COLUMBIA, S.C. -- A canal in South Carolina's capital city that serves as the main source of drinking water for about half of the water system's 375,000 customers collapsed in two places after record rainfall and flooding over the weekend.

Contractors in Columbia have been scrambling to build a rock dam to plug the holes while National Guard helicopters have been dropping giant sandbags in the rushing water.

Water from the canal normally flows directly into the reservoir at the city's water-treatment plant. But with the water level falling because of the levee breach, workers were forced to place orange pumps on the banks of the canal to pump water directly into the reservoir. And if that wasn't enough, the city had plans to pump water directly from the nearby Broad River.

Officials sought to beat back rampant rumors of an imminent water shortage.

"The system is running and it is running strong," Columbia Mayor Steve Benjamin told reporters.

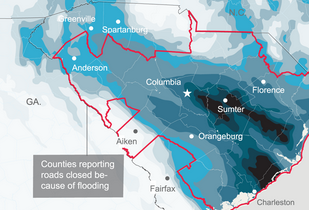

Meanwhile, Gov. Nikki Haley issued a terse warning to thousands of people in low-lying areas near the coast to "strongly consider evacuating" before a mass of water rumbling toward the ocean floods some places for up to two more weeks. Any mandatory evacuations would be ordered by local officials.

She asked people watching on television to call relatives who may have a false sense of security after surviving hurricanes, calling the second round of expected flooding "a different kind of bad."

She said the standing water could last up to 12 days.

"We have thousands of people that won't move. And we need to get them to move," she said. "They don't need to be sitting in flooded areas for 12 days."

Back in Columbia, city officials urged residents to conserve water. And when they do use it, they have to boil it at least one minute. Restaurants are offering bottled water and serving meals on paper plates to avoid washing dishes. And many people often make daily trips to grocery stores to stock up on water.

"It's easy to conserve because you can't really use [the water]," said Laura Reinman, 26, who was pushing a shopping cart with two gallon jugs of water at a Publix grocery store just across the street from the canal.

The city is like hundreds of others along the East Coast and in the Midwest that have been told to fix their aging infrastructure.

Columbia is under orders from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to fix its sewage-treatment plant and sewer pipes to reduce overflows that can contaminate waterways. Those orders include spending $1 million on projects to reduce flooding along Gills Creek, one of the areas devastated by record rainfall and flooding.

And last month, the state Supreme Court revived a lawsuit challenging how the city has paid for maintenance to its water and sewer systems, saying "simply put, the statutes do not allow these revenues to be treated as a slush fund."

Columbia separates its property tax collections, which are only imposed on city residents, from its water fees, which are paid by its customers who live throughout the region. In 1993, the city passed a resolution allowing it to pull money from the water fund to help balance the city's budget. According to the lawsuit, in the past three years, $12 million has been transferred from utility customers to pay for nonutility projects, such as economic development and efforts to lure businesses to the city.

Benjamin said the city has reduced the transfer over the past several years. This year, it was $2.8 million to help pay for police, fire and 911 services.

Information for this article was contributed by John Seewer and Meg Kinnard of The Associated Press.

A Section on 10/09/2015