"I find the films that are the most interesting are the ones that deal with characters and character development, not ones that show pretty landscapes," says Roger Deakins from his home in Los Angeles.

This quote comes not from an actor or a director of small, intimate dramas. The British-born Deakins is actually a 13-time Oscar nominee for his work as a cinematographer, lighting the breathtaking scenery in films like Skyfall, Kundun and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford.

He's also lighted some of the biggest stars in the business such as Leonardo Di Caprio and Arkansas' Billy Bob Thornton and supervised the lighting and camera crews for Angelina Jolie when she stepped behind the camera for Unbroken. He has earned a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society of Cinematographers in 2011, and, like guitarist Eric Clapton, has even been called "God" by his fans. That's not bad for a fellow who has been denied a little gold man despite decades of stellar work.

When reminded of how he has been mistaken for a deity, Deakins laughs and admits, "That's funny. I did a Clapton video once -- really: 'Forever Man.'"

Throughout the 30 minute conversation, Deakins says he may not be due for the idolatry that's due to Jesus or even Clapton.

"It's flattering. I just like doing my job. All that stuff doesn't affect me. Oscars and all that stuff is a lot of hype and hoopla. What I like is just doing the job."

THE FRATERNAL BOND

For 26 years, Deakins has been a regular contributor to Joel and Ethan Coen's films, serving as director of photography for each one of their movies since 1991's Barton Fink, with the exception of Inside Llewyn Davis and Burn After Reading.

Deakins has also regularly worked with director Edward Zwick (Courage Under Fire, The Siege), Sam Mendes (Skyfall, Jarhead) and Denis Villeneuve (Prisoners, Sicario).

While he's loyal to the Coens, he's also eager to share his enthusiasm for working with Villeneuve. (Deakins' latest Academy Award nomination is for Sicario, now available on Blu-ray and DVD.)

"[W]orking with a director like Denis Villeneuve, it's a great creative experience for me. He's pushing to put the audience into this world through the eyes of one character," he says.

"You have that relationship, and you keep yourself free to work with them, and it's kind of hard to work with anybody else. I've obviously turned down quite a bit of work because I was working with them. Frankly, when I was working on Hail, Caesar!, I couldn't work with Sam again (on Spectre). You can't do it all, you know. I'm very lucky."

OLD TIME RELIGION

He's back with the brothers again for Hail, Caesar!, which opened last week. The film stars Josh Brolin as real-life studio fixer Eddie Mannix, who has the unenviable task of covering up Hollywood stars' misbehavior while searching for a kidnapped actor (George Clooney) playing the lead in a Biblical epic, Hail, Caesar! Deakins and the Coens use 1950s storytelling tools to match the period in which their fictional story is set. The movie features comical tributes to Gene Kelly and Esther Williams as well as glossy sword and sandals dramas.

"We were using painted backings, which people don't use much now. One of the backings we had in the Roman courtyard sequence was actually a backing that was painted for Ben-Hur, that we found in a prop rental house," Deakins recalls. "It wasn't a complete tribute to the films of the '50s, so we didn't want to go too far, really."

If the Coens and Deakins are reticent to make too much fun of TCM fare, it's because they know how hard those movies were to make. While Channing Tatum's dancing skills are well established, even he had to put in a lot of effort to replicate the agile footsteps of Donald O'Connor.

"The dancers and Channing spent three weeks or something rehearsing that number. Joel and Ethan and myself went in on a weekend and played it through in small sections and mapped out what shots we were going to shoot well in advance of actually shooting it. I probably spent a week before lighting the set to work in the lighting cues. It's a small scene in the film, but it took a lot of planning and a lot of work just for that," Deakins says.

"The whole wide shot where you see the camera crane as though it was shooting the dance number, that had to be choreographed with what we were shooting as if it were that camera."

DYING OF THE LIGHT

Deakins has shown a remarkable facility for working in 35mm film and digital. That said, Hail, Caesar! marks his return to analog cinema after a long absence.

"True Grit was the last one I did, and that was a while ago [2010, to be exact]," he says. "It would be great to think that film would still be there as a creative choice. Joel and Ethan or Quentin Tarantino want to shoot film. The fact is that economically there's not been the business model for it for a couple of years.

"Basically, the studios are bankrolling Kodak to make the stock. They're guaranteeing Kodak a certain amount of money to make the film stock, but they're not doing that with the labs, so the whole infrastructure is just gradually fading away. Whatever you think of the arguments between film and digital, it's a fact that everything's going to go digital. There's no question, really."

A TRUER TRUE GRIT

Deakins is especially pleased with how he and the Coens were able to adapt Charles Portis' True Grit in a manner that more accurately reflects the novel and the setting in 19th-century Fort Smith. The 1969 adaptation starring John Wayne may have featured Natural State alumnus Glen Campbell, but the admittedly gorgeous Colorado is a bizarre substitute for the actual locale. New Mexico and Texas worked better.

"It's a pity we couldn't actually shoot there, Deakins laments. "They went back to the original material. In a way, I feel it's a real pity that the John Wayne version even exists because the Coens' movie is much more true to the original material, and frankly, I think it's a much better film, but it always will be in the shadow with the John Wayne movie."

Like the Duke's version, the newer version has stunning camerawork, and the curious won't have to guess how Deakins achieves his images.

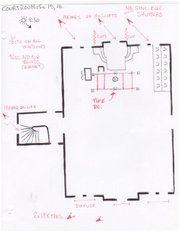

His website (rogerdeakins.com) is a subscriber-only site, but membership is free. In one recent entry he not only explains how he and his cohorts lit a scene where Jeff Bridges, as Rooster Cogburn, humiliates a hostile attorney in a Fort Smith courtroom. He even includes a chart he drew that explains how the lights were set up.

He recalls, "I've had that site for quite a long time. Students and other people were asking me to put up lighting diagrams, and actually I didn't do that until about six months ago. I started thinking, 'Why not?'

"Really, I think the way I learned my craft was not through copying anybody. That's how I would like to think other people learn their craft, you know, not by copying what I do. I put up lighting diagrams with that proviso. It's technically interesting, but you shouldn't be trying to mimic it. There's no point really."

MovieStyle on 02/12/2016