The Jewish holiday of Passover, which commemorates the Jewish people's escape from slavery in Egypt, began at sundown on Friday. The holiday is one filled with ritual and symbolism, and it's more than a simple remembrance. Jews are meant not just to retell the story of the exodus, but to experience it as if they were actually present.

The story of Passover is found in the book of Exodus. According to the biblical account, the Jewish people had been enslaved in Egypt for more than 200 years, toiling under various rulers until Moses was called on to save them.

Moses asked Pharaoh to free his people but he refused, even after God unleashed a series of plagues upon the empire -- turning water to blood and overrunning the country with frogs and swarms of locusts. Despite it all, Pharaoh still would not free the Jewish people. So God sent forth the final plague -- the death of all of Egypt's firstborn children.

The Jews, knowing what was to come, marked their doorways with lamb's blood as a sign for the angel of death to "pass over" their houses and spare their children. In the aftermath, Pharaoh finally gave in and freed the slaves, but even as they fled he tried to stop them. Moses, with God's help, divided the Red Sea that was barring their escape and they fled to freedom through the divided waters.

Rabbi Barry Block of Congregation B'nai Israel in Little Rock said Passover is a time to celebrate freedom.

"What's most important is that we celebrate that we were freed from slavery and we take from our being free a responsibility to free others," Block said. "We are taught to remember the heart of the stranger, for we were strangers in the land of Egypt. That's the most important teaching of Passover. We sit at the Seder table and reflect on our freedom and the call to freedom in the world today."

Block said Jews are to remember those still enslaved today and to work for their freedom -- whether they're victims of human trafficking

or "slaves" because of poverty, war or discrimination.

To commemorate their flight to freedom, Jews gather for a Passover Seder and to retell the story of the exodus. Some do this only on the first night of the holiday, and others have a Seder on the second night, too, depending on the particular branch of Judaism. The length of the holiday also depends on which tradition is followed. Some say Passover is seven days, as specified in the Torah, while others hold to an eight-day tradition.

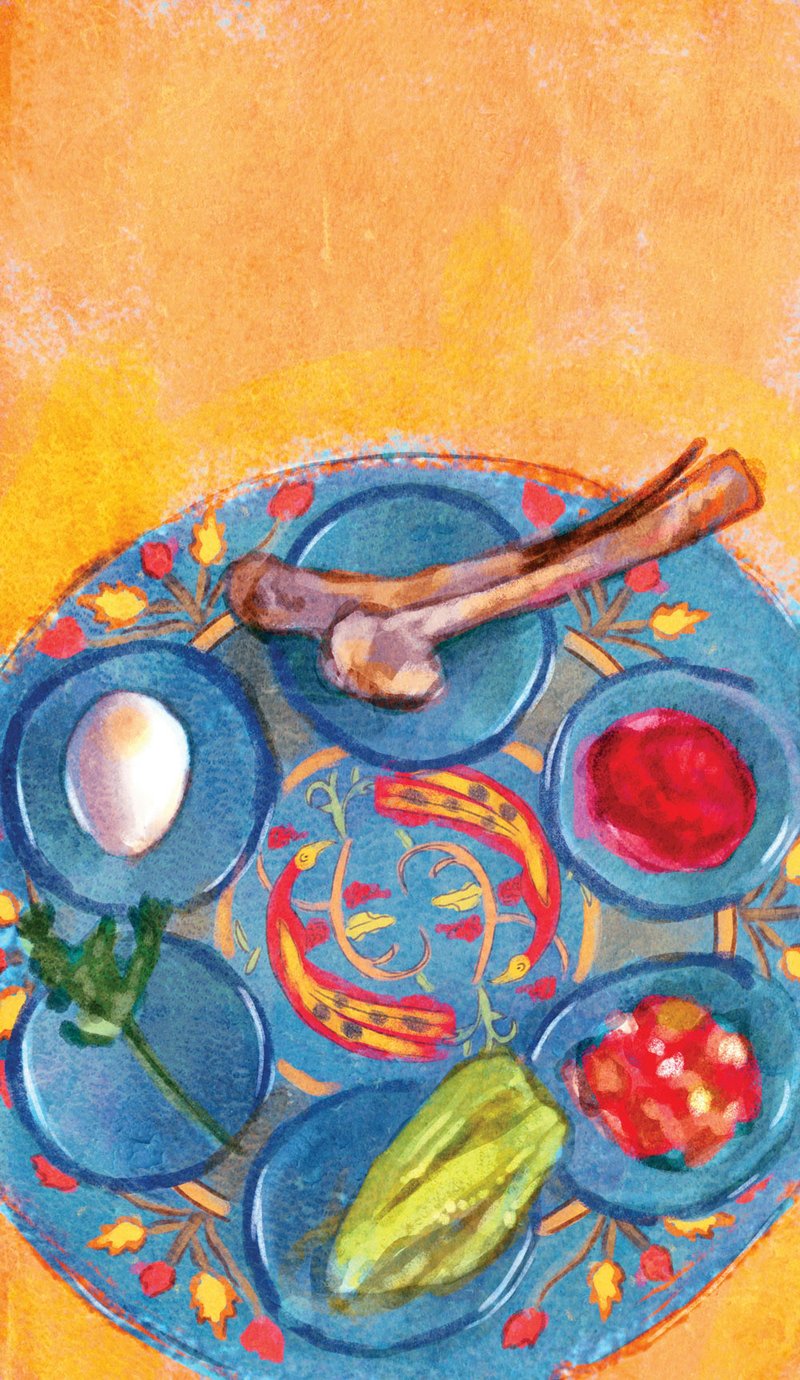

The Passover Seder is a sacred meal filled with symbolism. In the Reform tradition, the plate includes a shank bone (zeroa), which symbolizes the paschal lamb sacrificed during Passover; a hard-boiled egg (beitzah), a symbol of rebirth; bitter herbs (maror or chazeret), used to remember the bitterness of slavery (horseradish and lettuce are commonly used); a mixture of apples, nuts, wine and spices (charoset), meant to symbolize the mortar used by the slaves as they toiled in Egypt; and parsley (karpas), which is dipped in salt water to symbolize tears of the slaves. Matzo -- a flat, crackerlike bread -- and wine are also featured in the meal.

Block said matzo is the most important symbol of Passover. It's a dual symbol of the poor trapped in slavery and of freedom.

"Most think the significance is that it's the bread of freedom because when [the slaves] were freed from bondage they didn't have time for the bread to rise, but the main significance of matzo is it's the poor bread their ancestors ate in the land of Egypt," Block said. "It's another reminder that there are people in the world who don't have the blessing and food that we do."

In the days before Passover begins, Jewish homes are supposed to be rid of any leavened food, such as bread, cake and cookies and even flour, as a reminder of the trials of their ancestors when they were slaves.

Rabbi Kalman Winnick of Congregation Agudath Achim in Little Rock said the story of Passover is known as the "birthday of the Jewish people." He said a lesson can be learned from the Passover story and what happened when the Jewish people finally cried out to God for help.

"When they did, God answered," Winnick said. "Solutions are available whenever we are ready to call out. The answer is always within us but God can't help us until we are in a relationship with God and ask for help."

Winnick said no matter the circumstance, "We need to call out and realize we don't need to do it alone."

The lessons of Passover go beyond a once-a-year ritual. They are to be remembered each day in Jews' thrice-daily prayers as they sing a song about leaving Egypt.

"We mention the redemption that allowed us to be free to have an unencumbered relationship with God. It should be what we think about every day," Winnick said.

Winnick said Passover is also meant to be more than simply remembering the time of slavery.

"Each person is obligated to envision themselves as if they were the one leaving Egypt," he said. "It's not a history lesson. It's a personal experience for every person every year."

Rabbi Pinchus Ciment, executive director of Lubavitch of Arkansas in Little Rock, said his congregation has a Seder on the first two nights of Passover each year. They also commemorate the end of the holiday.

"This seventh day of Passover has many references and connotations toward the messianic era," Ciment said. "Ultimately the exodus was meant to bring a sense of completion and perfection to the world, with the Jewish people meant to be a lamp to the nations to bring the world to a perfect state of being."

So far, that hasn't happened, and Ciment said Jews still have work to do, which they reflect on each year at the closing of the holiday.

"The energy and thrust of the last days of Passover are much more a reflection on future redemption," he said. "It's like two bookends. One is to begin the process and the other is we have yet to complete that process. We are at the threshold but haven't done so yet. So the seventh and eighth days are looking forward to marking that completion."

Ciment said the Chabad-Lubavitch tradition includes a concluding Passover meal, as specified by the founder of the Hasidic movement, Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov. The concluding meal during his time was simply the eating of matzo, but years later the tradition of drinking four cups of wine, as done in the Seder on the first nights of Passover, was added.

"These matzo and wine reflect the completion, the ultimate liberation," Ciment said.

Ciment said the framework of the holiday is built around asking questions and understanding the symbolism behind Passover. He said the story of Passover should not be forgotten.

"We have the ability now to utilize the most precious gift which God has given mankind, which is time. While before we were enslaved we were limited, physically and mentally, in our capacity to do what we wanted. After the exodus God has granted us the ability to utilize time in ways in which we are in control of. That's the freedom," he said. "Once we choose to say it's not important that Passover happened, we are losing the meaning of having control of life now. Ultimately we are supposed to become active participants of maintaining this wonderful, beautiful world. If we say it doesn't make a difference, we are going back to that [slave] mentality."

Religion on 04/23/2016