HARDAN, Iraq -- Five graves arranged at the foot of Sinjar Mountain hold the bodies of dozens of minority Yazidis killed in the Islamic State group's bloody onslaught in August 2014. They are a fraction of the mass graves the extremists have scattered across Iraq and Syria.

RELATED ARTICLES

http://www.arkansas…">Kurd-Turk fighting in Syria dies down http://www.arkansas…">Top planner killed in Syria, ISIS says

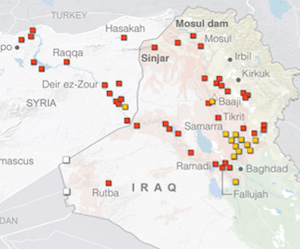

In interviews, photos and research, The Associated Press has documented and mapped 72 of the mass graves, with many more expected to be uncovered as the Islamic State group's territory shrinks.

In Syria, the news agency has obtained locations for 17 mass graves, including one with the bodies of hundreds of members of a single tribe all but exterminated when the extremists took over the tribe's region.

For at least 16 of the Iraqi graves, most in territory too dangerous to excavate, officials do not even guess the number of dead. In others, the estimates are based on memories of traumatized survivors, Islamic State propaganda and what can be gleaned from a cursory look at the ground.

[VISUAL GUIDE: Maps, satellite imagery and first-person accounts of Islamic State mass graves]

Still, even the known numbers of victims buried are staggering -- from 5,200 to more than 15,000.

Satellites offer the clearest look at massacres such as the one at Badoush Prison in June 2014 that left 600 inmates dead. A patch of scraped earth shows the likely site, according to photos obtained by the imagery intelligence firm AllSource Analysis and shared with the AP.

Of the 72 mass graves documented, the smallest contains three bodies; the largest is believed to hold thousands, but no one knows for sure.

On Sinjar Mountain, Rasho Qassim drives daily past the mass grave in Hardan that holds the bodies of his two sons.

The sites are roped off and awaiting the money and the political will for excavation. The evidence they contain is scoured by wind and baked by sun.

"We want to take them out of here. There are only bones left. But they said, 'No, they have to stay there, a committee will come and exhume them later,'" said Qassim, standing at the flimsy protective fence.

The Islamic State made no attempt to hide its acts. But proving what United Nations officials and others have described as an ongoing genocide will be complicated as the graves deteriorate. The Islamic State targeted the Yazidis for slaughter because it considers them heretics. The Yazidi faith has elements of Christianity and Islam but is distinct.

"There's been virtually no effort to systematically document the crimes perpetrated, to preserve the evidence," said Naomi Kikoler, who recently visited for the Holocaust Museum in Washington. The graves are largely documented by the aid group Yazda.

Through binoculars, Arkan Qassem watched it all. His village, Gurmiz, overlooks Hardan and the plain below. When the jihadis swept through, everyone in Gurmiz fled to the mountaintop. Then Arkan and nine other men returned with light weapons, hoping to defend their homes.

The first night, a bulldozer's headlights illuminated the killing of a group of handcuffed men. Then the machine plowed over their bodies.

Over six days, the fighters killed three more groups -- several dozen each, most of whom usually had their hands bound. Once, the extremists lit a bonfire, but Arkan couldn't make out its purpose.

Two years later, the 32-year-old has returned home, living in an area dotted with mass graves.

"I have lots of people I know there, mostly friends and neighbors," he said. "It's very difficult to look at them every day."

Nearly every area freed from Islamic State control has uncovered mass graves, like one found near a stadium in Ramadi. The graves are easy enough to find, most covered with just a thin coating of earth.

"They are beheading them, shooting them, running them over in cars, all kinds of killing techniques, and they don't even try to hide it," said Sirwan Jalal, the director of Iraqi Kurdistan's agency in charge of mass graves.

No one outside the Islamic State has seen the Iraqi ravine where hundreds of prison inmates were killed. Satellite images of scraped dirt along the river point to its location, according to Steve Wood of AllSource. His analysts triangulated survivors' accounts and began systematically to search the desert according to their descriptions of that day, June 10, 2014.

The inmates were separated by religion, and Shiites had to count off, according to accounts by 15 survivors gathered by Human Rights Watch.

"I was number 43. I heard them say '615,' and then one ISIS guy said, 'We're going to eat well tonight.' A man behind us asked, 'Are you ready?' Another person answered 'Yes,' and began shooting at us with a machine-gun," according to the Human Rights Watch account of a survivor identified only as A.S. The 15 men survived by playing dead.

Justice has been done in at least one mass killing by the Islamic State -- that of about 1,700 Iraqi soldiers who were killed by machine gun at Camp Speicher. On Aug. 21, 36 Islamic State militants were hanged for those deaths.

But justice is likely to elude areas still under Islamic State control, even when the extremists film the acts themselves. That's the case for a natural sinkhole outside Mosul that is now a pit of corpses. And in Syria's Raqqa province, where thousands of bodies are believed to have been thrown into the al-Houta crevasse.

Conditions in much of Syria remain a mystery. Activists believe there are hundreds of mass graves in Islamic State-controlled areas that can be explored only when fighting stops. By that time, they fear, any effort to document the massacres, exhume and identify the remains will become infinitely more complicated.

Working behind Islamic State lines, Syrians informally have documented some mass graves, even partially digging some up. Some of the worst have been found in the eastern province of Deir el-Zour. There, 400 members of the Shueitat tribe were found in one grave, just some of the up to 1,000 members of the tribe believed to have been massacred by the Islamic State group when the militants took over the area, said Ziad Awad, the editor of an online publication on Deir el-Zour called The Eye of the City, who is trying to document the graves.

In Raqqa province, the bodies of 160 Syrian soldiers, killed when the Islamic State overran their base, were found in seven large pits.

So far, at least 17 mass graves are known, though largely unreachable, in a list put together from interviews with activists from Syrian provinces still under Islamic State rule as well as fighters and residents in former Islamic State strongholds.

"This is a drop in an ocean of mass graves expected to be discovered in the future in Syria," Awad said.

Information for this article was contributed by Balint Szlanko, Salar Salim, Sinan Salaheddin, Zeina Karam, Philip Issa and Maya Alleruzzo of The Associated Press.

A Section on 08/31/2016