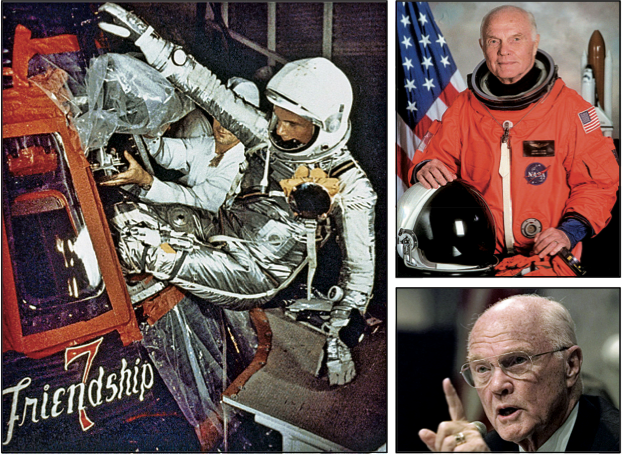

WASHINGTON -- John Glenn, whose 1962 flight as the first U.S. astronaut to orbit the Earth made him an all-American hero and propelled him to a long career in the U.S. Senate, died Thursday. The last survivor of the original Mercury 7 astronauts, he was 95.

John Glenn in Arkansas: 2004 visit to Museum of Discovery

COLONEL GLENN ROAD: How a Little Rock road came to be named after astronaut John Glenn

Glenn died at the James Cancer Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, where he had been hospitalized for more than a week, said Hank Wilson, communications director for the John Glenn School of Public Affairs.

"John always had the right stuff, inspiring generations of scientists, engineers and astronauts who will take us to Mars and beyond -- not just to visit but to stay," President Barack Obama said in a statement.

"Today we lost a great pioneer of air and space in John Glenn," President-elect Donald Trump said on Twitter. "He was a hero and inspired generations of future explorers."

Later, during a visit to the Ohio State University campus, Trump again extolled Glenn. "To me he was a great American hero, a truly great American hero."

John Herschel Glenn Jr. had two major career paths that often intersected: flying and politics, and he soared in both of them.

Before he gained fame orbiting the world, he was a fighter pilot in two wars. And, as a test pilot, he set a transcontinental speed record. He later served 24 years in the Senate from Ohio.

His long political career enabled him to return to space in the shuttle Discovery at age 77 in 1998, a cosmic victory lap that he relished and turned into a teachable moment about growing old. He holds the record for the oldest person in space.

More than anything, Glenn was the ultimate and uniquely American space hero: a combat veteran with an easy smile, a strong marriage of 70 years and nerves of steel. Schools, a space center and the Columbus airport were named after him. So were children.

In 1957, the Soviet Union leaped ahead in space exploration by putting the Sputnik 1 satellite in orbit and then launched the first man in space, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, in a 108-minute orbital flight on April 12, 1961. After two suborbital flights by Alan Shepard Jr. and Gus Grissom, it was up to Glenn to be the first American to orbit the Earth.

"Godspeed, John Glenn," fellow astronaut Scott Carpenter radioed just before Glenn thundered off a Cape Canaveral launch pad, now a National Historic Landmark, to a place America had never been. At the time of that Feb. 20, 1962, flight, Glenn was 40 years old.

During the four-hour, 55-minute flight, Glenn uttered a phrase that he would repeat frequently throughout his life: "Zero G, and I feel fine."

"It still seems so vivid to me," Glenn said in a 2012 interview on the 50th anniversary of the flight. "I still can sort of pseudo feel some of those same sensations I had back in those days during launch and all."

Glenn's ride in the cramped Friendship 7 capsule had its scary moments. Sensors showed that the spacecraft's heat shield was loose after three orbits, and Mission Control worried that he might burn up during re-entry when temperatures reached 3,000 degrees.

As Friendship 7 was descending, all radio contact was lost. Shepard, acting as "capsule communicator" from Cape Canaveral, tried to reach Glenn in his spacecraft, saying, "How do you read? Over."

After about 4 minutes and 20 seconds of silence, Glenn could finally be heard: "Loud and clear. How me?"

"How are you doing?" Shepard asked.

"Oh, pretty good," Glenn casually responded, later adding, "but that was a real fireball, boy."

In an era when fear of encroaching Soviet influence reached from the White House to kindergarten classrooms, Glenn, in his silver astronaut suit, lifted the hopes of a nation. When he emerged smiling from the Friendship 7 capsule after returning from space, cheers echoed throughout the land.

"You had to have been alive at that time to comprehend the reaction of the nation, practically all of it," author Tom Wolfe, who coined the phrase "the right stuff" to describe Glenn and the other Mercury astronauts, wrote in a 2009 essay. "John Glenn, in 1962, was the last true national hero America has ever had."

Arkansans remember him

Arkansans were among those remembering Glenn upon his death Thursday.

"He was an iconic figure, a John Wayne-like hero, except he was grounded in Midwestern values," said Mack McLarty, a former White House chief of staff who knew and admired Glenn for decades.

Although he had orbited the planet, Glenn remained down-to-earth, McLarty said. "He had an authenticity and people trusted him. They liked John Glenn. They respected him."

Glenn's accomplishments during the space race and later in the U.S. Senate were impressive, McLarty said. "I think he leaves a remarkable and enduring mark ... and history will judge him quite favorably. It will be an enduring legacy."

Democratic Party of Arkansas chairman Vince Insalaco invited Glenn to Arkansas in the early 1980s to deliver a speech at the party's 1982 Jefferson Jackson Dinner, an annual fundraiser that Insalaco was organizing.

Glenn, a Democrat, let them know that he wouldn't be needing a plane ticket, and his arrival was low key. "He'd flown himself in. He'd flown his little prop plane."

Locally, Glenn's name graces a street in Little Rock. Colonel Glenn Road off Interstate 430 in west Little Rock is named for him.

"Once called Upper Hot Springs Highway, Colonel Glenn Road was named in the 1960s for John Glenn," according to a March 23, 2003, article in the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

The name was changed because Upper Hot Springs Highway was often confused with Old Hot Springs Highway, also called Stagecoach Road, according to a March 3, 1962, article in the Arkansas Gazette.

Pulaski County's County Judge Arch Campbell was considering a new name for the roadway when Glenn orbited the Earth, the 1962 article said. Campbell, an aviation enthusiast, according to the article, suggested that the road be renamed in honor of Glenn, and residents embraced the idea.

Insalaco said that in 1982, after he picked up Glenn, he drove along I-430 and took the Colonel Glenn Road exit ramp. Glenn wanted to stop and look around, Insalaco said.

Before he left the city, admirers gave Glenn one of the road signs emblazoned with his name.

"He was a really great man. He just really was," Insalaco said.

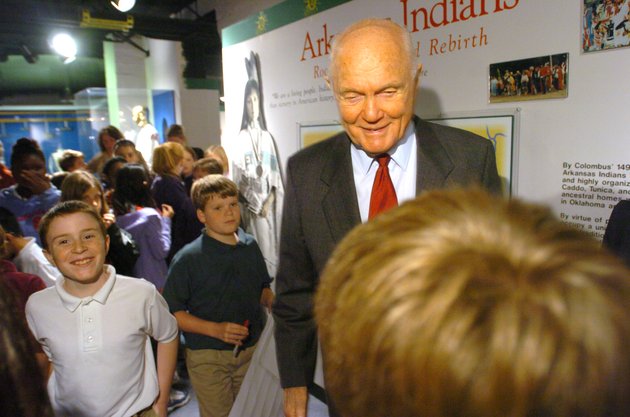

Beth Nelsen, program coordinator of the Museum of Discovery in Little Rock, remembers when Glenn visited the museum in November 2004.

She said Glenn's visit was in conjunction with the opening of the Clinton Presidential Center.

"I was blown away," Nelsen said. "He was so gracious. The feeling of just excitement that you felt from him. And the fact that he wanted to inspire young people just gave me shivers."

She continued: "I felt he really was inspirational. I can see why he went into politics and did the things that he did after he left the space program. I really believe he felt he had a mission to encourage young people to seek for much higher than just what's around them, to dream dreams."

Nelsen said Glenn connected with children at the museum.

"I've seen a lot of people talk over children. He talked to children," she said.

Sen. John Boozman, R-Ark., in a statement, called Glenn "an inspiration to us all."

"His contributions will live on in American history forever," he said.

Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., paid tribute to Glenn on his Twitter page, posting: "John Glenn 1921-2016, Rest in Peace to an American hero."

His life and times

Glenn was born July 18, 1921, in Cambridge, Ohio, and grew up in New Concord, Ohio. His love of flight was lifelong. John Glenn Sr. spoke of the many summer evenings he arrived home to find his son running around the yard with outstretched arms, pretending he was piloting a plane.

The younger Glenn's dream of becoming a commercial pilot was changed by World War II. He left Ohio's Muskingum College to join the Naval Air Corps and soon after, the Marines.

He became a successful fighter pilot who conducted 59 hazardous missions, often as a volunteer or as the requested backup of assigned pilots. A war later, in Korea, he earned the nickname "MiG-Mad Marine."

In 1943, Glenn married his childhood sweetheart, Anna Margaret Castor. They had two children, Carolyn and John David.

In later years, the couple divided their time between Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio. Both served as trustees at their alma mater, Muskingum College. Glenn spent time promoting the John Glenn School of Public Affairs at Ohio State University, which also houses an archive of his private papers and photographs.

Glenn's public life began when he broke the transcontinental airspeed record, bursting from Los Angeles to New York City in three hours, 23 minutes and eight seconds. With his Crusader averaging 725 mph, the 1957 flight proved that the jet could endure stress when pushed to maximum speeds over long distances.

In New York, he got a hero's welcome -- his first ticker-tape parade. He got another such parade after his flight on Friendship 7.

He first ran for the U.S. Senate in 1964 but left the race when he suffered a concussion after slipping in the bathroom and hitting his head on the tub. He tried again in 1970 but was defeated in the primary.

For the next four years, Glenn devoted his attention to business and investments that made him a multimillionaire. In 1974, Glenn again ran for the Senate and won.

He represented Ohio in the Senate longer than any other senator in the state's history. He became an expert on nuclear weaponry and was the Senate's most dogged advocate of nonproliferation. He was the leading supporter of the B-1 bomber when many in Congress doubted the need for it.

Glenn said the lowest point of his life was in 1990, when he and four other senators came under scrutiny for their connections to Charles Keating, the notorious financier who eventually served prison time for his role in the costly savings-and-loan failure of the 1980s. The Senate Ethics Committee cleared Glenn of serious wrongdoing but said he "exercised poor judgment."

He announced his impending retirement in 1997, 35 years to the day after he became the first American in orbit, saying, "There is still no cure for the common birthday."

Glenn returned to space in 1998 aboard the space shuttle Discovery. NASA tailored a series of geriatric-reaction experiments on Discovery to create a scientific purpose for Glenn's mission. He got to move around aboard the shuttle for nine days, far longer than the less than five hours in 1962. He also got to sleep on board and experiment with bubbles in weightlessness.

Glenn and his Discovery crewmates flew 3.6 million miles, compared with 75,000 miles aboard Friendship 7.

In a news conference from space, Glenn said, "To look out at this kind of creation out here and not believe in God is to me impossible."

Bill Clinton, who was U.S. president at the time, issued a statement Thursday, along with Hillary Clinton, mourning Glenn's passing.

"I will never forget seeing him off at Cape Canaveral, and emailing him during the mission," the statement read. "He was always eager to learn and embrace new ideas to improve lives. I was fascinated to see how young people were drawn to him, to his quiet dignity, open mind, and open heart. How lucky we were to have him so long."

As significant as his second spaceflight and his political career were, it is the mission in February 1962 for which Glenn will be most remembered.

"People are afraid of the future, of the unknown," he said in 1962. "If a man faces up to it and takes the dare of the future, he can have some control over his destiny."

Information for this article was contributed by Seth Borenstein of The Associated Press; by Dan Hart and Laurence Arnold of Bloomberg News; by Matt Schudel of The Washington Post; by Frank E. Lockwood, Jake Sandlin and Bill Bowden of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette; and by Gavin Lesnick of Arkansas Online.

A Section on 12/09/2016