafka into an icon. But what if he hadn't died?

If you're familiar with Roth's works, you might detect the echoes of this piece in his 1979 novel The Ghost Writer, in which the author's fictional alter ego Nathan Zuckerman finds a woman he imagines to be Anne Frank alive and living incognito in Connecticut. His 2004 book The Plot Against America is an alternate history speculating on the consequences of Charles Lindbergh defeating Franklin Roosevelt in the presidential election of 1940.

Because Roth often employs characters who share with him certain biographical facts (or are even called "Philip Roth"), some people assume that Roth is a writer who extensively mines his own life for his fiction. But there's more support for the idea that his work is speculative and conjectural. He's not writing what he knows -- he's writing what he is able to imagine.

I had thought I'd hit on something novel with this thought. But Google turns up a 1986 piece written for The New York Times by Mervyn Rothstein called "Philip Roth and the World of 'What If?''' It's collected in the George J. Searles-edited book Conversations With Philip Roth (University of Mississippi Press, 1992). In that article, Roth himself leans forth and lays it out:

"The actor wears the mask for public performance, the writer dons the mask alone in a room. He dons the mask of Humbert Humbert, the mask of Rabbit Angstrom, the mask of Stingo or Herzog or Holden Caulfield. Unmasked, he lives like everybody, primarily with 'what is.' As a masquerader he is generally more curious about 'what might have been' and 'what could be.'"

Years ago, Roth said in an interview that he came to Kafka relatively late, that he was already a published writer when he developed his fascination with the Czech. He read the novels and short stories, and taught them in his classes at the University of Pennsylvania in the early 1970s before he ever made his way to Prague, looking to commune with Kafka's ghost.

What if he hadn't? What if Roth hadn't made several trips to Prague in the 1970s?

A CZECH IN PARIS

Perhaps we can assume he wouldn't have become intrigued by the work of writers who lived and worked and sometimes died under totalitarian regimes. He would not have befriended the Czech Milan Kundera or conspired with Penguin USA to publish a paperback series called "Writers From the Other Europe" that introduced Kundera (The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, The Joke, Laughable Loves, The Farewell Party), Polish writers Bruno Schulz (Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass, The Street of Crocodiles) and Tadeusz Borowski (This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen), Yugoslav author Danilo Kis (A Tomb for Boris Davidovich) and others to the West.

We probably would not have Juliette Binoche cavorting in a derby in the movie version of The Unbearable Lightness of Being, based on Kundera's zeitgeist-capturing 1984 novel that examined the lives of free-spirited Czech intellectuals and artists living under the shadow of Sovietism. We might not have had the Velvet Revolution, which was informed by the novel's grim wryness and its recognition of the primacy of the sexy and the personal over the prim and political. I doubt we'd be paying any attention at all to the 86-year-old Kundera's most recent book, his first novel in 13 years, The Festival of Insignificance (Harper/HarperCollins, $23.99).

Insignificance is as slight as its title suggests. It's 115 pages of circular intellectual joshing and rude humor, the sort of thing that only a venerated wise man could get away with. It overtly teases the reader who suspects that perhaps it's a waste of time. It's a faint echo of Unbearable Lightness in that it also primarily concerns itself with the dynamics of five friends, but this time they're all male (in Unbearable Lightness there were two couples and a dog), and it's set in a libertine present-day Paris, largely in the Luxembourg Gardens where, in a surreal scene near the end, Stalin appears as a charismatic gadfly. The ahistoric French don't recognize him, but cheer when he shoots off the nose of a statue of Marie de Medici.

It's a goofy, quick read, and while there will be those who cringe at Kundera's portrayal of women, we probably shouldn't expect evolution at this late date. And it feels curiously empty. Without the great gray wall of Communism to echo off of, Kundera's jokes don't resonate.

THE AMERICAN

It's hard to say how highly Anthony Marra regards Kundera. But in a 2013 interview with the Stanford Arts Review, he acknowledged his fondness for Bohumil Hrabal, another Czech writer introduced to the West by Roth's "Writers From the Other Europe" series, which published his 1965 novel Closely Watched Trains in translation in 1981.

"In the Czech Republic everyone thinks Milan Kundera overrated, partially because he totally shunned the Czech Republic after he emigrated," Marra said. "As soon as he was able to, he only started writing in French and has refused to allow his books to be translated.

"But yeah, Bohumil Hrabal is their national literary hero. He was famous for having written the longest sentence, which took up an entire book. He has this etherealness to his writing; he goes off on these flights of fancy that are always underpinned by some historical tragedy in Europe."

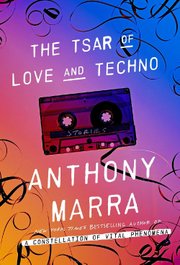

Even so, Marra's remarkable new book, The Tsar of Love and Techno (Hogarth, $25), put me in mind of Kundera's 1980 novel, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, which describes how Vladimir Clementis, a real-life Czech politician and literary critic, was airbrushed out of a 1948 photograph in which he was standing next to Klement Gottwald. (After a coup d'etat, Gottwald became president of Czechoslovakia. Clementis was executed.)

Marra's book begins in 1937 in the tunnels beneath Leningrad, with a man named Roman Osipovich Markin, who considers himself "an artist first, a censor second." A former painter who puts his talents to use correcting history by airbrushing unfortunate persons out of photographs, he also smooths Stalin's pocked cheeks, a grace that wins him a bit of favor with the despot.

Then he's ordered to remove his own brother Vaska, a man executed for "religious radicalism," from a photograph. Roman does so, but a switch goes off in his heart and he subversively begins to paint Vaska's face into crowd scenes. He paints him as an adult, as a child, as the old man he would never become. Vaska begins to appear -- like Woody Allen's Leonard Zelig -- everywhere, a ghost haunting the official record.

Inevitably, Roman, too, is arrested. It hardly matters why, although it has something to do with a disgraced prima ballerina whom he incompletely obliterates from history. We get her story later, along with that of the Chechen brothers Alexei and Kolya, and the fading movie star Galina, as the novel skips from the 1930s to the present day to beyond, from Leningrad to Kirovsk in Siberia to Chechnya to the edge of the solar system.

Technically, this minor miracle is a series of short stories, but they are so tightly interwoven that you'd be best served by approaching it as a novel. Read it sequentially, and wait for the details to lock in place. Minor characters become important; hardly a word is wasted. It's an exquisite machine.

But it's more than that. Marra is a writer of uncommon power and precision, and this is an ambitious book that's even better than his debut novel, 2013's A Constellation of Vital Phenomena, which also concerns itself with Russia and the Chechen war and made all the year-end "Best Of" lists. It's about the bonds of family and the way history impinges upon the future. It's about how an individual spirit can persist and prevail over bureaucratic terrorism. It's a book about love and empathy, glazed with gloom and bitter black humor, and it's set in wonderfully realized Other Europe.

Realized, by the way, by an American writer who grew up in Washington and attended the Iowa Writers' Workshop and Stanford. He spent his junior year of college in St. Petersburg but didn't travel to Chechnya until he was almost finished writing Constellation.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

Style on 11/15/2015