PESCARA DEL TRONTO, Italy -- As the search for survivors ground on, Premier Matteo Renzi pledged new money and measures Thursday to rebuild quake-devastated central Italy.

A day after the deadly quake killed at least 250 people, a magnitude-4.3 aftershock sent up plumes of thick gray dust in the hard-hit town of Amatrice. The aftershock crumbled already cracked buildings, rattled residents and closed already clogged roads.

It was only one of the more than 470 temblors that have followed Wednesday's pre-dawn quake.

The string of aftershocks left homeless residents and rescuers on edge.

"Here it comes," said one volunteer rescue worker, bracing herself as a tremor hit the city shortly after 1:30 p.m. Thursday.

Firefighters and rescue crews using search dogs worked in teams around the hard-hit areas in central Italy, pulling chunks of concrete, rock and metal from mounds of rubble where homes once stood. Rescuers refused to say when their work would shift from saving lives to recovering bodies, noting that one person was pulled alive from the rubble 72 hours after the 2009 quake in the nearby town of L'Aquila.

"We will work relentlessly until the last person is found, and make sure no one is trapped," said Lorenzo Botti, a rescue team spokesman.

"We keep on digging," Amatrice Mayor Sergio Pirozzi told Italy's state broadcaster, RAI.

But he also suggested that hope was fading. "You ask me if there is news on whether there are people who could still make it," Pirozzi said. "Since last night, no."

Rescuers still raced to conduct searches. Italy cheered as a 10-year old girl was pulled from the rubble alive 17 hours after the quake.

The main earthquake, measured by the U.S. Geological Survey as a magnitude-6.2 temblor, struck at 3:36 a.m. Wednesday and was centered about 100 miles northeast of Rome.

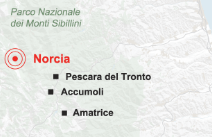

Worst affected by the quake were the towns of Amatrice and Accumoli near Rieti, 60 miles northeast of Rome, and Pescara del Tronto, 15 miles farther to the east.

The roads leading to Amatrice remained clogged with caravans of firetrucks, diggers, ambulances and sundry rescue vehicles waiting for orders Thursday. A row of drab gray tents lined a field on the town's edge, doubling as a morgue.

Outside, a small crowd of residents waited for names to be called. "They're identifying the dead," one police officer said.

Some sobbed, while others clutched at one another for support.

Pirozzi, Amatrice's mayor, spent part of the morning in the makeshift morgue.

"The identification has to be done right away -- it's hot," said Giancarlo Carloni, the town's deputy mayor.

Many were left homeless by the scale of the destruction, their homes and apartments declared uninhabitable. Some survivors, escorted by firefighters were allowed to go back inside homes briefly Thursday to get necessities for what will surely be an extended absence.

"Last night we slept in the car. Tonight, I don't know," said Nello Caffini as he carried his sister-in-law's belongings on his head after being allowed to go quickly into her home in Pescara del Tronto.

Caffini has a house in nearby Ascoli, but said his sister-in-law was too terrified by the aftershocks to go inside it.

"When she is more tranquil, we will go to Ascoli," he said.

Charitable assistance began pouring into the earthquake zone in traffic-clogging droves Thursday. Church groups from a variety of Christian denominations, along with farmers offering donated peaches, pumpkins and plums, sent vans along the one-way road into Amatrice that was already packed with emergency vehicles and trucks carrying search dogs.

"We've seen incredible solidarity, closeness, love, help from all of Italy," with even the country's struggling municipalities offering funds, said Carloni, the deputy mayor. "It makes me proud to be an Italian."

Other assistance was spiritual.

"When we learned that the hardest-hit place was here, we spoke to our bishop and he encouraged us to come here to comfort the families of the victims," said a priest who gave his name only as Father Marco as he walked through Pescara del Tronto. "They have given us a beautiful example, because their pain did not take away their dignity."

Italy's civil protection agency said the death toll had risen to 250 by Thursday afternoon, with more than 180 of the fatalities in Amatrice. At least 365 others were hospitalized, and 215 people were pulled from the rubble alive since the quake struck. A Spaniard and five Romanians were among the dead, according to their governments.

There was no clear estimate of how many people might still be missing, since the rustic area was packed with summer vacationers. The Romanian government alone said 11 of its citizens were missing.

In Pescara del Tronto, rescue crews were looking Thursday for three people believed crushed in a hard-to-reach area.

"The dogs from our dog rescue unit make us think there could be something," said Danilo Dionisi, a spokesman for the firefighters.

Emergency services set up tent cities around the quake-devastated towns to accommodate the homeless, housing about 1,200 people overnight. In Amatrice, 50 elderly people and children spent the night inside a sports facility.

"It's not easy for them," said civil-protection volunteer Tiziano De Carolis, who was helping to care for the homeless in Amatrice. "They have lost everything: the work of an entire life, like those who have a business, a shop, a pharmacy, a grocery store."

Emergency funding

Renzi authorized a preliminary $56.4 million in emergency funding and the government canceled taxes for residents, pro-forma measures that are just the start of what will be a long and costly rebuilding campaign.

"The credibility and honor of us all will be in granting a true reconstruction that allows the residents to live and restart," he said.

And the Culture Ministry said Thursday that all income generated from state museums Sunday would be used to help provide relief in areas battered by the earthquake. The minister of culture and tourism, Dario Franceschini, urged Italians to go to museums to show solidarity with those affected by the quake.

Renzi also announced a new initiative, "Italian Homes," to answer years of criticism over shoddy construction across the country, which has the highest seismic hazard in western Europe.

Yet Italian officials were coming under fire for failing to do more to reinforce the ancient cities and towns across the earthquake-prone country.

Renzi said that it was "absurd" to think that Italy could build completely quake-proof buildings.

"It's illusory to think you can control everything," he told a news conference. "It's difficult to imagine it could have been avoided simply using different building technology. We're talking about medieval-era towns."

Those old towns do not have to conform to the country's anti-seismic building codes. Making matters worse, those codes often aren't applied even when new buildings are built.

Armando Zambrano, the head of Italy's National Council of Engineers, said the technology exists to reinforce old buildings and prevent such high death tolls when quakes strike every few years. While he estimated that it would cost up to $105 billion to reinforce all of the historic structures across the country, he said targeted efforts in the riskiest areas could be done for less.

"We are able to prevent all these deaths. The problem is actually doing it," he said. "These tragedies keep happening because we don't intervene. After each tragedy we say we will act but then the weeks go by and nothing happens."

Some experts estimate that 70 percent of Italy's buildings aren't built to anti-seismic standards, though not all are in high-risk areas.

Funding shortfalls and bureaucracy are obstacles to making the country's buildings quake-resistant. A new law tries to encourage homeowners to make their homes earthquake-proof by reimbursing 65 percent of the cost over 10 years, but it isn't enough to push Italians, who are facing years of economic stagnation, to put up the cash to make the upgrades.

Compounding the problem, many of the oldest and most vulnerable structures are in remote villages inhabited mostly by retired Italians getting by on pensions with no cash to spare. In the cities, upgrades are stifled by the condominium-style rules of buildings requiring the agreement of multiple owners for such investments.

"We're among the best in the world in managing emergencies," Renzi said, praising the men and women, many of them volunteers, who jump into action when crises hit. "But it's not enough to be in the vanguard in emergencies."

Geologists surveyed the damage Thursday to determine which buildings were still habitable, while Culture Ministry teams were fanning out to assess the damage to some of the region's cultural treasures, especially its medieval-era churches.

Survivors began to focus on the challenges ahead. Towns such as Accumoli, a small 12th-century town of nearly 700 about 91 miles northeast of Rome, already faced years of decline. Despite pledges to rebuild, residents feared that their lives would only get worse.

Lucia Di Gianvito, a 57-year-old house cleaner who lost her home in the quake, said she had no word from the elderly woman who employed her.

"She is probably dead," Di Gianvito said."Everything is going to be over now. No jobs. No shops left. It's over."

A woman nearby chimed in, saying the town would rebuild. But Di Gianvito laughed.

"The situation wasn't good even before," she said, adding that only one of her two adult sons had managed to find work. "There were no jobs. The young people are leaving. Should we leave, too? Maybe. But where will we go? There is no hope."

Information for this article was contributed by Trisha Thomas, Frances D'Emilio, Nicole Winfield and Vanessa Gera of The Associated Press; by Elisabetta Povoledo, Elaine Allaby, Dan Bilefsky, Gaia Pianigiani and Kit Gillet of The New York Times; and by Stefano Pitrelli and Anthony Faiola of The Washington Post.

A Section on 08/26/2016