Every week I start my Old News research by reveling in reading what the Arkansas Gazette had to say 100 years ago. So for today, I read the archive for Aug. 15, 1916.

A headline snags me; I realize it foretells events of titanic importance (World War I! Poliomyelitis! Women's suffrage!), and then I poke the archives for details to put that big history into context. "Context is public service," I think. "Knuckle down, lazy girl."

And every week I fall knuckles-first down a rabbit hole and wake up in Wonderland, giggling.

Look at this thing I found while researching something else (never you mind what). The Gazette reported it July 9, 1916:

"Get a Bigger Dog," Is City Collector's Advice

When Owners Complain That License Tags Are Too Wide for Small Collars of Pet Canines.

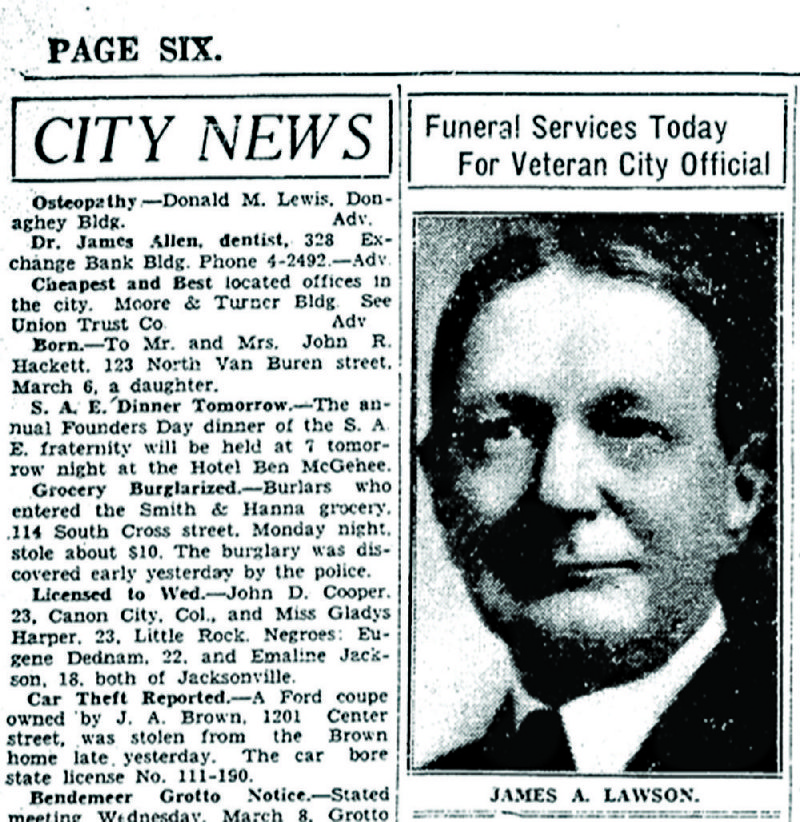

"'If your dog's collar is too small for the present aluminum dog license tag, get a larger collar, and if necessary, a larger dog,' is the advice of City Collector James Lawson, who is having his yearly tussle with the public over the style of dog licenses that he has selected.

"Mr. Lawson says the 1916 tag, which is made of aluminum and is two inches long and one inch wide, is the latest thing in license tags, and is in use in Paris and other cities. However the owners of small dogs, or dogs having narrow collars, object strenuously to the new tag because it scratches the neck of the dog by extending over the sides of the collar.

"Last year the tag was triangular in shape and dangled from the dog's collar like a watch charm. The owners of the French poodle and other diminutive canines did not object to this tag, but owners of hunting dogs raised a fierce protest because they said that the tags became entangled in brush and were extremely annoying to the dogs.

"The annual collection of dog licenses is a task which Mr. Lawson is prepared to admit is one of the most disagreeable he has to perform. The first trouble is the tardiness of many owners of dogs to purchase the tags, and the second difficulty is the securing of a wagon and starting it upon its rounds; not to mention the calls by anxious owners who find that their dogs have been taken up and are in danger of being killed."

TAGGED

City Collector James A. Lawson (1871-1933) belonged to two of Little Rock's oldest families. He was born in his maternal grandfather Charles G. Scott's home at 503 E. Sixth St. (about two blocks east of today's Scott Street). And

Lawson Road in southwestern Pulaski County led to his other grandparents' farm.

He was appointed by the City Council in 1911 unanimously by aldermen who were his former schoolmates. He was not employed to deal with dogs. The collector received and deposited fees for permits (electric, building, sidewalk, plumbing, circuses...), licenses (general business, saloons, peddlers ... dogs) and all assessments and levies, involuntary (road repair) and voluntary (library fund).

1916 was Lawson's fifth year of selling dog tags, and you can intuit from the tone above how the first four went.

People barked at him, told him puns, addressed him as "dog catcher," asked to pay the poll tax so their dogs could vote. Once, a man named Barkman arranged delivery to him of a telegram requesting a dog for the battleship Arkansas. Adorable children paid him in pennies. In May 1913, one headline about tags read, "Blood money pours in."

To be clear, his predecessor, City Collector Fred Kramer, also had trouble making the people pony up the annual $1.50 "dog tax" and, enforcing an ordinance apparently passed in 1909, also threatened them with dog catchers.

But Lawson took a stand -- and was surrounded by pranksters.

IMPLACABLE

Gazettes dating back to 1875 show Arkansas cities undergoing spasms of dog catching inspired by rabies. Backed by a state law dated that year, cities typically empowered police to shoot untagged dogs or poison them with strychnine-laced bread. During one rabies scare, any unmuzzled dog in Argenta was shot. Loose dogs were a menace, but strays and beloved pets ran together. Tags were an attempt to help police tell them apart.

It wasn't just rabies. In September 1912, the Gazette reported, "The activity of the Garbage Department in requiring refuse to be kept in closed vessels to await collectors, has made the food problem so serious a proposition for the homeless canine population that they prey on chicken coops and refrigerators." (Refrigerators were holes in the cool ground.)

From the Gazette's City News column, April 26, 1912: "May 1 is a black letter day on the dog calendar, as on this day the dog license becomes due."

May 25, 1912: "City Collector James Lawson yesterday submitted the names of about 1,500 owners of dogs in Little Rock to Police Chief Fred Cogswell, and the police will immediately round up all who have not paid license and order them into court. The chief said yesterday that old excuses such as 'Sorry, but Tray died last week,' and 'We sent Fido to the country day before yesterday,' will not serve this year."

Clearly, that threat didn't work.

July 28, 1912: "Dogs having no license tags after August 1 will be shot."

Sept. 14, 1912: "Little Rock is to have a dog-catcher. He will go forth next week in a screened wagon to gather in the canines whose masters do not regard them with sufficient affection to purchase a license tag from City Collector James Lawson."

Sept. 15, 1912: "That City Collector James Lawson means business with his dog-catching plan, was indicated yesterday when the old patrol wagon was washed and Chief of Police Fred Cogswell made arrangements to detail officers to accompany the screened wagon. All dogs which carry no license tags will be captured and killed, beginning Monday morning."

Sept. 17's paper brought news that the first day of the one-week patrol netted "30 mongrels" -- no "aristocratic dogs." In the old horse-drawn paddy wagon, Patrolman Ira P. Hoffman supervised four trusties from the city chain gang "armed with long poles surmounted by wire loops. These loops are thrown about the necks of the hapless canines and they are bundled into the wagon to be hustled to the jail" under the Auditorium on Markham Street. In theory, they had 10 days to live.

The terror of the roundup elicited compliance. "Also, it might be said," City News reported, "the plan has not been entirely free from trouble for Mr. Lawson -- he even has been abused over the telephone." One frantic lady tracked him by phone on a Sunday to the country club golf course, expecting him to rush to City Hall to accept her $1.50.

The Sept. 24 Gazette reported the patrol had penned 64 dogs under the Auditorium ... where Col. Theodore Roosevelt was scheduled to speak Sept. 25, after a parade in his honor.

Uh-oh.

But, remarkably, 63 of the 64 dogs had staged a jail break. City Attorney Harry Hale and Freg Isgrig, secretary to the mayor, appear to have accidentally on purpose discovered the hole, and Hale admitted he helped one little dog through. Certainly they found it hilarious.

By the 27th, 17 dogs were back in custody, and Lawson had Cogswell extend the roundup.

On the editorial page Oct. 10, 1912, the editor wryly reported that Paris was employing "men who can bark like dogs" to walk the city at night and bark for five minutes in front of every house -- to discover homes wherein unlicensed dogs were hiding. "There may be people who wouldn't put it beyond City Collector James Lawson to use men of the requisite mimetic ability in an effort to locate unlicensed dogs by means of counterfeit canine cacophony."

PUBLIC SERVANT

Lawson held office 22 years. By the '20s, Little Rock had a full-time dog catcher, and Lawson had less to do with the pound he and Cogswell created. The tag fee rose to $3 and became proof of annual rabies vaccinations administered at City Hall.

In 1931, the Gazette had a bit more fun at his expense when Lawson and his wife were dragged into the street by their 90-pound Great Dane, which didn't want to go into a veterinary clinic.

Because of all the assessments and permits he managed, his name continued to appear in print nearly daily -- until March 1933, when he died, unexpectedly, in his sleep. (Actually, his name went on appearing in legal notices for weeks after he died.)

He is buried in Mount Holly Cemetery.

Next week: World War I! Poliomyelitis! Women's suffrage!

ActiveStyle on 08/15/2016