The Arkansas Supreme Court has upheld lower court decisions to certify classes in two circuit court lawsuits over royalties paid by a natural-gas company operating in the Fayetteville Shale.

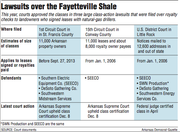

The class-action lawsuits -- known as Stewmon v. SEECO, et al, and Snow v. SEECO Inc. -- claim to represent thousands of Arkansas property owners who signed natural-gas drilling leases with S̶o̶u̶t̶h̶e̶r̶n̶ ̶E̶l̶e̶c̶t̶r̶i̶c̶ ̶E̶q̶u̶i̶p̶m̶e̶n̶t̶ ̶C̶o̶.̶ Southwestern Energy Exploration Co.*, a subsidiary of Southwestern Energy Co. A third class-action lawsuit, in federal court -- Smith v. SEECO, et al -- claims to represent Arkansans and others who are out of state, and its class was certified earlier this year.

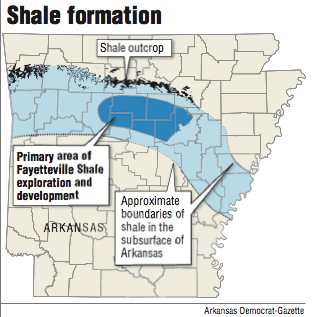

The leases were signed during the natural-gas drilling boom in the Fayetteville Shale, which stretches from the Mississippi River to western Arkansas. The boom went bust when natural-gas supplies grew and prices dropped.

Tim Holton, the attorney in the Stewmon case, said he plans to ask the judge in his case to approve notices to send out to class members and to set a trial date in the case.

A reporter attempted, without success, to contact attorneys in the Snow and Smith cases.

The company's attorneys argued in each case that Southwestern Energy was allowed to deduct any "reasonable" costs from royalties that were incurred through the sale of gas.

Southwestern Energy released a statement Wednesday to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette saying the company was still fighting the three lawsuits.

"Southwestern is defending these actions vigorously, as it believes all amounts it has deducted comply fully with the controlling lease provisions," the statement, sent by spokesman Christina Fowler, said.

The cases are some of the numerous lawsuits that have been filed in recent years in Arkansas over whether people who leased mineral rights to natural-gas companies were adequately compensated according to their contracts. Such lawsuits have become common nationwide, including in Pennsylvania, Texas, Oklahoma, Ohio and Louisiana. Some cases have been settled in Arkansas and other states.

Many of the lawsuits contend that natural-gas companies -- including the shale's biggest companies, Southwestern Energy Co., XTO Energy and BHP Billiton, which purchased Chesapeake Energy's assets in the shale -- have withheld payments improperly in a variety of ways from people who signed leases. Those ways, according to the suits, include charging too many fees, such as for services through subsidiary companies.

Southern Electric Equipment Co. (known as SEECO), DeSoto Gathering Co. and Southwestern Midstream Services -- all subsidiaries of Southwestern Energy Co. -- are the defendants in the Stewmon case.

"The corporate structure of these three entities is purposefully commingled and intertwined to permit the Defendants to buy and sell services from each other, with commensurate 'mark ups' or profits derived from these sales and purchases," the Stewmon complaint reads.

SEECO is the only defendant in the Snow case. In the federal Smith lawsuit, the defendants are Southwestern Energy subsidiaries SEECO, SWN Production (an alternate name for SEECO), DeSoto Gathering and Southwestern Energy Services Co.

The Supreme Court unanimously upheld the classes in the Stewmon and Snow cases on Dec. 8.

In the Stewmon case, Justice Josephine Hart wrote the opinion affirming the class certification by now-deceased 1st Circuit Judge L.T. Simes. She was joined by Justice Robin Wynne and Special Justices Bob Estes, Scott Richardson and M. Scott Willhite. Justice Rhonda Wood, joined by Chief Justice Howard Brill, wrote a concurring opinion. Justices Karen Baker, Paul Danielson and Courtney Goodson recused from the case.

In the Snow case, Wynne wrote the opinion affirming the class certification by 15th Circuit Judge Terry Sullivan. Wynne was joined by Hart, Estes, Richardson and Willhite. Brill and Wood again concurred, and Baker, Danielson and Goodson again recused.

court ruling in Snow

In SEECO's appeal of the Snow class certification, attorneys challenged the circuit court's decision to limit the class to Arkansas residents.

In his affirming opinion, Wynne wrote that circuit courts have broad discretion on classes and that the Supreme Court would not grant or deny a class unless it could identify abuse of that discretion.

In her concurring opinion, Wood wrote that she believed the certified class could be confirmed but that she was troubled by the case.

"I write to point out that this class action might have significant manageability problems going forward," Wood wrote. "The crux of this problem lies with the class definition, which needlessly limits the class to citizens of Arkansas."

The class allows for Arkansans who co-own leases with people who live outside the state, Wood wrote, which could cause the circuit court to re-evaluate the class.

"It is clear to me that the definition was designed to keep this case out of federal court," Wood continued. "While the plaintiff is the captain of its case, this should not exclude all other considerations. I am troubled that the circuit court allowed this consideration to guide its class-certification order. The best practice is to ignore these forum-shopping concerns and instead focus on efficiency, which at any rate is the primary purpose of the class-action mechanism."

Wood and Brill concurred in the court's decision on the Stewmon case for the same reasons.

court ruling on Stewmon

In their appeal of the Stewmon case, SEECO's attorneys argued that, among other things, the class definition was flawed and that competing lawsuits should be eliminated. They were referring to cases other than the Snow lawsuit.

Stewmon's attorneys argued that SEECO's claim about competing lawsuits was beyond the scope of what was being appealed. The Supreme Court agreed, noting in its Dec. 8 opinion written by Hart that it "will not entertain" issues other than the class certification.

The Supreme Court also concluded that the class definition identified clear, objective criteria for who would be covered: an Arkansas resident who signed a gas lease with SEECO by Sept. 27, 2013. That is the date the Stewmon case was filed.

The high court also rejected SEECO's argument that Stephanie DeVazier -- daughter of the now-deceased Sara Stewmon, who filed the lawsuit -- was not properly appointed as class representative. DeVazier was approved in March 2016 by Circuit Judge Kathleen Bell.

details of the suits

The three suits allege SEECO improperly reduced payments to property owners who had leased mineral rights to the company or a subsidiary.

Eldridge Snow and M.L. Tester sued in Conway County Circuit Court in 2010; Sara Stewmon sued in St. Francis County Circuit Court in 2013; and Connie Jean Smith sued in federal court in Little Rock in 2014. Smith lives in Oklahoma but owns property in the Fayetteville Shale.

The Snow and Stewmon cases limited their classes to people with Arkansas addresses.

Stewmon sought to represent about 11,000 property owners. Stewmon's class was certified in September 2014.

The Snow case class was certified in October 2014 to represent people who had leases on or after Jan. 1, 2006, which plaintiff's attorneys had estimated in filings to be about 11,000 leases and about 8,000 royalty owner payees.

Smith's federal case initially limited itself to people outside Arkansas who own property in the state and entered leases with Southwestern Energy and four subsidiaries.

In December 2015, Smith's attorneys -- in response to U.S. District Judge Billy Roy Wilson's rejection of the first proposed class -- pitched an "alternative" class that added Arkansas residents who had leases after Jan. 1, 2006. It was certified in April by U.S. District Judge Brian Miller, who had taken over the case. An expert for Smith estimated that Arkansans had signed more than 10,000 applicable leases and out-of-staters had signed more than 6,000. Earlier this year, SEECO sent out notices to 12,600 addresses.

SEECO's attorneys did not oppose the class certified in the Smith case.

Holton, the attorney in the Stewmon case, said he'd never heard of a federal case being certified while a state case's class was on appeal before the Supreme Court.

According to a Dec. 2 filing in the Smith case, 601 people opted out of being class members by the Nov. 11 deadline set in that case. That means they could seek damages as class members in Stewmon or Snow if they are Arkansas residents.

Arkansas residents who did not opt out of Smith still could be class members in Stewmon or Snow, legal experts say. Class members are people who may seek damages from the company if a judgment is made against the company or if a settlement is reached in the case.

In a related matter, DeVazier, from the Stewmon case, sued the lawyers for Smith and SEECO earlier this year, alleging that they would not adequately represent her or her fellow class members because of attempts by Smith's attorneys to settle the class-action cases without consulting the class members.

Attorneys for SEECO, representing themselves, and attorneys for Smith said Stewmon's attorneys were not invited to mediation because of expectations that the Stewmon lawsuit would be tossed out of court and because of Stewmon's attorneys' "penchant for needless disruption" that would doom the possibility of reaching a settlement.

U.S. District Judge Kristine Baker dismissed the case, saying DeVazier's claim of potential injury was "too speculative."

effects of one case on others

Going forward, legal experts say having multiple cases representing many of the same people could have an impact on each other, even if they proceed separately.

"This is generally what we call a 'race to judgment,'" said Theresa Beiner, associate dean and professor of civil procedure at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law.

If the federal case is resolved first, that could bind anyone who didn't opt out of it to that case, Beiner said. If a state case is resolved first, that could bind all Arkansas residents to the state case, leaving the federal case to represent only out-of-state residents, she said.

The defendants could ask a judge to stay the other cases while one proceeds, Beiner said.

Typically, lawsuits that seek to represent the same classes are combined into one case, said Joshua Silverstein, a professor at the Bowen School of Law who has worked on class-action cases. Often those cases that are combined are all federal cases or all state cases. State and federal courts have different rules for class certification, he said.

Having three cases pursuing the same claims and representing many of the same people could be problematic if one case is settled or decided before the other, which Silverstein said is "virtually inevitable."

A resolution in another court case "can have a binding impact on a related case with the same parties," Silverstein said.

"That's one of the reasons the cases are always consolidated," he said.

Both Beiner and Silverstein said they had never seen a situation like the one in the SEECO cases.

"That doesn't mean it doesn't happen," Beiner said.

A Section on 12/24/2016

*CORRECTION: The Southwestern Energy Co. subsidiary SEECO Inc. stands for “Southwestern Energy Exploration Co.” A previous version of this story in incorrectly referenced a different SEECO Inc.