Birdwatchers and researchers have grown used to looking up species records on the Internet, but the Internet doesn't have access to all the records that Arkansas birders have kept. Yet.

Three decades' worth of Arkansas Audubon Society documentation of species seen here, and when and in what numbers and by whom, pre-dates the digital era -- which for these intents and purposes began in 1986 with the creation of the electronic Arkansas Bird Records Database.

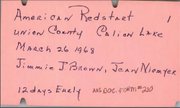

From the 1950s to the '80s, the state's most systematic database of bird science was recorded on 3-by-5-inch index cards -- tens of thousands of them. And there, for the most part, it remains.

The cards provided the information in the book Arkansas Birds: Their Distribution and Abundance (University of Arkansas Press, 1986), still the most definitive guide to Arkansas species. "But that's a book. It's not accessible to the wider audience, to everyone out there," says Dan Scheiman, bird conservation director for Audubon Arkansas.

Scheiman is volunteering with the Card-inal Club, an effort to transcribe every last one of the index cards into a digital database. And that's about 34,000 cards.

Volunteers -- who numbered 40 last week -- are working on their own schedules, on their own computers, "all on their own," he says. "I send them the instructions, spreadsheet and batches of cards that have been scanned into PDF files by species. They type the information they see on the cards into their Excel spreadsheet and then send it back to me.

"And then I send the next batch of cards. They keep going."

The PDF images were created by Arkansas Audubon Society volunteers Carolyn Minson and Ann Gordon, who got them from the office of Douglas A. James, the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville professor of zoology who originated rigorous record-keeping of bird observations

in the state and, with co-author Joseph C. Neal, wrote Arkansas Birds.

(Neal told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette he vividly remembers going through the cards three times in assessing which records to put in the book.)

James began keeping his field notes on card files in fall 1953 as a new teacher of ornithology at the University of Arkansas. When the Arkansas Audubon Society formed in 1955, he became its first records curator, serving as the arbiter of bird-sighting data from 1955 to 1973.

"Because there really wasn't any compilation of bird records, and we didn't have any information as to the seasonality, the occurrence across the state, nesting records for all these species, Doug James asked people to submit everything they were seeing," Scheiman says.

So these 34,000 card files are not confined to notes about rare birds.

"We think today, 'Oh, I see the cinnamon teal on the Arkadelphia oxidation ponds' and you submit that to the Bird Records Database, which is mostly rare birds or first state records, first county records, that kind of stuff. But this [trove] includes all those rare birds and also sightings from across the state of all the common species.

"It's all times of the year, all throughout the year, every year" -- up to the introduction of the electronic Bird Records Database. (It's online at the Arkansas Audubon Society website, arbirds.org.)

Some cards were handwritten, but most were typed. And they are color coded, with different colors representing different regions of the state.

James took pains to include records from birders collected before 1953. Thus the cards include data from people like Ben B. Coffey Jr., who observed birds statewide but mostly in the eastern and northern counties beginning in 1929, and M. Brooke Meanley, who stalked the lowlands of eastern Arkansas from 1951-1962.

The contents of the cards are already known -- James and Neal put it into Arkansas Birds -- and so the transcription project isn't uncovering unexpected rarities. But digitization will benefit researchers, Scheiman says. "The further back in time you go for eBird, the fewer records there are," he says. "So it's really important to get those historical data sets into eBird, to fill in the gaps."

More volunteers are welcome to join the effort, Scheiman says. They can contact him via email at birddan@comcast.net.

ActiveStyle on 11/30/2015