WASHINGTON -- President Barack Obama said he's eager to sign the two-year budget deal passed by the Senate in the pre-dawn hours Friday in hopes of breaking a "cycle of shutdowns and manufactured crises" that have hurt the U.S. economy.

Senators voted 64-35 for the measure, which will spare the nation a default on its loans and a partial government shutdown. Democrats teamed with Republican defense boosters to overcome opposition from conservatives who included three GOP senators running for president -- Marco Rubio of Florida, Rand Paul of Kentucky and Ted Cruz of Texas. They were joined in opposition by Arkansas' senators, John Boozman and Tom Cotton, both Republicans.

Obama had negotiated the accord, passed by the House earlier this week, with congressional leaders who were intent on avoiding the brinkmanship and shutdown threats that have haunted the institution for the past several years. Departing Rep. John Boehner of Ohio made it his top priority in his final days as speaker before making way for Rep. Paul Ryan, R-Wis., who took over the leadership Thursday.

The White House said Obama would sign the bill Monday.

In a statement issued early Friday, Obama said the deal shows Congress can "help, not hinder" the nation's progress. He urged lawmakers to work on other needed spending measures "without getting sidetracked by ideological provisions that have no place in America's budget process."

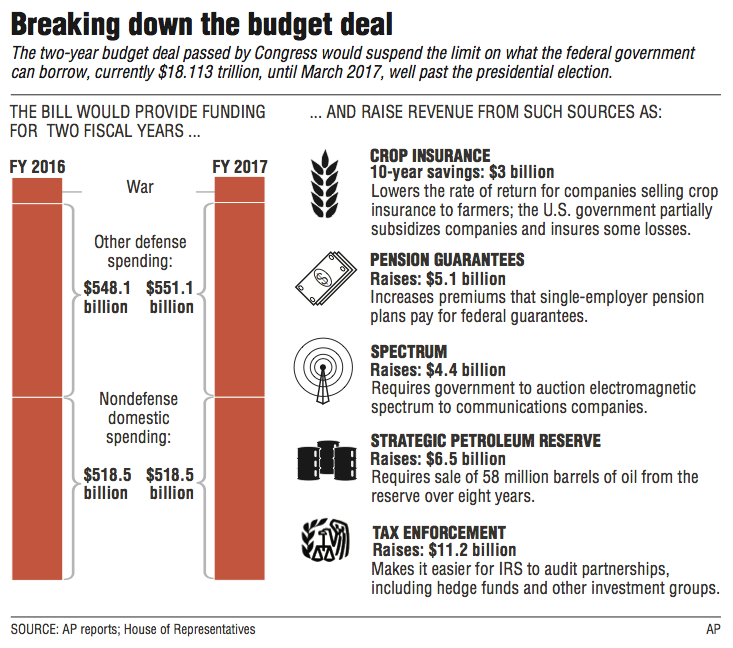

The government's already hit its current $18.113 trillion borrowing limit. Setting a new ceiling by specifying a future expiration date gives lawmakers a clear deadline for renewing it again.

The new budget agreement allows federal borrowing until March 15, 2017, without specifying the amount of money. Lawmakers have changed the debt ceiling 15 times since 2001, when the ceiling was $5.7 trillion, including debt-limit suspensions in 2013 and 2014.

The deal sent to the White House allows members of both parties to look ahead toward next year's presidential and congressional elections. Republican leaders were particularly concerned that failure to resolve this vexing matter could reflect poorly on their ability to govern. There was significant opposition in the Senate, nevertheless, as Paul and Cruz made it a point to be on the floor to register their concerns.

In an hour-long speech that delayed the final vote to about 3 a.m. in Washington, Paul said Congress is "bad with money." He railed against increases in defense dollars supported by Republicans and domestic programs supported by Democrats.

"These are the two parties getting together in an unholy alliance and spending us into oblivion," he said.

Rubio said in a statement that the agreement delays "tough decisions until after the next election."

Cruz said the Republican majorities in both the House and Senate had given Obama a "diamond-encrusted, glow-in-the-dark Amex card" for government spending.

"It's a pretty nifty card," he said. "You don't have to pay for it; you get to spend it, and it's somebody else's problem."

Boozman in a statement issued after the vote called the budget agreement a "setback."

"We've made real progress toward restoring regular order to the budgeting process by passing all 12 appropriations bills out of the committee this year in the Senate. Those 12 bills are what we should be considering, not this last-minute agreement," he said. "The deal once again busts the budget caps in place by allowing for billions of additional spending over the next two years, all of which will be added to our already massive national debt."

Cotton said he couldn't support the budget agreement because it did "so little to cut spending or address the drivers of our debt."

"Arkansans are tired of the 'spend now, fix later' mentality that's become so common in Washington," he said in a statement.

While Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., and Harry Reid of Nevada, the chamber's top Democrat, described the budget deal as imperfect, each touted specific elements sought by his party. McConnell said it would enact "the most significant reform to Social Security since 1983," while Reid said it protects Social Security disability benefits from "deep cuts."

"Today's vote is a victory for bipartisanship and for the American people," Reid said in a statement after the vote. "Together, Democrats and Republicans have proven that, when partisan agendas are set aside, we can find common ground for the common good."

"The budget agreement is good for the middle class, good for the economy and good for the country," he said.

Medicare Funding

The agreement raises the government debt ceiling, removing the threat of an unprecedented national default just days from now. At the same time, it would set the budget of the government through the 2016 and 2017 fiscal years and ease punishing spending caps by providing $80 billion more for military and domestic programs, paid for with spending cuts and future savings and revenue.

The budget relief would lift caps on the appropriated spending passed by Congress each year by $50 billion in 2016 and $30 billion in 2017, evenly divided between defense and domestic programs. Another $16 billion or so would come each year in the form of inflated war spending, evenly split between the Defense and State departments.

The promise of more money for the military ensured support from Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., chairman of the Armed Services Committee. Additional funds for domestic programs, such as Social Security and Medicare, pleased Democrats.

The deal works to avert a shortfall in the Social Security disability trust fund that threatened to cut benefits, and to head off an unprecedented increase in Medicare premiums for outpatient care for about 15 million beneficiaries.

Democrats had sought a simple transfer of payroll-tax revenue from the Social Security retirement fund to the disability account. Republicans got changes to the program but agreed to allow the adjustment, temporarily increasing the contribution from 1.8 percent to 2.37 percent of wages.

The deal prevents a major increase in Medicare premiums next year for some recipients by applying a surcharge in later years. It also increases rebates paid by drug manufacturers to federal and state governments to cover the cost of Medicaid and change the way Medicare pays for services at hospital-owned doctors' offices.

The budget deal is paid for, in part, by the U.S. selling 58 million barrels from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, which raises about $6.5 billion. It also changes the way partnerships such as hedge funds and private-equity firms are audited to increase tax compliance, raising $11.2 billion, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

The proposal uses war funds, which aren't subject to budget caps, to increase defense spending, something Obama has previously opposed. It would raise the Defense Department's overseas contingency operations and the State Department's war funds by more than $7 billion apiece each year over the Obama budget request.

The White House had projected a larger decrease in war funds because of the ending of the conflict in Afghanistan in 2017, but the budget deal maintains spending higher levels through that year.

Overall, the measure gives Obama almost 90 percent of the additional money for domestic programs he asked for in February and lifts spending limits that the administration contended were hindering the economy.

The agreement diminishes, but doesn't eliminate, the odds of a government shutdown because lawmakers still must work out details before current funds expire Dec. 11.

Lawmakers had been racing against a Tuesday deadline to avoid a debt default. The plan faced opposition from some Senate Republicans, who said many of the cuts were gimmicks and that the package overall would add to the nation's debt.

Critics of the deal also said it would breach spending-cap agreements they considered a much-needed step toward responsible cost controls. Democrats have long called for lifting the caps, which they say have put a drag on the economy and blocked needed investments in infrastructure and other programs.

"Ultimately, there was something passed called sequestration, which put caps on both military and domestic spending, and it did slow down the rate of growth of government for a little while," Paul said in his floor speech. "This is the problem with Congress. Congress will occasionally do something in the right direction and then they take one step forward and two steps back."

Sen. James Lankford, R-Okla., said people in his state did not buy arguments in favor of the budget accord.

"It was announced by the White House today that this is a great job-creating achievement," he said, "but all they see is more spending and no change in the status quo."

Obama had repeatedly said he would not negotiate budget concessions in exchange for increasing the debt limit, though he did agree to package the debt and budget provisions.

"I am as frustrated by the refusal of this administration to even engage on this [debt limit] issue," said Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch, R-Utah. "However, the president's refusal to be reasonable and do his job when it comes to our debt is no excuse for Congress failing to do its job and prevent a default."

Information for this article was contributed by Andrew Taylor, Mary Clare Jalonick and Alan Fram of The Associated Press; by Terrence Dopp and Kathleen Miller of Bloomberg News; and by David M. Herszenhorn of The New York Times.

A Section on 10/31/2015