"Baseball is what we were, and football is what we have become."

-- Mary McGrory

Today is Super Bowl Sunday, a corporate secular holiday that, like Christmas, is inescapable. Even atheists, agnostics and those who only refer to the sport as "American football" are forced to acknowledge the magnitude of the event. You don't have to be observant, you don't have to tune in or pay attention -- you can even mock it by receiving it as a camp ritual or turning your attention to the expensive commercials or the inevitable counterprogramming ("it's Puppy Bowl Sunday!") -- but you just have to hear about the Super Bowl.

And this is Super Bowl 50 in the official nomenclature. That's a change in protocol, the Super Bowl L. The National Football League has been using Roman numerals since Super Bowl V in 1971, a pretentious habit they decided lent the proceedings a bit of class. But the prospect of Super Bowl L seemed typographically unpromising, as "L" is an awkward, unfinished-looking letter that invites unwelcome alliteration. L is for loser, lame and laughable. The NFL cannot have that.

The NFL generally gets what it wants in today's America. In the otherwise less-than-interesting Will Smith movie Concussion, there's a nice bit where Albert Brooks, playing a

real-life guy named Dr. Cyril Wecht (who ought to have a movie made about his life) is trying to explain to Dr. Bennet Omalu (Smith) why his research -- which basically indicates that football is a dangerous, gladiatorial sport in which the players risk injuring their brains -- is unwelcome.

He points out that Omalu has run afoul of "a corporation that on a weekly basis has 20 million people craving their product -- the same way they crave food. The NFL owns a day of the week, the same day the church used to own. Now it's theirs. They're very big."

Big enough that their gravity warps everything. Concussion was supposed to send shock waves through the culture. In the end, Smith didn't even get nominated for an Academy Award. While it's probably inevitable that the NFL will take measures to make the game "safer," to do what it can to assuage the fears of mothers who might otherwise not want their babies to grow up to be Cowboys or (to use a word that's acceptable only in this particular context) Redskins. But the average NFL fan can't spell chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), and is more concerned about the "sissification of America" than whether head-hunting cornerbacks can expect to live to see L.

...

Football has been America's game for a long time for a couple of very simple reasons. First, it is a game made for television. As soon as TV -- as opposed to radio or live attendance -- became the way most Americans consumed their sports, the more kinetic, easier-to-parse football was bound to overtake baseball as our most popular spectator sport.

Secondly, it is, as comedian George Carlin noted, a martial game. On Oct. 11, 1975, on the very first episode of Saturday Night Live, Carlin delivered a version of what would become one of his signature routines, a bit on the differences between baseball and football.

"Football wants to be the No. 1 sport, the national pastime," Carlin said. "And I think it already is, really, because football represents something we are ... when you get right down to it, we're Europe Jr. We play a European game ... 'Let's take their land away from them!' ... Ground acquisition .... football's a ground acquisition game. You knock the crap out of 11 guys and take their land away from them. Of course, we only do it 10 yards at a time. That's the way we did it with the Indians -- we won it little by little. First down in Ohio -- Midwest to go!"

Carlin went on to point out that while baseball was a 19th-century pastoral game, football was a 20th-century technological struggle.

"In football, you wear a helmet; in baseball, you wear a cap," Carlin continued. "Football is played on an enclosed, rectangular grid, and every one of them is the same size; baseball is played on an ever-widening angle that reaches to infinity, and every park is different! .... The object in football is to march down field and penetrate enemy territory, and get into the end zone; in baseball, the object is to go home! 'I'm going home!'"

Baseball is also slow, a game someone once said you could watch while reading a newspaper. It is difficult to play, and hard to explain. Baseball makes a fetish of nuance, and we are not a nuanced people.

While football is possibly more complex than baseball, it's easy to get a sense of the objective of the game, to tell who's winning. (In truth, unless you're a professional coach who spends hours every day breaking down film and watching what happens away from the ball, you probably don't know that much about football.)

Football on television is especially reductive -- while the camera loves spectacle and balletics, the game is largely won by behemoths pushing at other behemoths, fighting for inches of turf.

...

Football's seminal moment came in the first nationally televised game, the 1958 NFL Championship between the Baltimore Colts and New York Giants, played in the original Yankee Stadium, also known as "The House that [Babe] Ruth Built." The Colts won in thrilling fashion, in sudden-death overtime, when on third down Baltimore quarterback Johnny Unitas stuck the ball in the gut of halfback Alan "The Horse" Ameche, who plunged into the end zone from one yard out.

The game, which took place three days after Christmas, is still widely cited as "the greatest ever played," although in reality it was a fairly sloppy contest played in cold conditions. There were fumbles, interceptions, botched plays.

But there were also compelling story lines. This was the game that cemented the myth of Unitas as an unflappable field general and -- until the rules were changed to allow passers like Dan Fouts, Joe Montana, Dan Marino, Tom Brady, Drew Brees and Peyton Manning to pile up extraordinary statistics -- the leading candidate for best quarterback of all time. Playing with three broken ribs, Unitas threw 40 passes in the game, an unreal total for the era. On the Colts' final drive in regulation, he completed seven straight passes while using less than 90 seconds on the game clock to set up a game-tying field goal with seven seconds remaining.

And there was a controversial call in the fourth quarter, where the Giants' halfback and future CTE sufferer Frank Gifford (the game's first matinee idol largely on the exposure gained here) seemed to have gained enough for a first down that would have clinched the game. In all, 15 future pro football Hall of Famers played or coached in the game, which was seen by an estimated 45 million Americans (even though it was blacked out in New York), most of whom would always remember where they were when Ameche crashed over the goal line.

The impact was immediate. Mere hours after the game ended, Ameche appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show (the bookers had approached Unitas first, but he passed the gig -- and the $300 talent fee -- on to his teammate).

And in Houston, Lamar Hunt, the son of oil billionaire H.L. Hunt, who had been thwarted in an attempt to buy an NFL franchise, decided to start his own league, what would become the American Football League.

Decades later, Hunt told his biographer, Michael McCambridge: "[T]he '58 Colts-Giants game, sort of in my mind, made me say, 'Well, that's it. This sport really has everything. And it televises well.' And who knew what that meant?"

There were 12 NFL teams when the Colts beat the Giants in 1958. By the start of the 1960 season there were 21. In 1966, a merger -- largely driven by the prospect of television money and the specter of a bidding war for star players -- between the leagues was announced. They'd continue to play their respective schedules -- and honor existing TV contracts -- until 1970, when they'd become one league with two divisions. But they immediately started deciding a world champion of American football, with an exhibition contest they were calling "the AFL-NFL World Championship Game," but that was referred to colloquially, even in the official game radio broadcast, as the "Super Bowl."

...

In the first two Super Bowls, the Green Bay Packers, that squad of legends led by Vince Lombardi, easily handled the AFL representatives -- Hunt's Kansas City Chiefs and the Oakland Raiders. It seemed that the junior league was overmatched.

That all changed on Jan. 12, 1969, when the New York Jets met the Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III (as it is known in retrospect). The Colts went into the game a prohibitive favorite. On the morning of the game, the line in Las Vegas was the Colts would win by 17.5 points.

While there were other interesting things about that game -- the Jets were coached by Weeb Ewbank, the same man who had coached the Colts over the Giants in the 1958 title game -- what everybody remembers is that three days before, the Jets' quarterback, a brash 25-year-old named Joe Namath, "guaranteed" a Jets victory. But though the Jets backed up Namath's words and the quarterback came away with the game's Most Valuable Player award, he hardly played a spectacular game. In today's parlance Namath might be said to have "managed" the game. He took few chances. He threw no interceptions, but he threw no touchdown passes, and he didn't throw the ball a single time in the fourth quarter. The Jets got by with one touchdown -- on a four-yard plunge by Matt Snell -- and three field goals.

The Jets' defense won the game. They intercepted Earl Morrall -- Unitas' backup who'd played the entire season after the legend had been injured in the final pre-season game, led the Colts to a 13-1 record and was named the MVP of the 1968 season -- three times. (Note to Hollywood: Earl Morrall also deserves a bio-pic.)

When the 35-year-old Unitas came off the bench to replace Morrall in the third quarter, he led the Colts to a touchdown. The Colts recovered the onside kick after the score and were driving late in the game. He hit three straight passes and it looked as though the Colts were about to score again when Unitas' former teammate, Jets cornerback Johnny Sample, snapped the spell by breaking up a pass. On the next play Unitas was sacked. On fourth down, he was hurried and threw the ball away -- despite the fact he had a receiver open in the end zone.

The Jets took over and ran out the clock. But for the upset factor -- and the Jets beating the Colts was a sports upset unequaled until the U.S. hockey team beat the Russians in "Miracle on Ice" in the 1980 Winter Olympics -- Super Bowl III would have gone down as just another fairly dull Super Bowl.

But the Jets were huge underdogs and Namath's prediction came true, elevating him from a cocky loudmouth to a folk hero. Even today, Broadway Joe remains the purest distillation of a certain kind of modern masculinity -- a guy a certain sort of guy grew up wanting to be. An almost exact contemporary of Mick Jagger, Namath is better understood as one of the last in the Rat Pack vein (Dean Martin in shoulder pads) rather than a counterculture figure. His inclusion on Richard Nixon's infamous "enemies list" stands as yet another indication of the paranoid tone deafness of that time.

Namath, whose stats look very ordinary when measured against modern standards, was an avatar of pain, the tough man who wasn't afraid to wear pantyhose or show off his typing skills in an ad for Olivetti. His considerable significance as a football player -- he was better than some remember, though the stat sheets would only peg him as a better-than-average fantasy league acquisition -- was dwarfed by his contribution to the way we wanted to live. Namath's style was his substance, from his heavy-lidded grin to the Elvisian slur he picked up while playing for Bear Bryant at Alabama. And, like Elvis, he was a white boy who could carry off black style, another Trojan Horse through which soul and hip were smuggled into the living room of Mr. and Mrs. America.

Never overtly political, Namath was to football what Che Guevara was to radical leftist politics of the times -- an intimation of glamour in an essentially nasty business. Like the tone-deaf bongo player James Dean, Namath was a pure rock 'n' roller, never mind that his personal taste ran to 5th Dimension and Herb Alpert.

...

You probably don't need to be told Cam Newton is the 26-year-old quarterback of the Carolina Panthers, and that he represents what may be a new paradigm for the position. He is a remarkable athlete of spectacular size and gifts. He probably could play any position on the field. He is just coming off a remarkable season for which he is almost certain to be named the league's MVP.

He's also brash and black, a product of a post-rock 'n' roll culture. Not Elvis Presley, but Kanye West. He indulges in on-field celebrations that offend the sensibilities of "old school" fans. Newton is very comfortable playing like he's the biggest, fastest and strongest kid on the schoolyard. He doesn't mind if you know he's good. He knows that some hate him. He's OK with that.

In some ways Newton is a lot like Barack Obama. If you're looking, you can find plenty of reasons to dislike him. You don't have to cite his blackness as one of them.

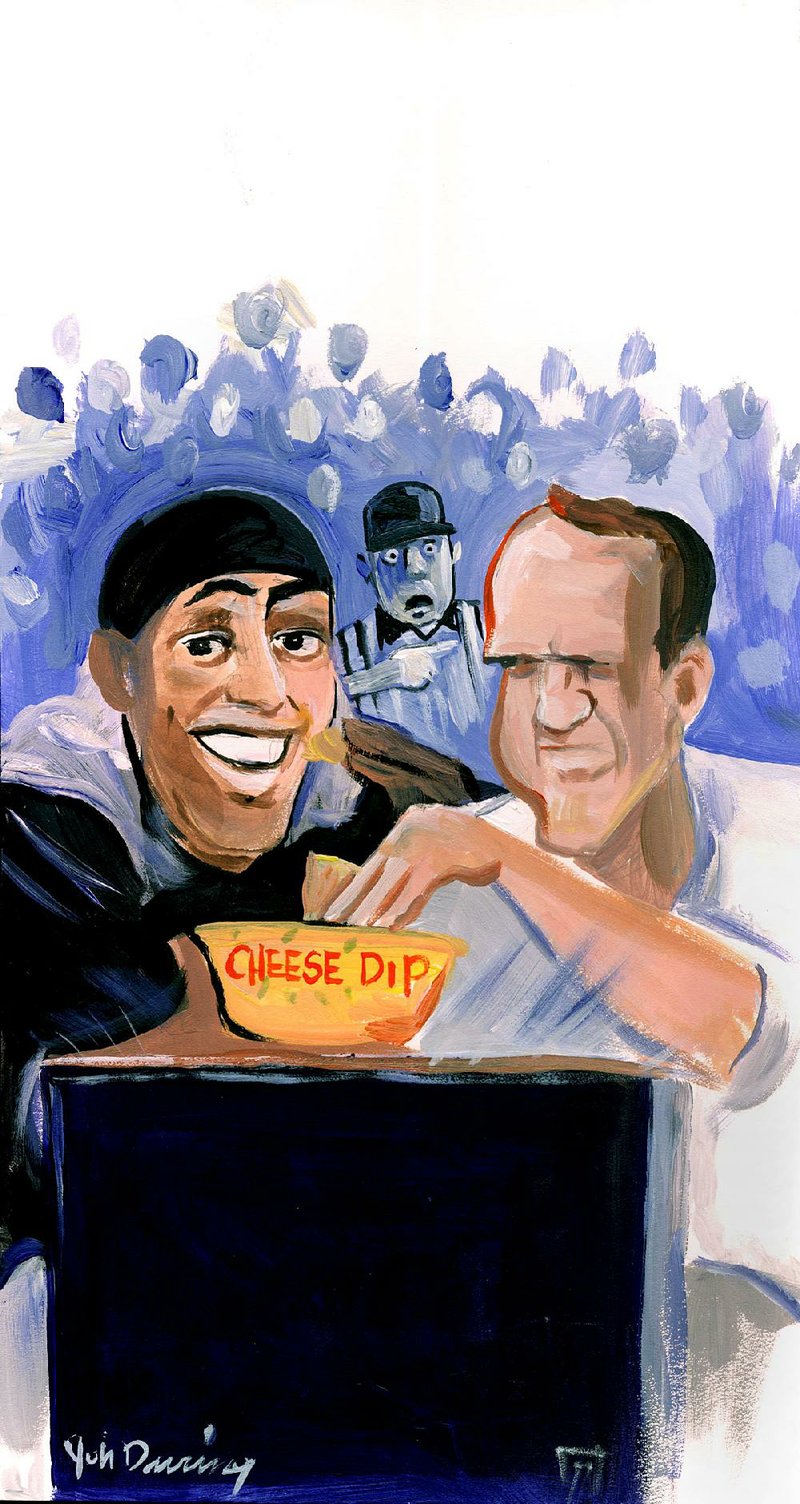

On the other hand, Manning is the legendary quarterback of the Denver Broncos, a 39-year-old who will likely be playing the final game of his career. Just a few weeks ago Manning, who'd been injured and missed games earlier in the year, was relegated to backup quarterback status. But somehow, the old Sheriff has arrived here in the year's biggest game, despite the obvious erosion of his skills. Manning can no longer throw the ball as far or with the pace he could once muster -- now, the story line is, he has to beat you with his brain.

This is all just lazy sportswriter gasbaggery. It's not Newton versus Manning -- those two men will never be on the field at the same time. While Manning has a reputation as a cerebral quarterback (some would say genius and posit him as the best thinker ever at the position), Newton's obviously got a good processor on his shoulders too. There's a method in Newton's play, and one of the reasons he was so good this year is that he mastered the traditional techniques of passing from the pocket and leading by example. While Manning might be relatively old, stiff and banged up -- he's had four surgeries on his neck due to a herniated disc, including a cervical vertebral fusion that has left him without feeling in his fingertips -- he's still plenty athletic, plenty tough.

Submitted for your approval: Newton is Namath. Manning is Unitas. Super Bowl 50 could be like Super Bowl III, a game that proves ultimately more interesting for the way it reflects our changing culture than what happens on the field.

You don't have to care about the game. You just can't avoid its implications. This is football's country.

Email:

pmartin@arkansasonline.com

Style on 02/07/2016