It is a truism to say that comedy comes from misery. Clowns are depressed, fueled by anxieties and neuroses. To be funny you have to present something true and to present something true you have to confront the awful emptiness at the world's core. You have to stare down the absurdity of creation.

In 1944, when future Monty Python member Graham Chapman was 3 years old, a Royal Air Force plane -- a Douglas C-47 -- exploded in the air near the town of Wigston Magna, in Leicestershire, England. Chapman's father was a policeman in the town, and Chapman's earliest memory was of crew members' body parts laid out in the garden behind his house.

"[O]ne can clearly see a lung hanging down from the lower branches of a chestnut tree, a leg on the front lawn, and a hole in the roof of a semi-d[etached house], which was later explained by a lady who came out of the house carrying a bucket with what looked like liver in it," Chapman wrote in his 1980 memoir A Liar's Autobiography (the anecdote is reprinted in 2003's The Pythons Autobiography). "The 3-year-old boy is not particularly worried, because he is holding his mummy's hand and his daddy is in charge, and being very efficient about trying to sort human flesh into at least nine different sacks. Unfortunately there seem to be only eight heads and no other suspicious roof-holes."

Chapman goes on, turning this macabre nightmare into a typically Pythonesque skit, with his unruffled mother interrupting her husband's gruesome work to inform him that she's taking their child shopping and to ask if she should bring him his tea.

"What? Oh yes, eggs on toast please," he answers distractedly. "Left arm here, anyone missing a left arm?"

"We haven't got any eggs. There's a war on."

"Ask Harold. Something's bound to have fallen off the back of a lorry."

"All right, dear. Come on, Graham, stop staring at all that blood, it won't do you any good."

FROM THE ASHES OF WAR

Americans and the English speak almost the same language, but there are fundamental differences in the ways we perceive the world. In the middle of the last century, we were allies in a great war we experienced very differently. Pearl Harbor notwithstanding, the American homefront was insulated from the war. Meanwhile bombs were falling all over the United Kingdom.

John Cleese was nearly a year old when German planes bombed Weston-super-Mare, the small seaside resort where he lived, in August 1940.

"Most Westonians were confident the raid had been a mistake," Cleese wrote in his 2014 autobiography So, Anyway. "The Germans were a people famous for their efficiency, so why would they drop perfectly good bombs on Weston-super-Mare, when there was nothing in Weston that a bomb could destroy that could possibly be as valuable as the bomb that destroyed it?

"... The Germans did return, however, and several times, which mystified everyone. Nevertheless I can't help thinking that Westonians actually quite liked being bombed: it gave them a sense of significance that was otherwise lacking from their lives."

Eric Idle was born in 1943 in Harton, in northeast England. His first memory was "of a Wellington bomber crashing in flames" next to his nursery school. Idle's father, an RAF tail gunner, survived the war but was killed while on his way home for Christmas in 1945. "I remember Christmases with my mother weeping by the tinseled tree for my father," Idle wrote in The Pythons Autobiography.

Michael Palin was born after the bombing of Sheffield in 1941, but he remembers ration books and the air raid shelter he played in. Welshman Terry Jones was 4 years old before he met his father, stationed in Scotland during the war.

Terry Gilliam, on the other hand, was born in Minnesota and grew up in Los Angeles. He had an uneventful childhood and was voted "most likely to succeed" and prom king in his high school.

BRING OUT YOUR DEAD

The Pythons were children of war, traumatized in modern ways. This goes a long way toward explaining the fatalism and surrealism baked into their brand of silliness. Seeing the neighbor lady with an airman's liver in a bucket is bound to warp you, or at least make you question the presence of a benign and interventionist God.

What came out of that Blitz-born generation -- a lot of those kids playing in the rubble of their neighbors' houses under the blank, thousand-yard stares of demobbed Tommies while their mums fingered coupon books? The U.S. boomed after the war, but in battered Britain rationing continued into 1954. Still, similar if not perfectly analogous youth cultures emerged in both countries in the postwar era. In America, the "teenager" was largely an invention of advertising, a demographic target with income to dispose. In Britain, there were "Teddy Boys," working-class youth affecting the fashions of their Edwardian grandparents. In America, there was Chuck Berry and, later, Elvis. In England, there were the paler imitations (Wee Willie Harris, Tommy Steele) and ultimately the sturdy Cliff Richard.

Many of the Teds were young men old enough to have served in the war, whose tastes and influences were largely set in the prewar era. But it was the war children -- the Pete Townshends, John Lennons, Ray Davieses, et al. -- who gave British rock an intellectual, nihilistic bang.

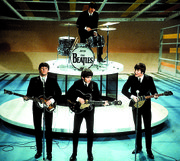

British rock is largely an echo of American rhythm and blues -- what we're hearing is a bunch of English kids trying to sound like Howlin' Wolf and failing in a kind of glorious, junky way. (Later we'd get American garage bands attempting to sound like the English kids trying to sound like American blacks.) But we're also hearing an applied intelligence beyond the American greasy kids stuff brand of rock 'n' roll. After all, it took Dave Davies to shove knitting needles through his amp's speakers to give us "You Really Got Me." There's a different quality to even the earliest post-skiffle British rock. Even the cute, apple-cheeked Beatles had a deeply subversive side.

Remember the train sequence in A Hard Day's Night (1964) when a middle-aged, upper-class businessman (Richard Vernon, head of the Bank of England in Goldfinger) enters the boys' compartment and engages the lads in pointed repartee? At one point he tells them he "fought the war for your sort."

"Bet you're sorry you won," Ringo replies.

That's not the sort of joke you'd here in the United States, even today.

ANYTHING BUT MINDLESS GOOD TASTE

In a sense, The Beatles ended on Sept. 20, 1969, when John Lennon, responding to Paul McCartney's suggestion that the band try to reinvigorate itself by playing small clubs under pseudonymous names, told his mates he wanted "a divorce" before driving off with Yoko Ono.

Monty Python's Flying Circus premiered on the BBC about three weeks later.

Sometimes called the Beatles of comedy, the Pythons were similarly self-contained, capable of writing and performing their own material. It's difficult to imagine that ensemble comedy shows like The Simpsons, South Park, 30 Rock or Saturday Night Live would exist in the same form were it not for the Pythons. Their influence is incalculable.

They were also like The Beatles in the way they were, at first at least, highly collaborative: The Lennon-McCartney partnership was echoed by two Python writing teams -- one comprising Cleese and Chapman, the other Palin and Jones. Idle generally wrote alone, which makes him George Harrison in this analogy. Gilliam was primarily the troupe's animator.

But unlike The Beatles, the Pythons were not working-class -- Chapman, Cleese and Idle all studied at Cambridge (Chapman eventually earned his M.D. at St. Bart's Hospital); Palin and Jones at Oxford. Gilliam graduated from Los Angeles' Occidental College (the school Barack Obama attended from 1979 to 1981).

Nor were they an immediate success on this side of the Atlantic. Part of the first season aired in Canada in 1970, but it was soon dropped. Time-Life, which held the U.S. broadcast rights to BBC programs, deemed the show too British for American tastes. It wasn't until August 1972, with the release of And Now for Something Completely Different, a theatrical film made up of clips from the first two BBC seasons, that any Python material made it to the United States.

That film, which features several now classic sketches -- "Dead Parrot," "Upperclass Twits," "Nudge Nudge, Wink Wink" and "The Lumberjack Song" -- was a box office disappointment in the United States. It wasn't until October 1974, when more than 100 PBS stations across the country picked up the series, that Monty Python actually became a thing in the U.S. By that time, Cleese had demanded his own Lennon-like divorce from the group; the BBC series ended after three seasons and a truncated, Cleese-light fourth.

But that wasn't the end of Python. Between production on the third and fourth seasons, the group decided to make a "proper" feature, one that contained all new material and didn't rely on recycled clips. Based on the Arthurian legend, 1975's Monty Python and the Holy Grail enticed Cleese back into the band, as he felt they were breaking new ground. Jones and Gilliam took on directing, with Jones handling the actors and Gilliam contributing animated linking passages and the credits. Chapman, regarded as the best dramatic actor in the group, took on the lead role as King Arthur, with the other members (including Gilliam) playing various parts.

For a lot of people who didn't experience the Monty Python's Flying Circus TV series in the '70s, Holy Grail is where a lot of Americans first caught on to the Python's fiercely intelligent silliness. After more than 40 years, it holds up. It is worth mentioning that Holy Grail was partly financed by rock groups such as Pink Floyd, Jethro Tull and Led Zeppelin and British music industry entrepreneur Tony Stratton-Smith (founder and owner of Charisma Records, for which the Pythons recorded comedy albums).

Spamalot, the musical comedy adapted ("Lovingly ripped off," promotional materials read ) from the film by Idle and musical collaborators Neil Innes and John Du Prez, is not exactly wholeheartedly endorsed by the rest of the troupe. Gilliam has called it Python-lite and Jones once said it was "pointless" (although he later said he enjoyed watching a production). Palin admitted to being "hugely delighted" the show was going so well ("because we're all beneficiaries!"), but allowed "It's not 'Python' as we would have written it."

Cleese thoroughly approved of it at first, in part because he was paid a weekly royalty for having recorded the voice of God used in the production. But in 2011, Idle stopped paying Cleese because, Idle said, his former troupemate "had too much money already." Idle re-recorded the voice of God himself.

Cleese responded with a tweet: "I see Yoko Idle's been moaning (again) about the royalties he had to pay the other Pythons for Spamalot. Apparently he paid me 'millions'."

Chapman isn't around to have an opinion, having died in 1989, and providing Cleese with an opportunity to deliver one of the greatest, and most profane eulogies ever delivered.

IT'S JUST A FLESH WOUND

American comedy often seems like an angry thing; the howl of wounded beasts like Lenny Bruce, Richard Pryor and Mort Sahl or the passive aggressions of Woody Allen and Judd Apatow. But British humor has a different flavor. It's more intellectual, sillier and, at its heart, at least as dark.

Monty Python, the Kinks and Pink Floyd all crawled from the rubble of wartime England. They had seen with their own young eyes the way the world comes apart. It informed them in the way that luckier children who grew up far from war zones would never know.

They had seen the horror at the heart of the world; they could never unsee it.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

blooddirtangels.com

Style on 08/28/2016