TUNICA COUNTY, Miss. -- It's a Thursday, noted Liz Bahr, as she scanned the bar at Sam's Town Hotel and Casino -- the night was still young and two customers she had been serving had just left, leaving the craft beer bar empty.

And Thursdays don't see the influx of visitors looking to win big at the casino that Fridays and Saturdays do. Even the crowds on those nights are smaller these days, Bahr adds.

"For a lot of the time this was the Vegas of the South," the bartender said. "I remember making thousands a night."

Now, as the casino heyday in Tunica County has ended, Bahr's nightly earnings have been reduced to a few hundred dollars in tips, with a good night reaching between $300 and $500.

"A lot of people have left," said Bahr, who was preparing to leave the casino industry to open a salad truck. "They have moved out of town."

In Tunica County, home to eight casinos, the strike-gold opportunity expected to pull the rural Southern community out of poverty has seemingly fizzled, leaving some to question what the county has to show for it.

Despite the millions of dollars the development of lavish casinos brought in revenue over the past two decades, poverty still reigns in this Mississippi Delta community. And now the casino money is shrinking as the gambling industry flounders.

The casinos came to the county in the 1990s, sowing the expansive cotton fields near the Mississippi River with tall buildings and neon lights. Soon enough, they were as common in Tunica as plantations.

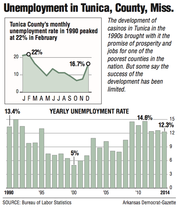

The arrival of the casinos brought the promise of jobs and prosperity to the county, which in the 1990s had one of the highest poverty rates in the county and an unemployment rate that reached above 20 percent.

"You're either the farmer or farm hand," Bahr said.

What happened here when the casinos came, and whether it was a success or failure, largely depends on whom you ask.

Tunica County officials say that while the business and revenue from the casinos has declined in recent years, investment in critical infrastructure -- made possible due to the casinos -- has positioned the county to attract more companies and broaden its economy.

But critics say that in the years since the casinos came to the area, county officials have wasted many millions of dollars and the opportunity for the community to prosper.

"It was like an economic perfect storm," said John Mohead. "But like a lot of success stories, it doesn't last."

Mohead owns Southbound Pizza, a trendy eatery in Helena-West Helena he hopes will be part of a downtown revitalization in the Arkansas city.

Thirty-two miles away in the town of Tunica, where Southbound Pizza initially opened, the prospect is bleaker. Instead of a restaurant bustling with customers, Mohead has an empty 6,000-square-foot building that blends with an environment of boarded-up shops and a closed gas station.

Mohead opened Southbound Pizza in 2013, but two years later he moved across the river because business slowed. And he says he knows of other business owners in Tunica who are also looking to make a move to Helena-West Helena.

"It's intriguing. It's always fun to be on the first wave of a renovation," Mohead said. "Helena has gone so far. ... I don't think there's anyway to go but up. In Tunica, you didn't have that. It was stagnant. The economy was stagnant."

There is a divide between blacks and whites in Tunica County, some say, and this ultimately influenced the way casino revenue was spent. For some, it is why the transformation of the county was limited.

More than 75 percent of Tunica County's 10,343 population is black. Until recently, the county's governing Board of Supervisors was exclusively white. Today, at least one member is black -- James Dunn. No one else on the board would respond to phone calls. The county collects a 4 percent tax on local casino revenue.

"For 15 years, there was around $40 million a year coming into the county," said Mil Duncan, Carsey School of Public Policy fellow at the University of New Hampshire. "The whites were in control of the politics and the spending of that $40 million. They invested in infrastructure -- better roads, the airport."

After the casinos came, the county was able to improve its roads, water and sewer systems, the local schools, along with the building of a golf course, Tunica Arena and Expo Center and a recreation center, said Webster Franklin, president and chief executive officer of the Tunica Convention and Visitors Bureau.

"The citizens of this area had other employment opportunities and we grew tremendously," he said, adding that the casinos "provided an infrastructure that we are still to this day seeing an advantage of."

"If it doesn't look like it's been here for 100 years, it was developed 20 years ago," Franklin said. "The saying is 'Rome wasn't built in a day.' If we grow over the next 20 years as we have the last 20 years, it will be a better place than it is today."

Yet, many say that despite this development, some plans originally established for the casino revenue never materialized.

"There were supposed to be all of the things," said John Fewkes, who used to hold a variety of jobs in Tunica but now works in Helena-West Helena. "Now that every other state has [gambling] and lottery ... there's nothing there to attract anybody."

Many black leaders wanted to use the casino money to invest in the community -- to provide parents and children with job skill training and education as a way to raise them out of poverty. But there was resistance to using casino revenue for that type of development, Duncan said.

"The problems are so deeply racially politicized," Duncan said. "The history of [Tunica] is for social isolation for African Americans. The white leadership wouldn't have thought about addressing poverty, per se. They were thinking economic development -- not capital development and helping those who are poor to escape poverty."

After the casinos came, the community was less divided, and the county's poverty and unemployment rate declined, Duncan said.

In 1989, Tunica County had a poverty rate of 56 percent, but by the 2000s it had been cut in half and it's now at 27.9 percent, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The decline in the poverty rate was a result of people coming from outside the community to Tunica to work in the casinos, and because some residents were able to take advantage of the opportunities offered by the casinos, Duncan said.

"The opportunities for employment for those who could take it was dramatic," she said. "Poverty declined as the casinos came in. Employment increased."

But now the casino industry in Tunica is floundering. In 2014, Harrah's Tunica Hotel and Casino closed, laying off more than 1,000 people. And as the industry struggles to attract customers, tax revenue is declining.

Casino revenue from the region in Mississippi that includes Tunica has dropped from about $1.6 billion in 2006 to $950 million in 2015, said Allen Godfrey, executive director of the Mississippi Gaming Commission.

Part of the decline is due to the rise of casino-type operations in other states, including in Arkansas, locals said.

"We only have about half the jobs we had at one time," said Dunn, the county supervisor.

After the casinos came, the county's unemployment rate dropped from more than 20 percent to single digits -- something that was "unheard of in the Mississippi Delta," he said. Now the rate is 10.7 percent

"With [gambling] and revenue generated, we were able to build infrastructure that was attractive to outside industry," he said.

But, he said, "We've got to do more."

Dunn and Webster say the development that has already occurred because of the casinos will allow the county to attract industries to the area now that the casino industry is declining. Others are not as optimistic about the prospects.

"There's nothing but farmland," Bahr said. "There's nothing at all."

SundayMonday Business on 04/10/2016