DAMASCUS -- A crowd gathered in this flower-speckled cow pasture two Saturdays ago to learn what happened here Sept. 19, 1980, when rocket fuel exploded, blowing a 9-megaton Titan II missile warhead out of its silo.

Air Force Senior Airman David Livingston, 22, died in the blast. Twenty-one others were injured. The warhead did not detonate. (Obviously.) But a lot of people were justifiably afraid, because a 9-megaton warhead is a serious thing.

Thirty-five years later, about 100 people stood in the sun for two hours on a "Walks Through History" tour conducted by the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. The agency's Rachel Silva gave a presentation. So did Ken Grunewald, 70, a retired Air Force missile officer who was a missile commander in the 308th Strategic Missile Wing, when it was a tenant unit at Little Rock Air Force Base. He worked inside the silo here.

On the day of the explosion, Grunewald was no longer based at Little Rock and was not at Damascus. He was in the command center of the Strategic Air Command at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska, where the nation's foremost missile defense experts had no checklist for dealing with the unprecedented event unfolding in Arkansas.

"It was not a pretty sight," he said.

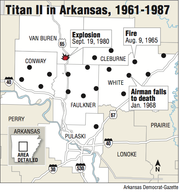

This cow pasture is a little more than three miles north of Damascus on U.S. 65. The missile planted here -- designated 374-7 -- was one of 18 scattered around the state and 54 around the country. The others were in Kansas and Arizona.

The area is still mostly farmland and pasture, but development is marching north from Greenbrier. Just south of the missile site, where U.S. 65 intersects with Arkansas 124, there's a relatively new traffic light.

Many more people live around here now than in the 1960s when the Air Force was looking for remote places, away from population centers and away from the coasts where the submarines of the Soviet Union lurked. Those subs might have been able to knock out missiles sited close by, but deep inside the American interior, a Titan II would have time to launch.

Russ and Lee Ann Matson of Little Rock were among those Sept. 12 who drove down a faint trail -- take a right at the cattle -- and parked near two mounds. The smaller mound is where the command center was located. The big mound was once the silo.

What does Lee Ann Matson recall about the disaster?

"I remember the tragedy and the worry it would keep happening," she said. "It was more of a worry than a fear."

Fear would have been understandable. It was 1980, a time of war, the so-called Cold War, described by Silva as a "prolonged state of political and military tension between the United States and the Soviet Union."

Cold, yes, in the sense the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics never engaged in direct conflict. Hot, though, by extension in Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan and elsewhere around the world.

Both sides built up their nuclear forces in response to the other, including

intercontinental ballistic missiles. It was MAD -- Mutually Assured Destruction.

Titan II missiles were the culmination of a furious arms race. Atlas missiles were the Air Force's first generation of ICBMs in the 1950s. Almost simultaneously, development began on the Titan I.

Both earlier missiles had disadvantages, Silva said. They had to be raised from their silos to be launched, and then they had to be fueled, resulting in a 20-minute delay before launch.

Improvements were made, and the Titan II emerged. Titan II, Silva said, "had an increased payload, store-able propellants, and in-silo launch capability, allowing it to be deployed in less than a minute."

As for accuracy, it was expected that as crews gained experience, 90 percent of the missiles would hit their targets. That figure comes from a book recommended by Grunewald, Command and Control by Eric Schlosser. Subtitle of the 2013 book: "Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety." Everything you ever wanted to know, and more, Grunewald said, is in this book.

Titan II was, Silva said, "a quantum leap in ICBM technology," with a 6,000-mile range and a 30- to 35-minute flight time. It was thus virtually invincible.

Virtually, but not completely. A first strike by the Soviets might have rendered the Titans moot. Plus everything else around.

"Arkansas was a major, major target for the Soviet Union," Silva said.

The surrounding farm was owned by Ralph and Reba Jo Parish, whose home was about a third of a mile from the silo. The Parish family still owns the land. On hand at the history walk were several family members, including Mona Parish Harper, daughter of Ralph and Reba. (Mona Harper and her husband, Ben, gave Historic Preservation permission to put on the event.)

The Parish family sold a bit of land to the Air Force. Construction began in January 1961. Complex 374-7 was placed on alert, or activated, on Dec. 18, 1963.

Between alert status and the explosion, there were a few leaks of toxic gas, Silva said. The worst happened Jan. 27, 1978, when a leak created a toxic cloud 3,000 feet long, 300 feet wide and 100 feet high. Four people were hospitalized, local civilians were evacuated and some cattle died.

On the evening of Sept. 18, 1980, Ralph and Reba Jo Parish drove past the complex, Silva said. They saw white smoke. And the red warning light was on.

A state trooper advised the Parishes to get the whole family and go as far away as possible. They wound up in a hotel in Harrison. They came back late in the day Sept. 19, after the explosion. Their home, so close to the silo, was still standing.

Mona Parish Harper's most vivid memory?

"It was being scared and wondering if Mom and Dad would have a house when we got back," she said.

NEWSHOUNDS

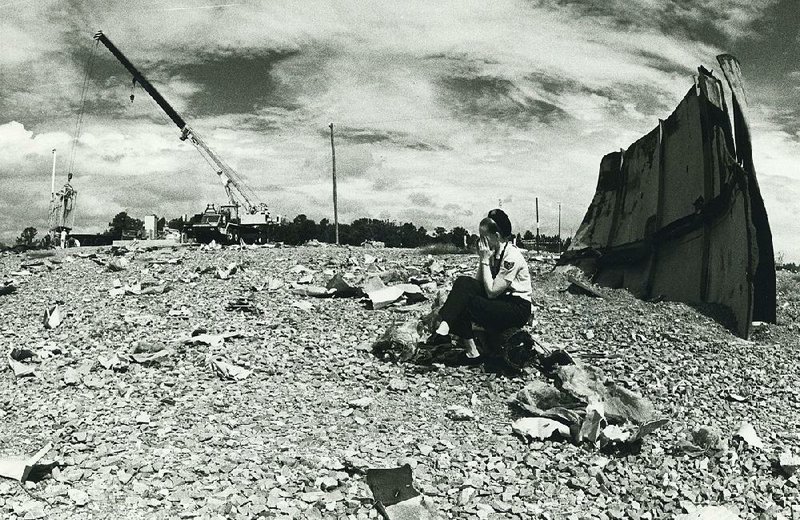

Steve Taylor was a police reporter for the Arkansas Democrat, working the 4 p.m. to midnight shift, when wire services reported a leak at Damascus. He and photographer Michael McMullan were instructed to book hotel rooms at Conway and head to Damascus.

"I happened to be the guy in the bullpen who got the call," he said, "a 20-year-old kid chasing ambulances and firetrucks."

Airmen had secured the site. At least a dozen vehicles driven by reporters, photographers and the TV stations lined the highway in the dark.

"It was kind of spooky," Taylor said. "Mostly we were talking among ourselves."

The airmen were mum.

"We weren't getting anything. I remember sitting up there thinking the folks in Little Rock were getting more information because they had a PIO [public information officer] on the phone, but no PIO was talking to us."

What a public information officer might have told the assembled press was that a maintenance team forgot to bring the right tool into the silo. Instead of going back for the proper 20-pound wrench, Grunewald explained, they used a substitute, unauthorized-wrench that was being used in the silo as a doorstop.

During a maintenance procedure, a 9-pound socket came off this wrench, fell between the platform and missile, and dropped 70 feet. Grunewald said the socket bounced off the thrust mount supporting the missile, then hit and punctured the Stage 1 fuel tank. Fuel, Grunewald said, gushed out.

THE EARTH SHAKES

At 3 a.m., about 10 hours after the socket was dropped, came the explosion.

Loitering on the highway, the knights of the keyboard had no clue.

"It was an absolute surprise," Taylor said. "Everybody was stunned. We hadn't been warned an explosion was imminent. You heard this loud thunderclap, a concussion we felt in our bodies, and we looked into the sky."

Taylor saw "this pink and orange fireball, flames shooting into the sky with burning concrete."

The 740-ton silo door was blown off. The warhead, Grunewald said, was blown 200 feet away into a ditch.

Most alarming, Taylor said, were the noxious fumes. His lungs burned. His eyes teared up.

All the airmen had on gas masks. The journalists? Not a chance.

"One airman pulled off his gas mask, said to go as far as you can as fast as you can," Taylor said, "and put his gas mask back on."

Taylor's car, a four-cylinder Honda, was pointed north. His hotel in Conway was south. But there was no inclination on his part to turn around. "By the time I got to Marshall, my heart had stopped beating so hard."

He'd driven about 45 miles as fast as that Honda could go.

Taylor found a pay phone at a Piggly Wiggly grocery store and called the city desk. The New York Post had called, too, and left a phone number. Taylor called the Post and gave a first-person account of his experience.

"I got $175 for it, and they butchered my story," he said. "Back then, that was more than a week's pay."

Grunewald spent 22 years in the Air Force. From 1974 to '79, he was a Titan II missile commander in Arkansas.

The Soviets were terrified of the Titan II, he said. Each missile's warhead, with its 9 megatons of explosive nuclear power, was 600 times more powerful than Little Boy, the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. And the Titan II was accurate to within a mile of its target.

"The Titan had more explosive power than all the bombs dropped in all the wars in history. That was the Cold War."

The Titans were dismantled from 1982 through '87, Grunewald said, and the last one to go off alert status was in Arkansas (at Judsonia). The Soviets watched via satellite as the silos were dismantled.

Someone in the crowd asked the question everyone wanted answered. Could the warhead have exploded?

"As bad as it was, the warhead was benign," Grunewald said. "It was never in danger of detonating."

Frank Fellone, deputy editor of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, was state editor of the Arkansas Democrat in September 1980.

ActiveStyle on 09/21/2015