FAYETTEVILLE -- For many college students pursuing a career in science or engineering, one course in particular presents an early hurdle.

Calculus, the mathematics of change and motion developed in the mid-17th century, now often serves as a wet blanket thrown atop the aspirations of modern-day 18-to-24-year-olds.

"Across the board, Calculus I is very effective at decimating students' confidence, interest and enjoyment of mathematics," said Jessica Ellis, a Colorado State University researcher who's part of a team looking to improve calculus instruction at the college level.

Speaking last month at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, her deadpan remark drew a ripple of laughter from a crowd that included mathematics faculty and instructors. But the moment quickly passed as Ellis described a gender imbalance in outcomes after Calculus I, when about 1 in 6 women drop plans to continue with a sequence of calculus courses required for most engineering careers, compared with fewer than 1 in 8 men.

Rather than differences in ability, Ellis said student survey responses suggest a lack of confidence among women compared with men. She described the larger calculus research project as relevant given a looming workforce shortage in science and engineering, a concern that has also alarmed Arkansas leaders.

"We just need more students, whether they're boys or girls, to study math and science," said Suzanne Mitchell, executive director of the Arkansas Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) Coalition, a group that is in its second year of funding workshops for women and girls interested in STEM.

Ellis said experts such as the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology have identified a need for more STEM graduates to meet workforce demands. The council in 2012 issued a report calling for 1 million more STEM graduates over the next decade above the current rates of degree attainment.

In Arkansas, Gov. Asa Hutchinson has pushed for expanded high school instruction in computer science, and last year signed into law a mandate that computer-coding classes be taught in schools across the state. Hutchinson, in a prepared statement, said the focus on coding would lead to a workforce "that's sure to attract businesses and jobs to our state."

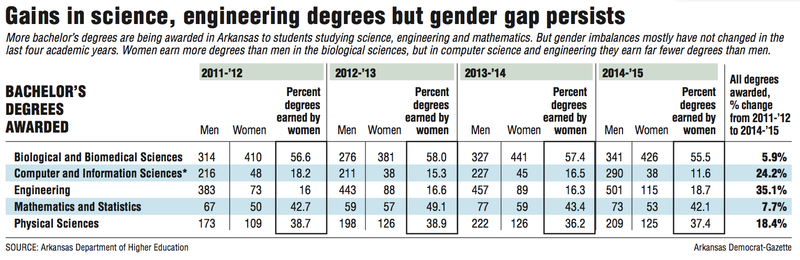

Yet the gender imbalance in Arkansas has been perhaps most striking in computer science.

Statewide, in the most recent academic year, men earned more than seven times as many bachelor's degrees as women in computer science. Men earned 290 computer sciences degrees in 2014-15 compared with 38 degrees earned by women, according to the Arkansas Department of Higher Education.

In engineering, men earned 501 bachelor's degrees compared to 115 earned by women in 2014-15, according to state data.

Imbalances can also be seen nationally as men earn the "vast majority" of bachelor's degrees in engineering, computer science and physics, according to a report from the National Science Board, though some fields such as the biological sciences have more women earning bachelor's degrees than men.

Calculus serves as a gatekeeper course for computer science as well as other STEM disciplines. Ellis is part of a research group taking on a national project launched by the Mathematical Association of America with funding from the National Science Foundation.

The association is seeking to identify the characteristics of successful programs in college calculus. The group's recommendations so far include offering support services that give students both academic and social connections.

Ellis said research over the years, taken as a whole, has conclusively found no differences in mathematical ability between men and women.

"I didn't enter this project looking to find differences between men and women in their experiences in Calc I," Ellis said.

But she said the disparity became clear while poring over responses to a national survey on student attitudes regarding calculus. About 2,000 students who were enrolled in Calculus I at various colleges and universities in 2010 turned in responses that allowed Ellis and other researchers to interpret the results.

The surveys allowed researchers to see women dropping out of the calculus sequence even if they reported similar preparedness and career goals as men. Based on answers to questions about teaching, Ellis said the gender imbalance stood out even when students had similar reports on the quality of their teacher and the type of teaching techniques used in class.

However, Ellis said one survey question highlighted a difference between male and female students: "I do not believe I understand the ideas of Calculus I well enough to take Calculus II."

Ellis said 32 to 35 percent of women answered "yes" to the question, compared with 14 to 20 percent of men.

Researchers did not track grades for all students, but among a group providing grade information, 42 percent of male students switching away from the calculus track earned an A or B grade in their Calculus I course. For women "switchers," Ellis said, 48 percent earned an A or B grade.

"Yet the women overwhelmingly said that they didn't think they understood the ideas well enough to go on to Calc II," Ellis said.

She said survey responses from the larger group suggest that women start in the Calculus I course with lower confidence in their mathematical abilities compared with men.

"All mathematically capable students are losing mathematical confidence over the course of Calc 1," Ellis said, with "switchers," as Ellis put it, experiencing a greater decrease in confidence.

"Women start at a lower confidence and are therefore ending at a lower confidence because they're experiencing the same decrease as men," Ellis said.

Ailon Haileyesus, a UA-Fayetteville engineering student, said the confidence level of a student is "definitely a big issue."

But Haileyesus, who works as a calculus tutor, said she did not believe that confidence levels could be so easily generalized according to a student's gender.

"I think that the motivation for continuing in classes comes from, I guess, your background and what you see as important," Haileyesus said. Words of encouragement can also play a vital role for some students, she said.

The Women's Foundation of Arkansas has hosted free events for girls promoting computer science and STEM education, with one free event held in December at the Governor's Mansion. Hutchinson spoke at what the group called a "coding summit" attended by 150 girls.

The University of Central Arkansas on April 22 is hosting Girl Power in STEM, an event for eighth-grade girls.

Mitchell said about 430 girls and women attended free events last year funded by the Arkansas STEM Coalition. A free STEM Leadership for Girls conference on April 22 at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock will allow upper high school and early college students to learn more about opportunities in science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

Mitchell said federal funds authorized under the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Act administered by the Arkansas Department of Career Education pay for the workshops.

She said she expects more than 600 girls and women to attend events this year exploring STEM.

"We're missing a lot of very smart girls who could contribute to career opportunities and careers that would help the economy of our state," Mitchell said.

Metro on 04/03/2016