The ability to provide clean, cheap drinking water is becoming a challenge across the United States, even in water-wealthy Arkansas.

Most of the nation's water systems were built in the first half of the 20th century with enormous public and private investment.

In places like Des Moines, Iowa, decades of little or no investment have resulted in a creaky 70-year-old water treatment plant that needs to be replaced and miles of cracked water mains that need to be repaired or replaced, according to a national infrastructure report by The Associated Press. It now also faces the need of installing costly, specialized equipment to treat water that it draws from the nitrates-polluted Raccoon River.

Finding the money to pay for water-system improvements is the challenge.

For most water systems, paying to repair and replace treatment plants and leaking pipes often means raising customers' water bills, and the amount of federal money available for such work is tiny when compared with the need nationally.

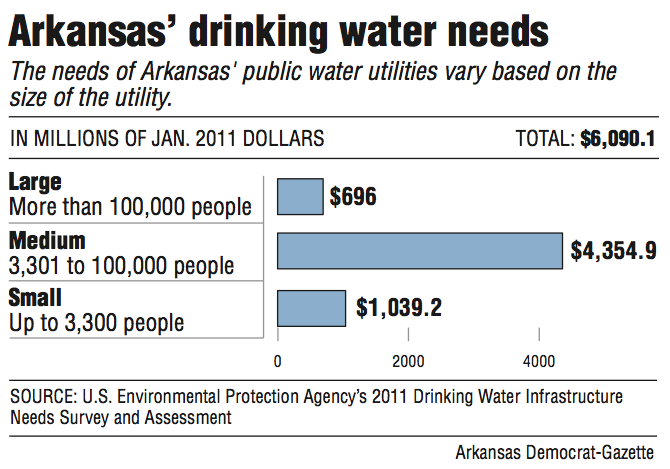

In Arkansas, the cost for needed water infrastructure expansion and improvements hovered around $6 billion in 2011, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

In large cities, the costs mean or have already meant rate increases to repay bank loans or for bond issues secured to fund large-scale water projects.

Officials with Arkansas' largest water utility, Central Arkansas Water, anticipate raising rates in the next 10-12 years to help address problems with pipes that are more than 100 years old.

The utility spends $1.4 million each year, replacing a couple of miles of pipes and relocating pipes to accommodate such things as new construction projects.

Officials want to increase that by $8 million to $10 million.

Replacing just 1 mile of pipes can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Central Arkansas Water has 2,300 miles of pipes, roughly the distance from Little Rock to Seattle.

The amount that customers have been paying for water in central Arkansas -- less than one-tenth of a penny per gallon -- "never fully covered the price of maintaining a water system," said Graham Rich, the utility's chief executive.

Central Arkansas Water serves 400,000 customers. To speed up its pipe replacements, officials anticipate that a bill of $13.10 per month, for example, would increase by $5 to $7.

Leaking money

Without maintenance, pipes can break, spilling water into the streets, or they can leak, slowly releasing water into the ground. Both can waste water that utilities have already paid to filter and pump.

The Arkansas Department of Health tracks such "water loss." It considers a loss of 20 percent or more significant.

Leaking pipes can also lead to water being contaminated before it reaches customers, although Arkansas officials say the water that utilities across the state supply is nearly free of contaminants.

Across the U.S., some large utilities have raised rates to fix old, leaky pipes, according to the AP report.

In the past couple of years, Philadelphia and New Orleans have raised rates to spend millions more annually on pipe replacements, and Los Angeles is debating rate increases to pay to speed up its pipe replacements.

In more rural areas, systems often must decide whether to keep patching their wasteful, breaks-prone pipes, or raise rates and repair them but at a much higher per-customer cost than what is paid in more-populated areas.

Most federal assistance for water systems comes in the form of loans from the EPA and the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Rural Services unit. Those loans often go to smaller systems that have no other way of obtaining loans.

Grant money is often limited and reserved for towns that are in dire need or too small to shoulder loans.

Eudora, in Chicot County, has a water-loss rate of 50 percent -- meaning 50 percent of the water it treats and pumps is lost before it reaches customers. The city received a $1,850,000 principal-forgiveness loan in July that it won't have to pay back and a $250,000 loan that it will have to pay back.

Eudora, in the state's far southeastern corner near the Louisiana and Mississippi state lines, had 2,819 residents in the 2000 U.S. Census. The Census Bureau estimated in 2014 that the population had shrunk to 2,137.

The Arkansas Natural Resources Commission, which administers the EPA loans within Arkansas, determines which places get them and which don't. Most requests are approved, Water Development Division Manager Mark Bennett said, but some are just not feasible.

The commission has proposed an Arkansas Water Plan in which it recommends that water and sewer systems develop plans for maintaining their pipes and treatment systems into the future.

The plans could include consolidating neighboring systems to reduce costs, something that would dilute communities' control over their local water systems.

According to the water plan drafted by the Natural Resources Commission in 2014, Arkansas needs $5.74 billion to build, maintain and improve its water-systems infrastructure over the next decade.

In fiscal 2014, the Natural Resources Commission awarded federal loans and grants totaling $86 million for dozens of water and sewer projects.

That funding could increase, Bennett said, because earlier this year the state Legislature raised the cap on bond issues.

But, small towns and those with shrinking populations are more likely to default on the loans as their populations shrink, leaving fewer people paying water bills, Bennett said.

A declining customer base is one of the biggest problems for water systems across Arkansas and challenges their abilities to borrow money, Arkansas Department of Health engineering director Jeff Stone said.

Small systems -- those with 3,300 or fewer customers -- face more than $1 billion in infrastructure needs.

Medium systems -- with 3,301 to 100,000 customers -- face more than $4.3 billion in infrastructure needs.

Forgotten underground

Hot Springs Utilities serves 70,000 customers in Garland County and spends more than $1 million each year replacing its old pipes. That money comes in part from rates that were raised a few years back.

The utility continues to battle main breaks, but it has fewer pipe leaks since it started its capital improvement projects, engineering project manager Larry Merriman said.

Nationally, the water infrastructure problems are most often because of years of neglect, Merriman said.

It's easy to forget about water pipes because they're buried and out of sight, he said.

"If you don't see it [water] come to the surface, then it doesn't become an issue." People notice problems when a pipe breaks and spills water into the street, he said.

That often means that the pipe is old, and officials then move it to the top of their replacement lists.

At Clarendon Waterworks, where old pipes led to a 40 percent water loss recorded in a 2013 inspection, Supervisor Steven Parrish spent all day Thursday fixing a broken water main.

He declined a reporter's request for an interview so he could finish repairing the main. He didn't return a message left for him Friday.

An Arkansas Department of Health Public Water Supply Sanitary Survey for the Clarendon system dated June 27, 2013, read "suspected losses are thought to be primarily old service lines and meters and perhaps the Master Meter readings."

Other than that and a separate valve issue, the report concluded, the system -- which serves 1,640 people in Monroe County -- was well-run, and met or exceeded all requirements for operation, monitoring, reporting and compliance.

In contrast, Jonesboro in east Arkansas is growing, leading Jonesboro City Water & Light officials to install more and newer pipes, decreasing the average age of the city's waterlines system.

Kevan Inboden, special projects administrator for the utility, estimated that 75 percent of the system has been installed in the past 50 years.

That water system serves about 85,000 customers, including several thousand people on the outskirts of town, Inboden said. Recent rate increases have helped pay for infrastructure changes to get the system in compliance with the federal Safe Drinking Water Act, he said.

In Northwest Arkansas, where the population is also growing, water rates have increased to accommodate the increase in customers and construction.

Beaver Water District -- which is the wholesale supplier of water to Fayetteville, Springdale, Rogers and Bentonville -- underwent a $104 million expansion of its withdrawal, treatment and pumping systems from 2003-09.

The district paid for about 40 percent of that work with cash reserves and the other 60 percent with the sale of water revenue bonds that required a water rate increase of $0.15 per 1,000 gallons sold.

Growth in the area, Chief Operating Officer Larry Lloyd said, has allowed the district to be more financially stable. Now, the district is building up its reserve fund so it can pay for future expansions without having to again sell revenue bonds.

"A lot of utilities aren't able to do that," Lloyd said.

Information for this article was contributed by Ryan J. Foley of The Associated Press.

SundayMonday on 09/27/2015